Covers system administration tasks like maintaining, monitoring and customizing an initially installed system.

- About This Guide

- I Common Tasks

- II Booting a Linux System

- III System

- 15 32-Bit and 64-Bit Applications in a 64-Bit System Environment

- 16

journalctl: Query thesystemdJournal - 17 Basic Networking

- 17.1 IP Addresses and Routing

- 17.2 IPv6—The Next Generation Internet

- 17.3 Name Resolution

- 17.4 Configuring a Network Connection with YaST

- 17.5 NetworkManager

- 17.6 Configuring a Network Connection Manually

- 17.7 Basic Router Setup

- 17.8 Setting Up Bonding Devices

- 17.9 Setting Up Team Devices for Network Teaming

- 17.10 Software-Defined Networking with Open vSwitch

- 18 Printer Operation

- 19 The X Window System

- 20 Accessing File Systems with FUSE

- 21 Managing Kernel Modules

- 22 Dynamic Kernel Device Management with

udev- 22.1 The

/devDirectory - 22.2 Kernel

ueventsandudev - 22.3 Drivers, Kernel Modules and Devices

- 22.4 Booting and Initial Device Setup

- 22.5 Monitoring the Running

udevDaemon - 22.6 Influencing Kernel Device Event Handling with

udevRules - 22.7 Persistent Device Naming

- 22.8 Files used by

udev - 22.9 For More Information

- 22.1 The

- 23 Live Patching the Linux Kernel Using kGraft

- 24 Special System Features

- 25 Persistent Memory

- IV Services

- 26 Time Synchronization with NTP

- 27 The Domain Name System

- 28 DHCP

- 29 Sharing File Systems with NFS

- 30 Samba

- 31 On-Demand Mounting with Autofs

- 32 SLP

- 33 The Apache HTTP Server

- 33.1 Quick Start

- 33.2 Configuring Apache

- 33.3 Starting and Stopping Apache

- 33.4 Installing, Activating, and Configuring Modules

- 33.5 Enabling CGI Scripts

- 33.6 Setting Up a Secure Web Server with SSL

- 33.7 Running Multiple Apache Instances on the Same Server

- 33.8 Avoiding Security Problems

- 33.9 Troubleshooting

- 33.10 For More Information

- 34 Setting Up an FTP Server with YaST

- 35 The Proxy Server Squid

- 35.1 Some Facts about Proxy Caches

- 35.2 System Requirements

- 35.3 Basic Usage of Squid

- 35.4 The YaST Squid Module

- 35.5 The Squid Configuration File

- 35.6 Configuring a Transparent Proxy

- 35.7 Using the Squid Cache Manager CGI Interface (

cachemgr.cgi) - 35.8 squidGuard

- 35.9 Cache Report Generation with Calamaris

- 35.10 For More Information

- 36 Web Based Enterprise Management Using SFCB

- V Mobile Computers

- VI Troubleshooting

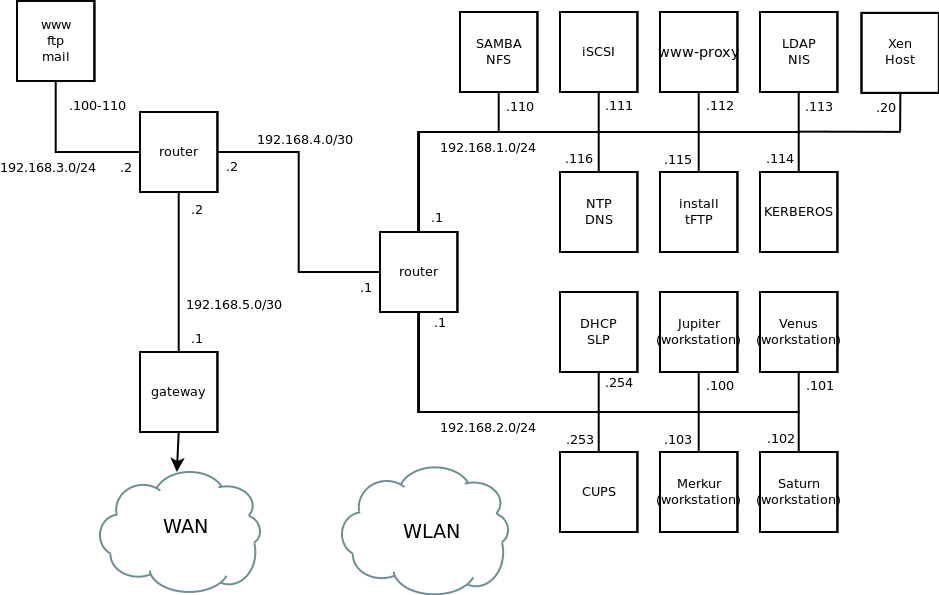

- A An Example Network

- B GNU licenses

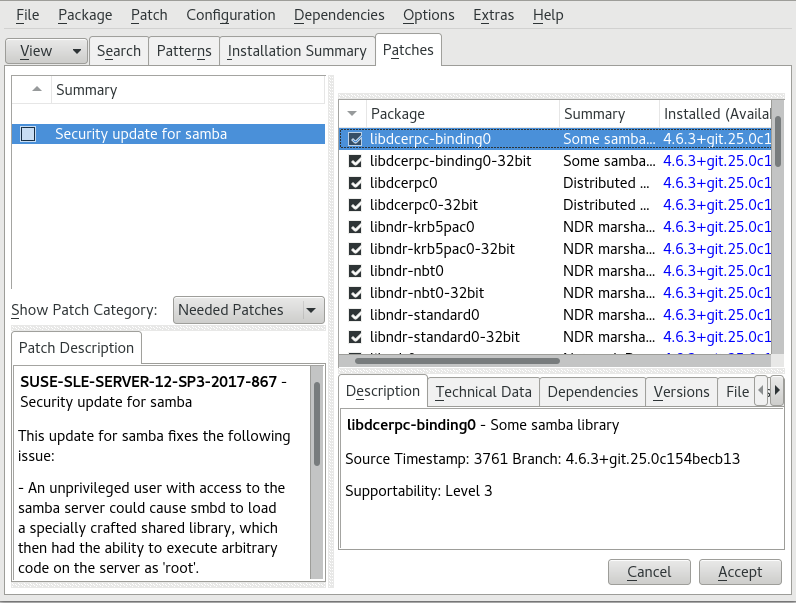

- 3.1 YaST Online Update

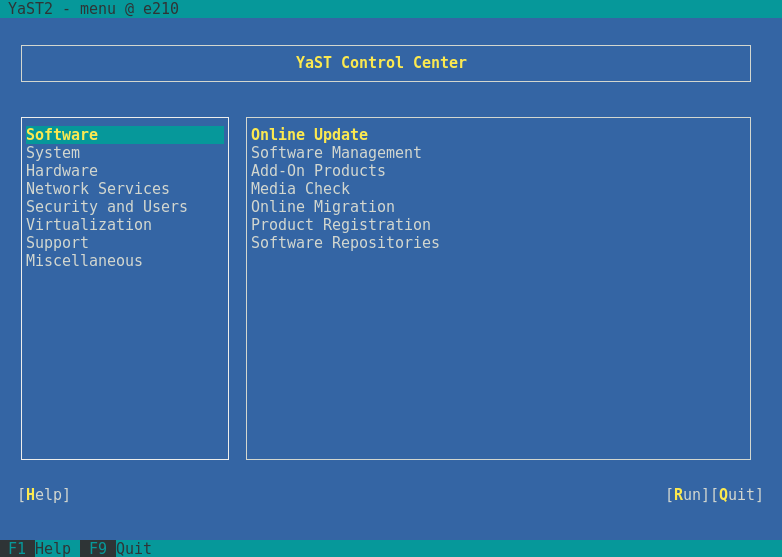

- 5.1 Main Window of YaST in Text Mode

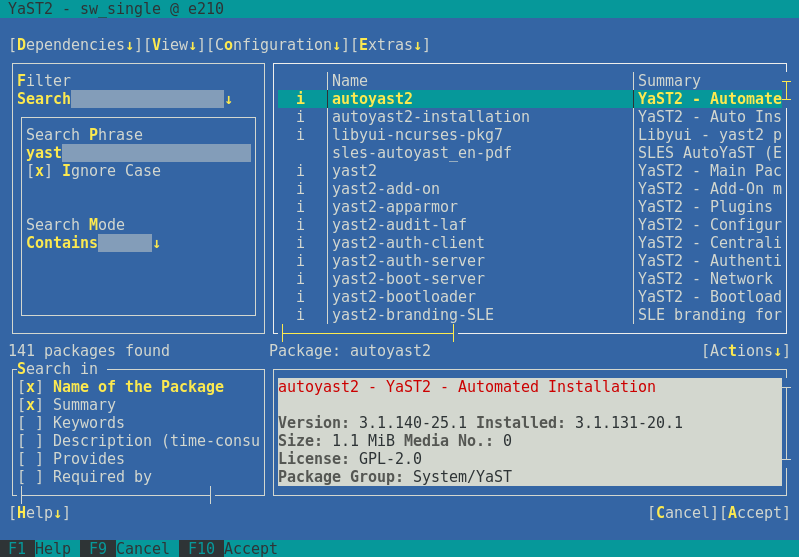

- 5.2 The Software Installation Module

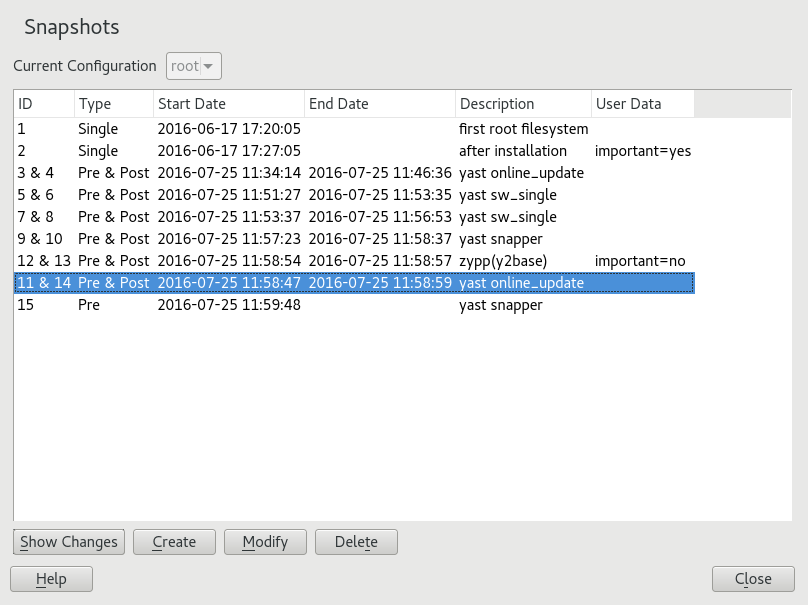

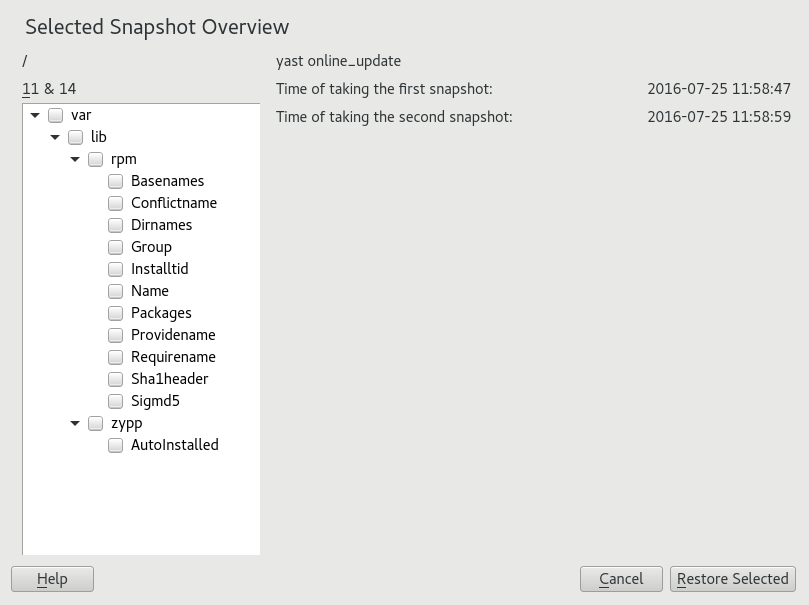

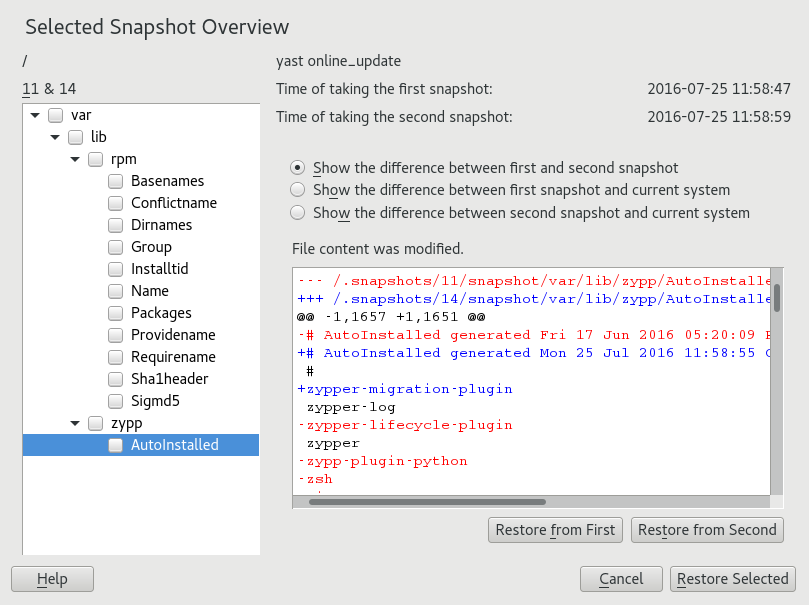

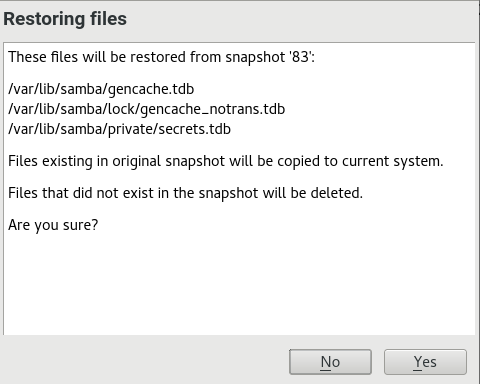

- 7.1 Boot Loader: Snapshots

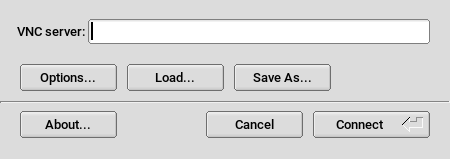

- 8.1 vncviewer

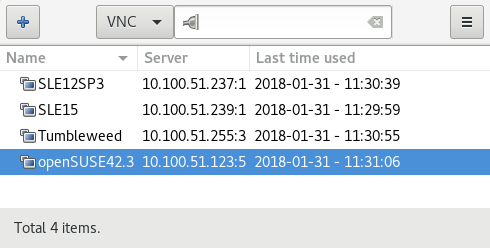

- 8.2 Remmina's Main Window

- 8.3 Remote Desktop Preference

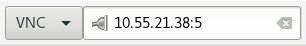

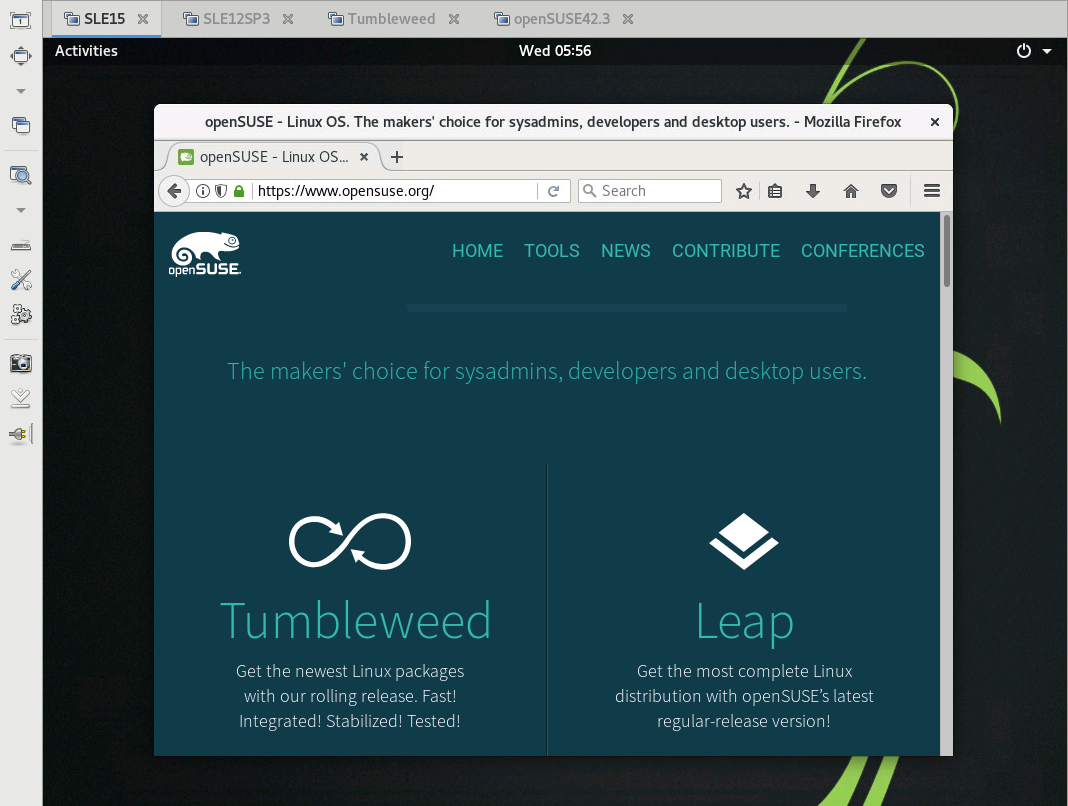

- 8.4 Quick-starting

- 8.5 Remmina Viewing SLES 15 Remote Session

- 8.6 Reading Path to the Profile File

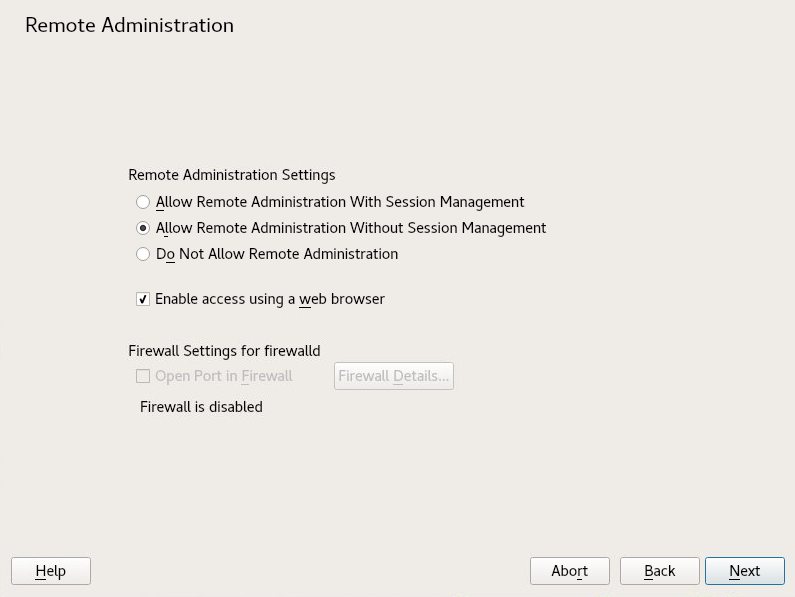

- 8.7 Remote Administration

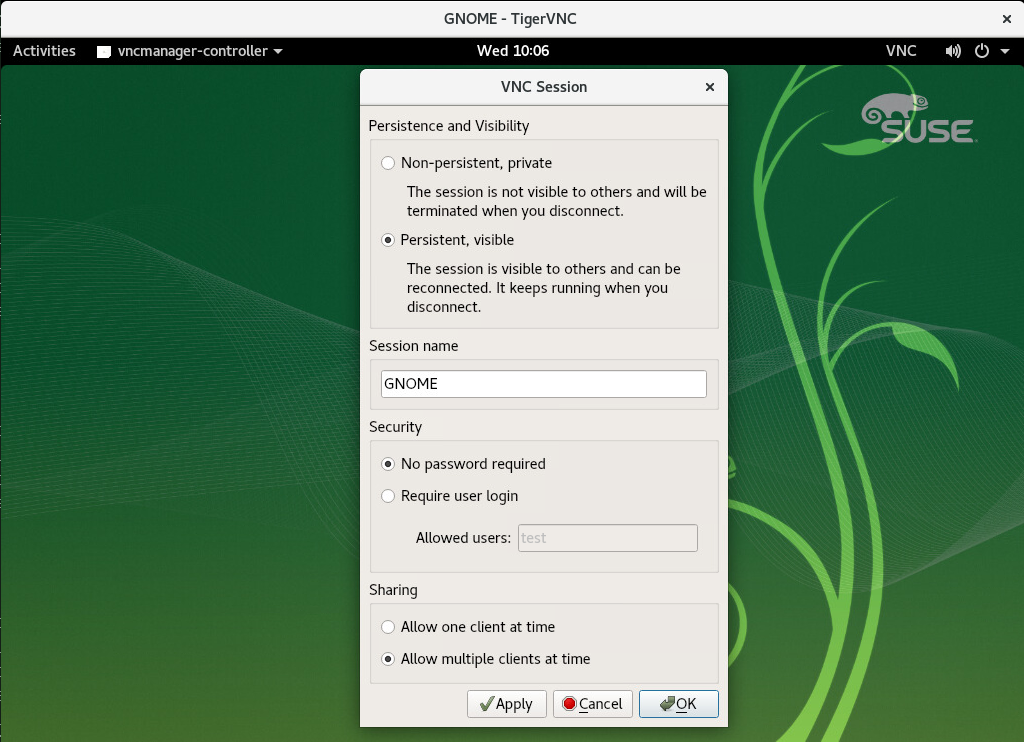

- 8.8 VNC Session Settings

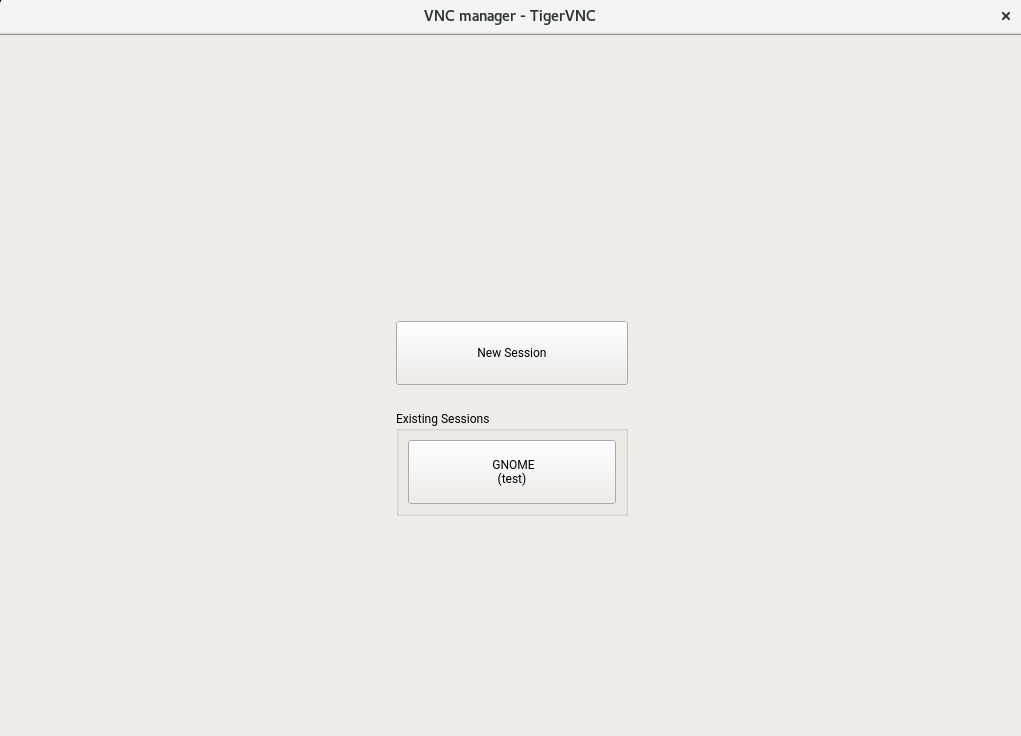

- 8.9 Joining a Persistent VNC Session

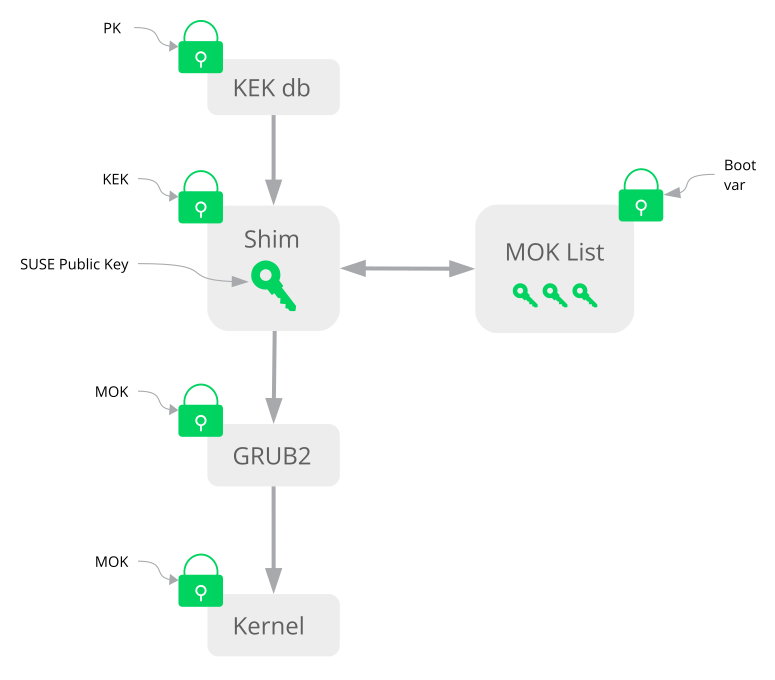

- 12.1 Secure Boot Support

- 12.2 UEFI: Secure Boot Process

- 13.1 GRUB 2 boot editor

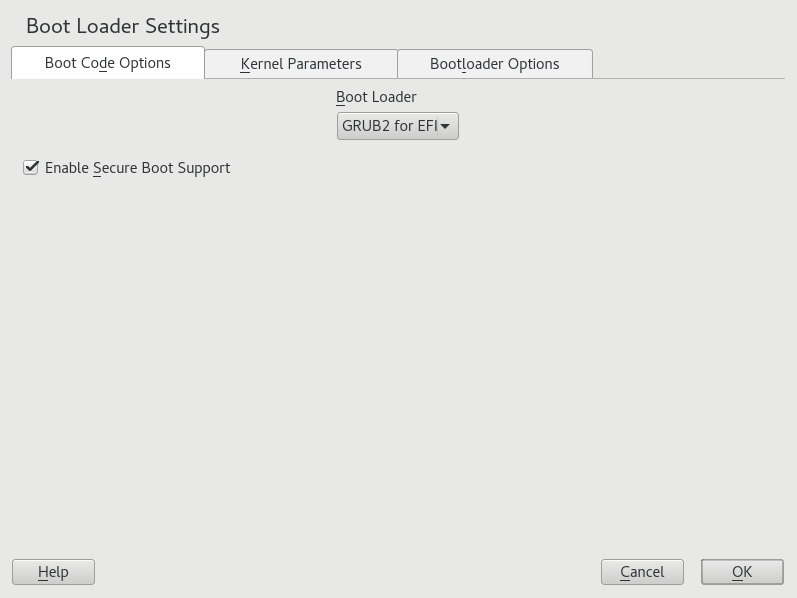

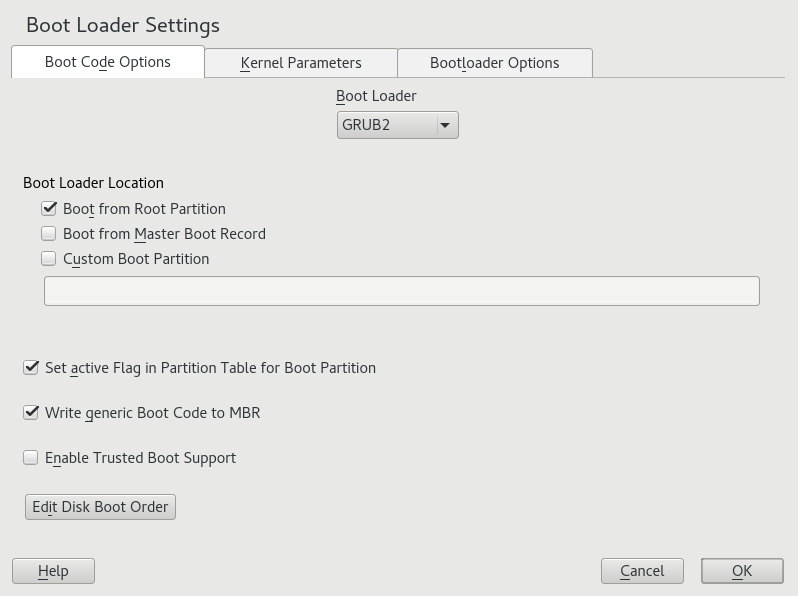

- 13.2 Boot Code Options

- 13.3 Code Options

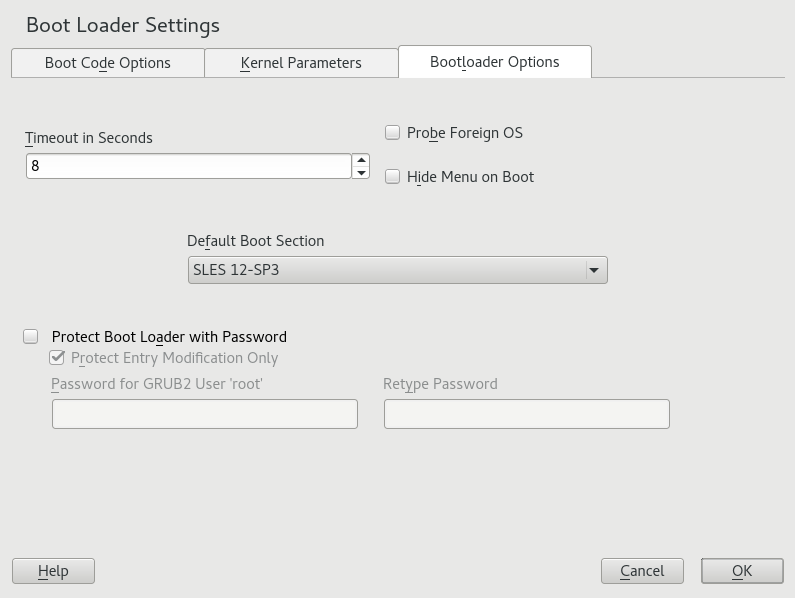

- 13.4 Boot loader Options

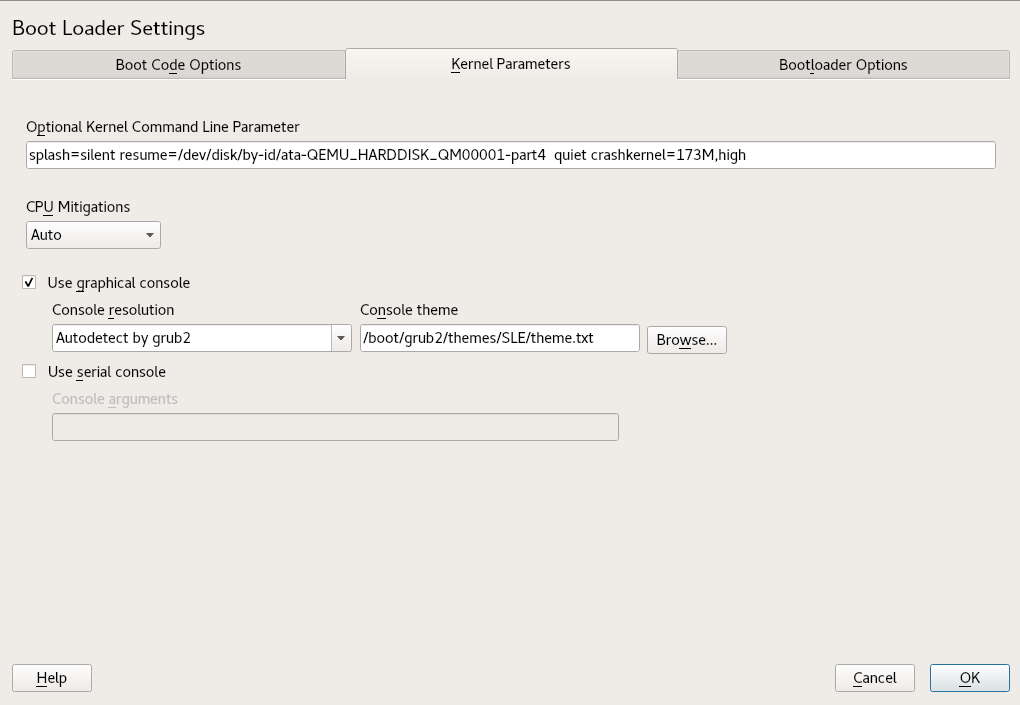

- 13.5 Kernel Parameters

- 14.1 Services Manager

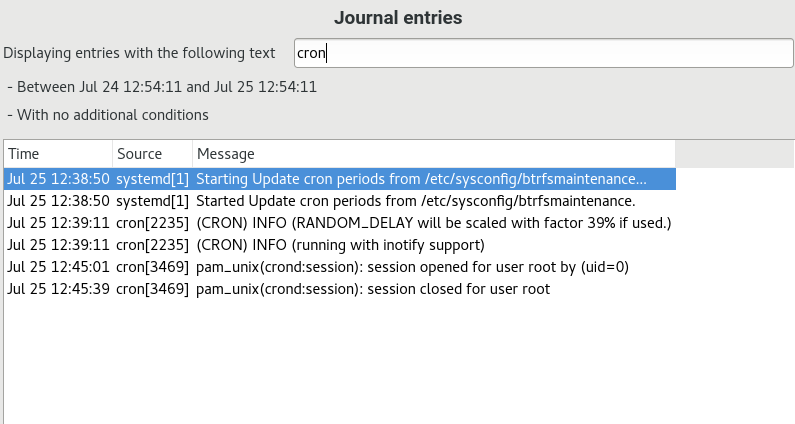

- 16.1 YaST systemd Journal

- 17.1 Simplified Layer Model for TCP/IP

- 17.2 TCP/IP Ethernet Packet

- 17.3 Configuring Network Settings

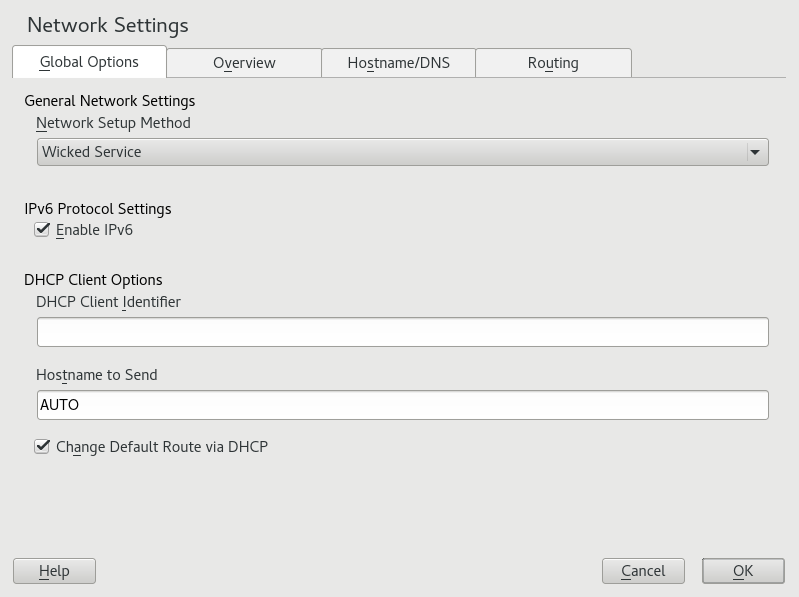

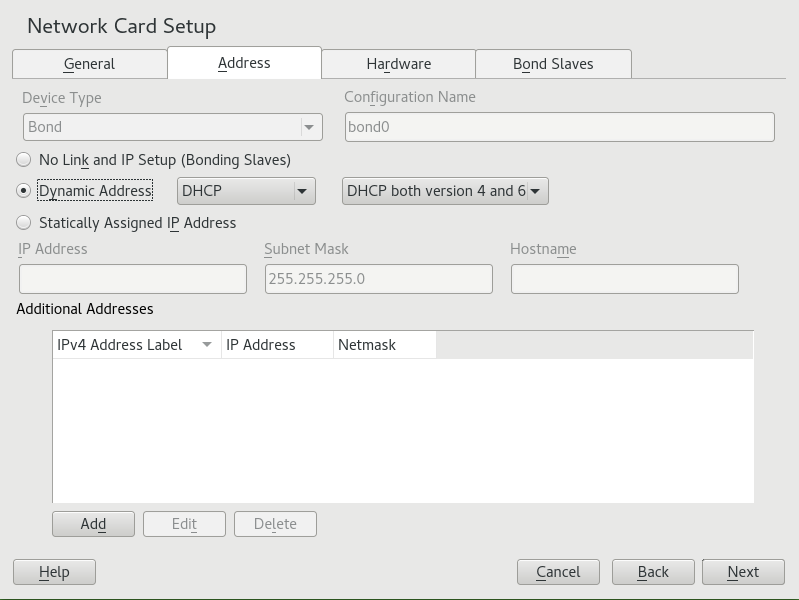

- 17.4

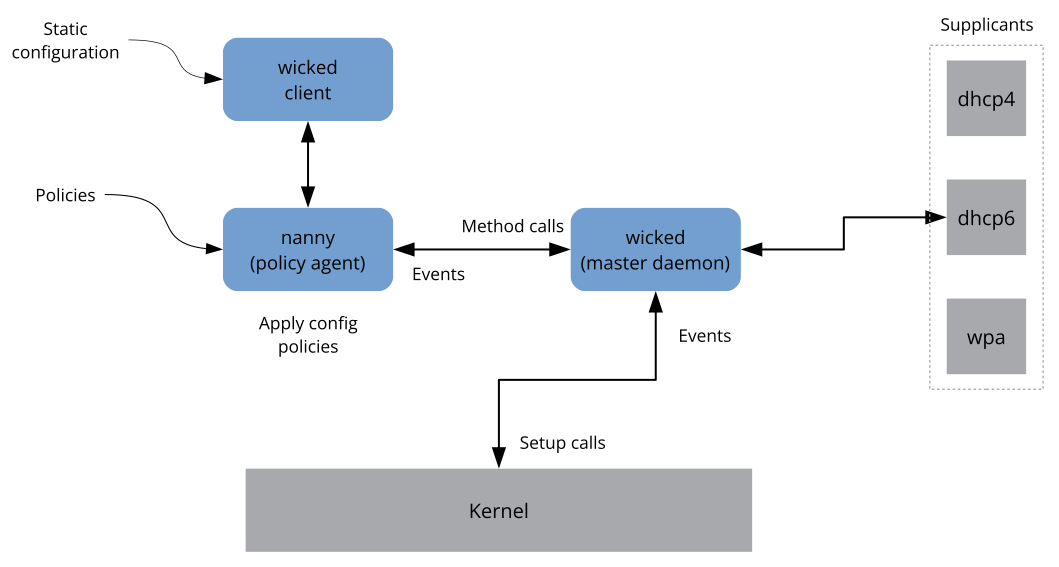

wickedarchitecture - 25.1 NVDIMM Region Layout

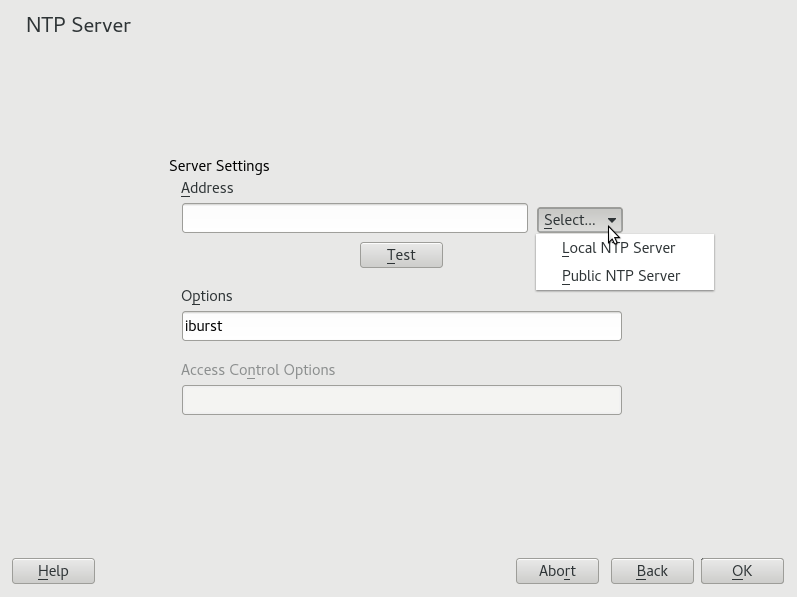

- 26.1 YaST: NTP Server

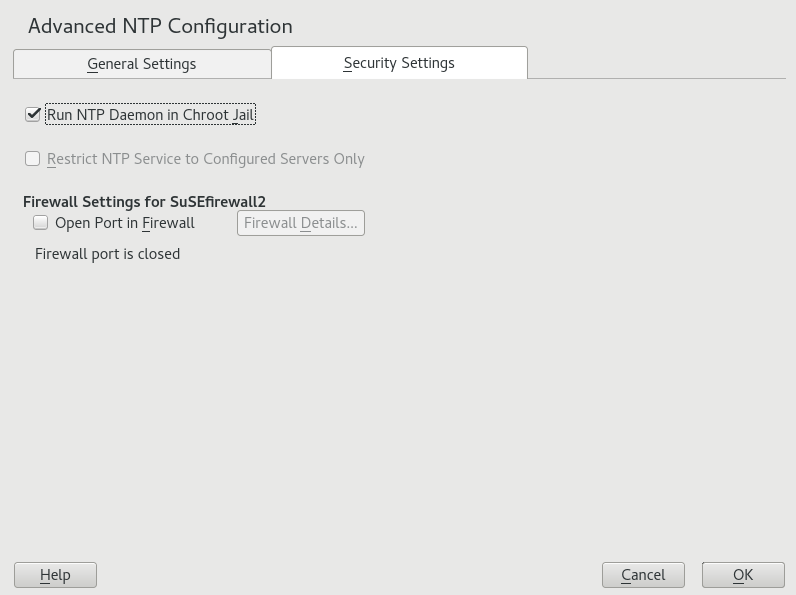

- 26.2 Advanced NTP Configuration: Security Settings

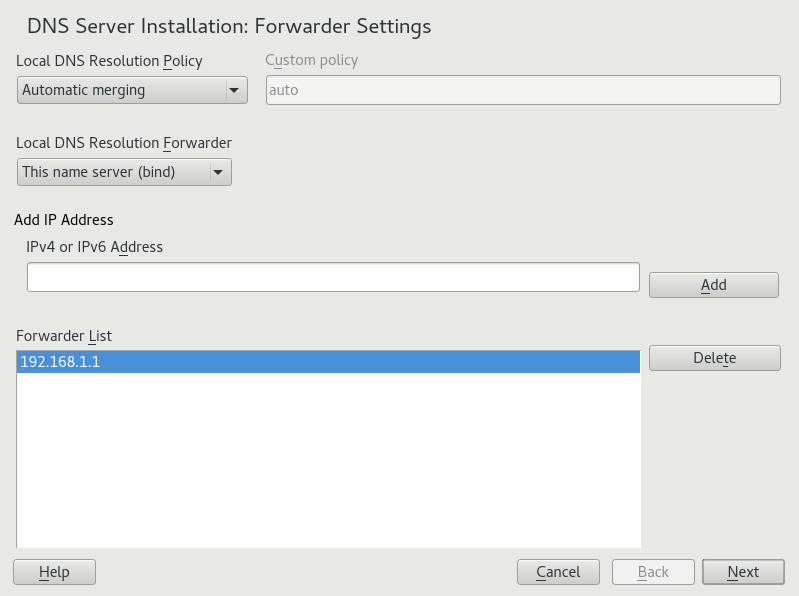

- 27.1 DNS Server Installation: Forwarder Settings

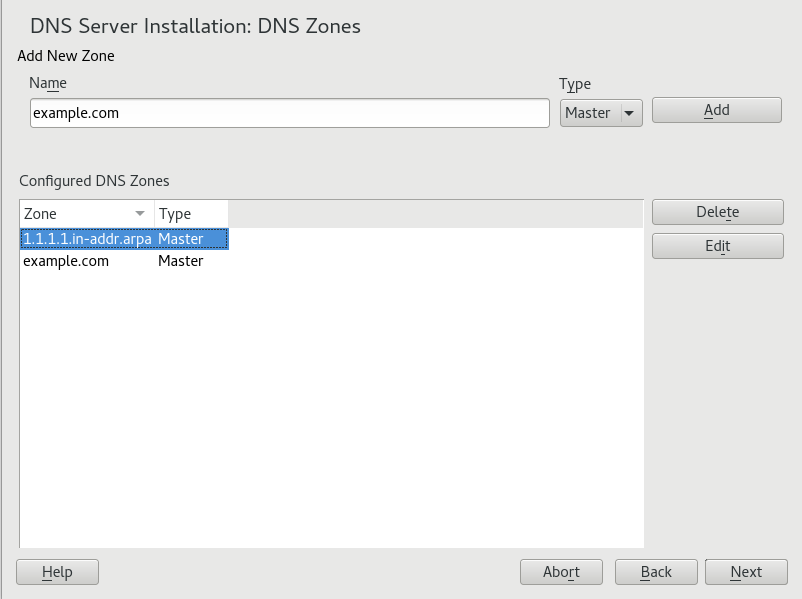

- 27.2 DNS Server Installation: DNS Zones

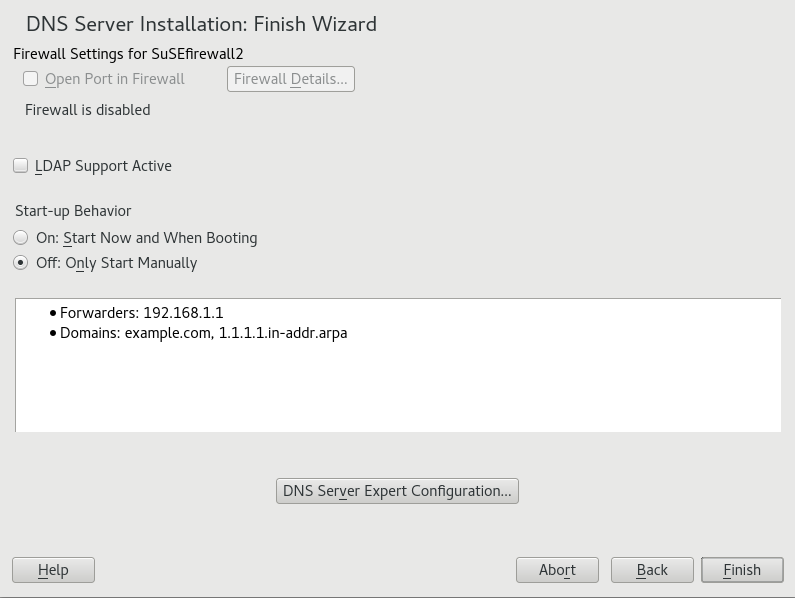

- 27.3 DNS Server Installation: Finish Wizard

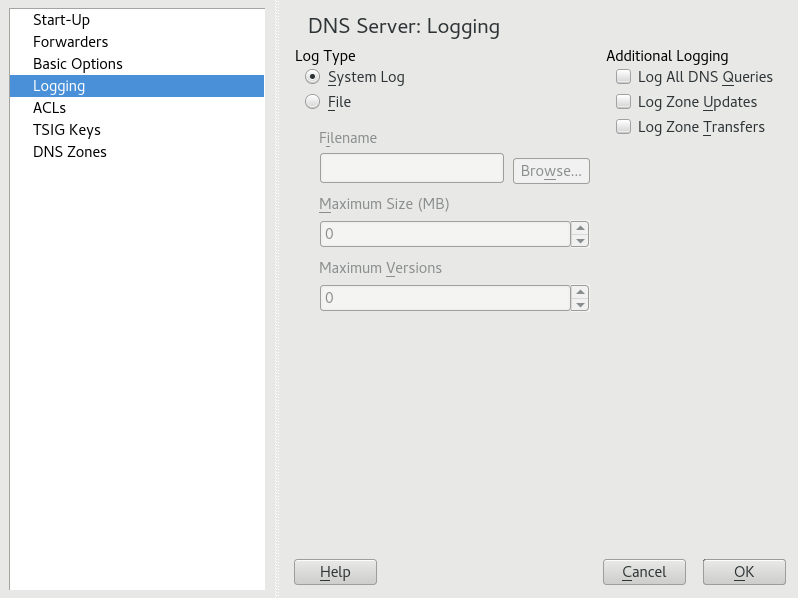

- 27.4 DNS Server: Logging

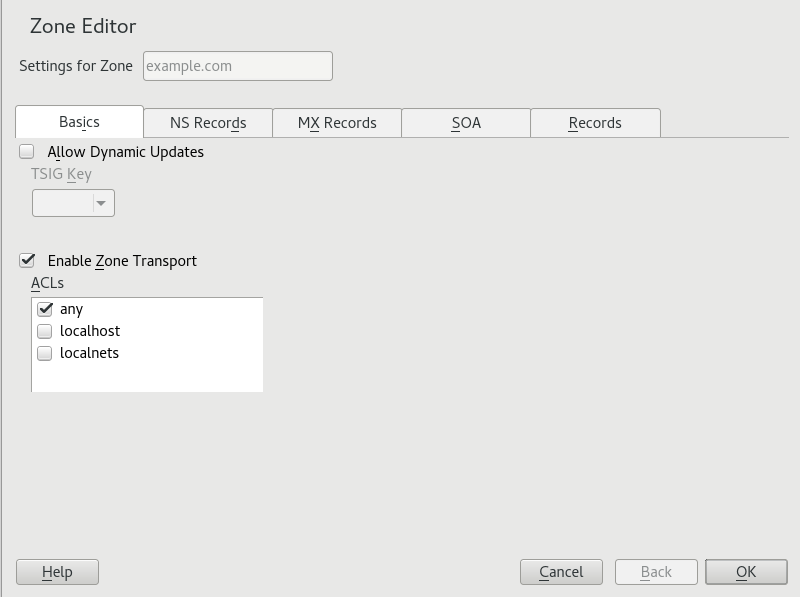

- 27.5 DNS Server: Zone Editor (Basics)

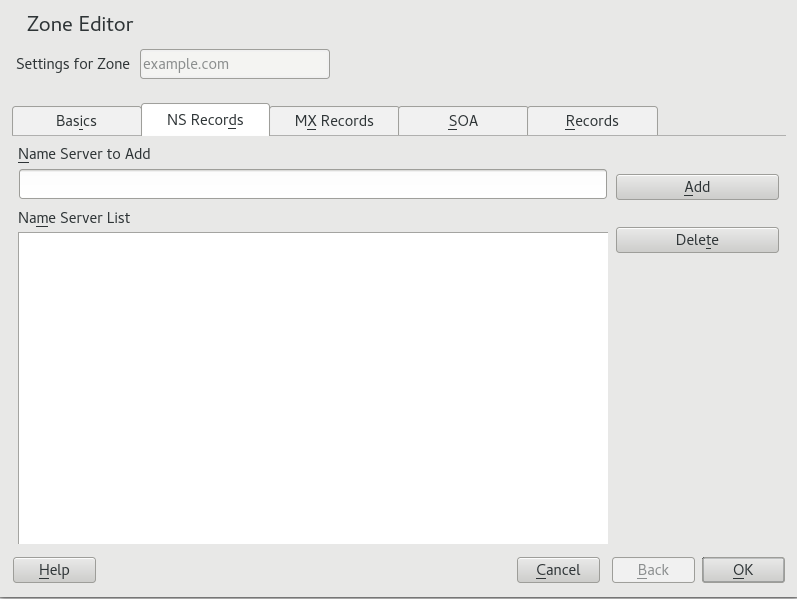

- 27.6 DNS Server: Zone Editor (NS Records)

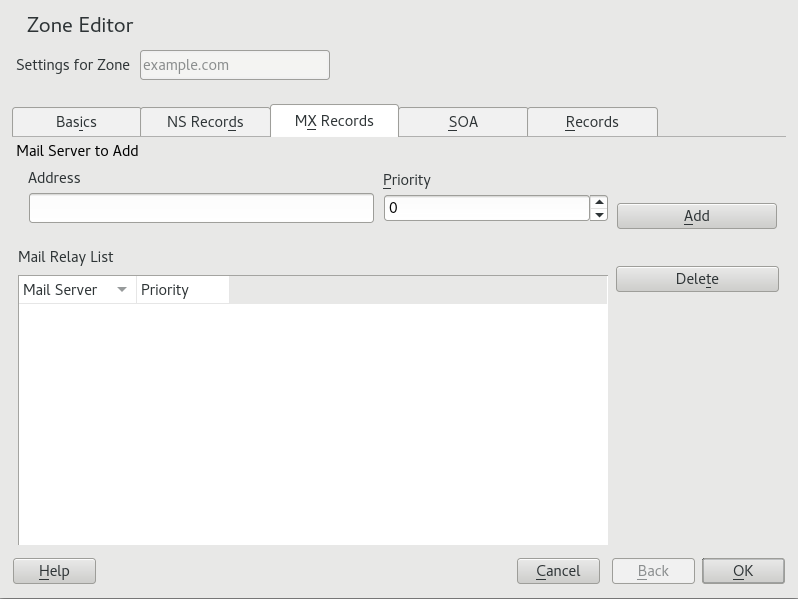

- 27.7 DNS Server: Zone Editor (MX Records)

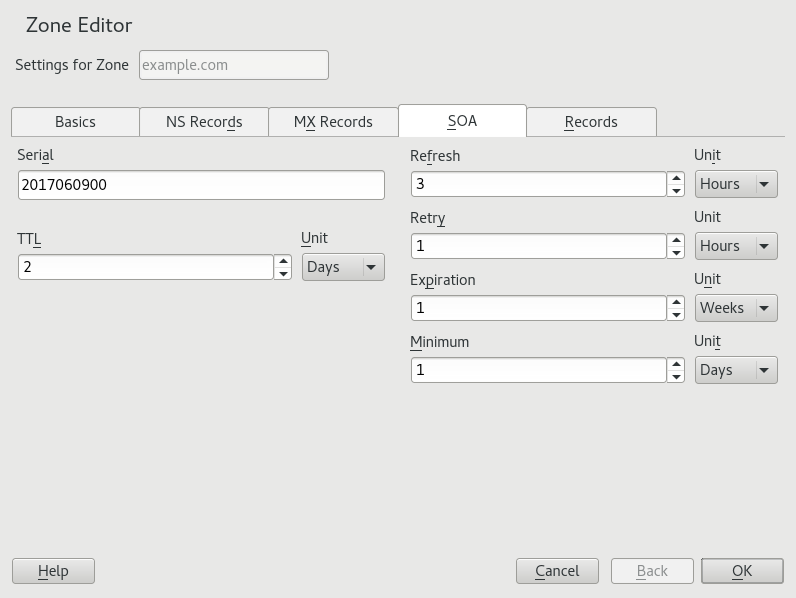

- 27.8 DNS Server: Zone Editor (SOA)

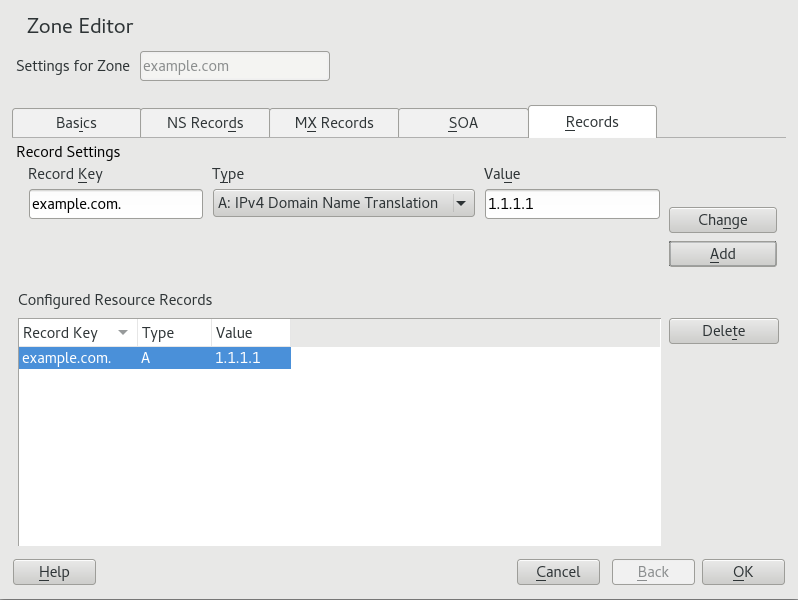

- 27.9 Adding a Record for a Master Zone

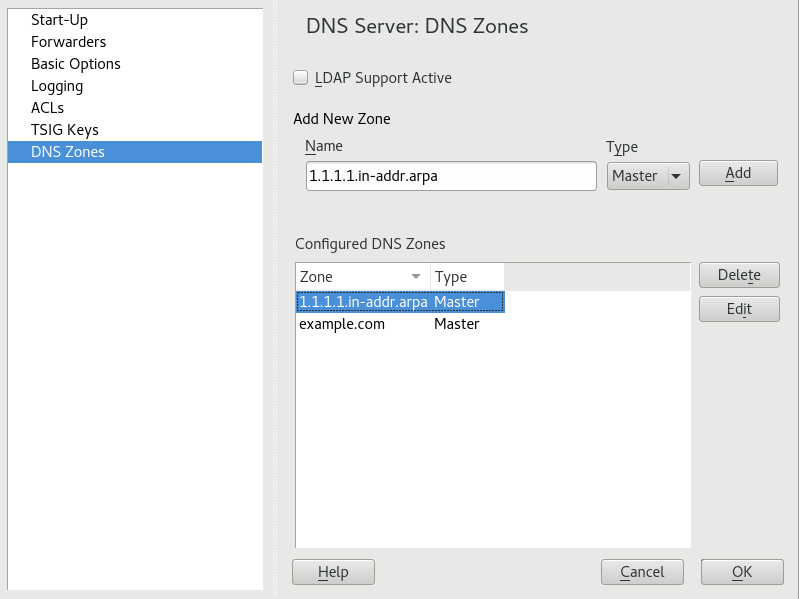

- 27.10 Adding a Reverse Zone

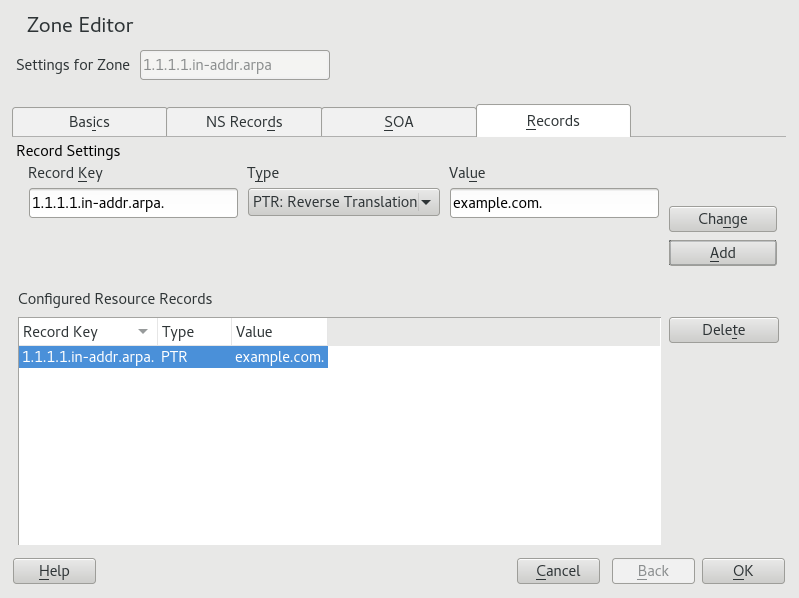

- 27.11 Adding a Reverse Record

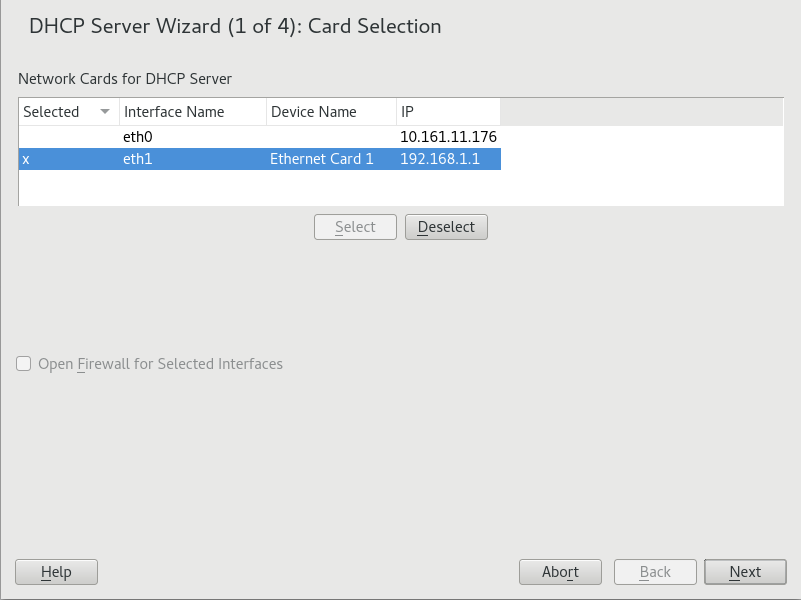

- 28.1 DHCP Server: Card Selection

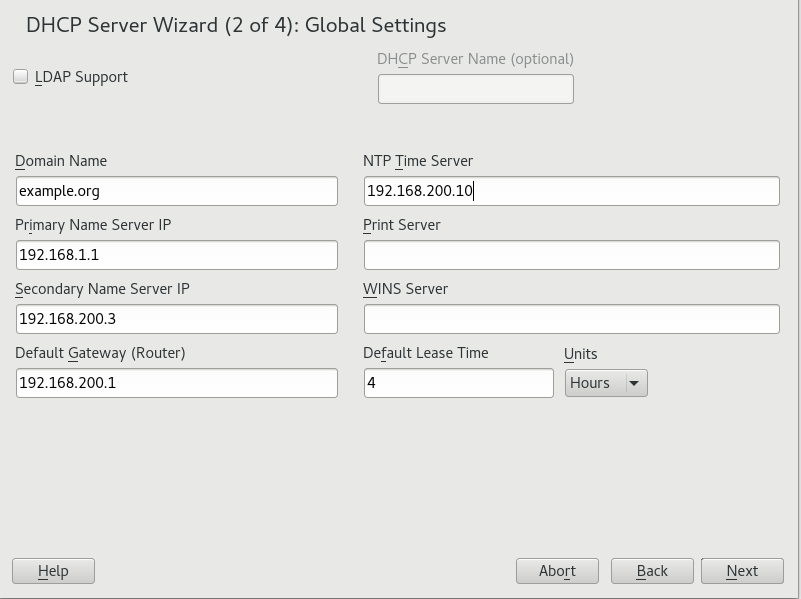

- 28.2 DHCP Server: Global Settings

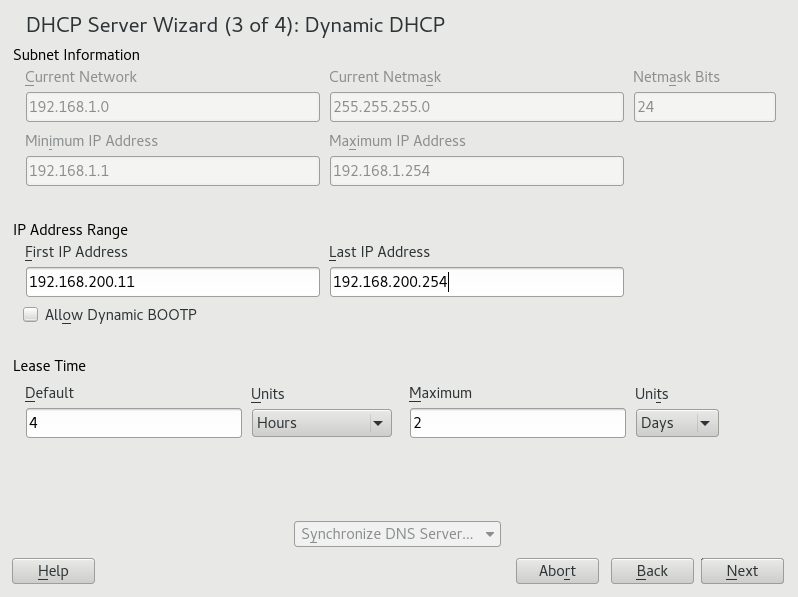

- 28.3 DHCP Server: Dynamic DHCP

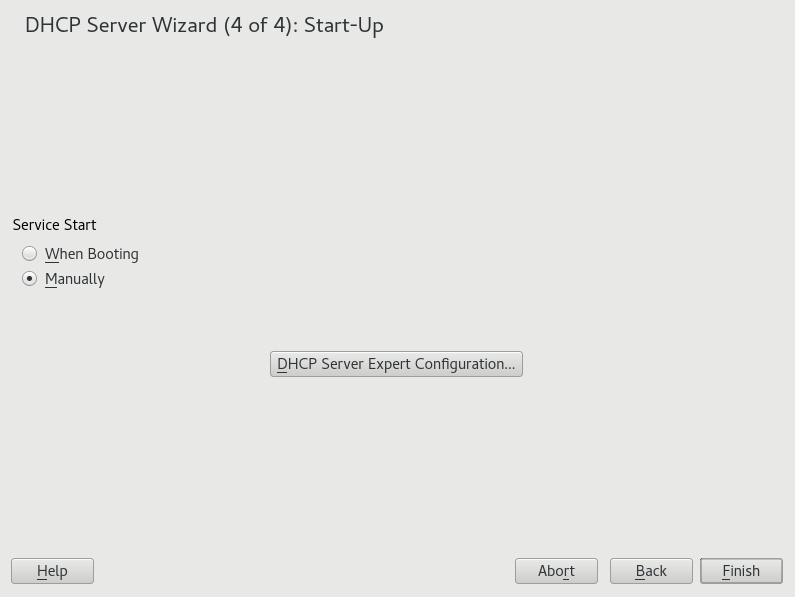

- 28.4 DHCP Server: Start-Up

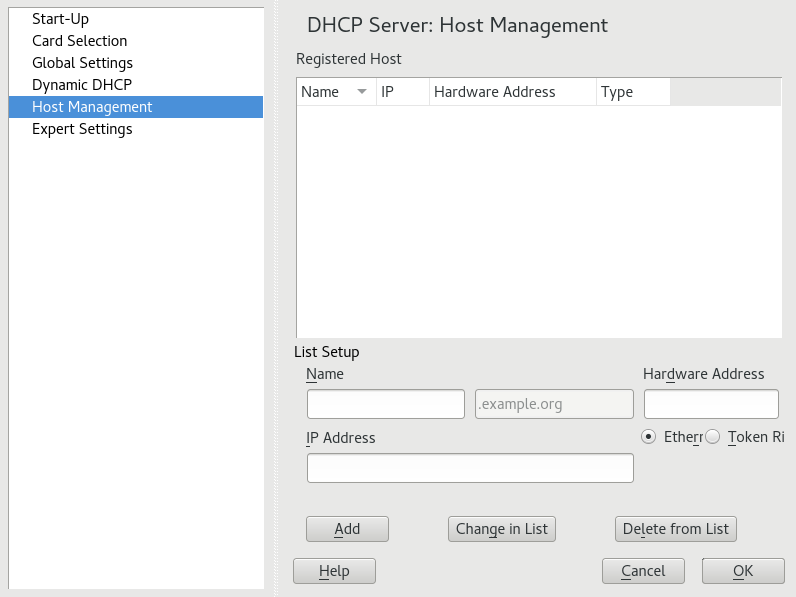

- 28.5 DHCP Server: Host Management

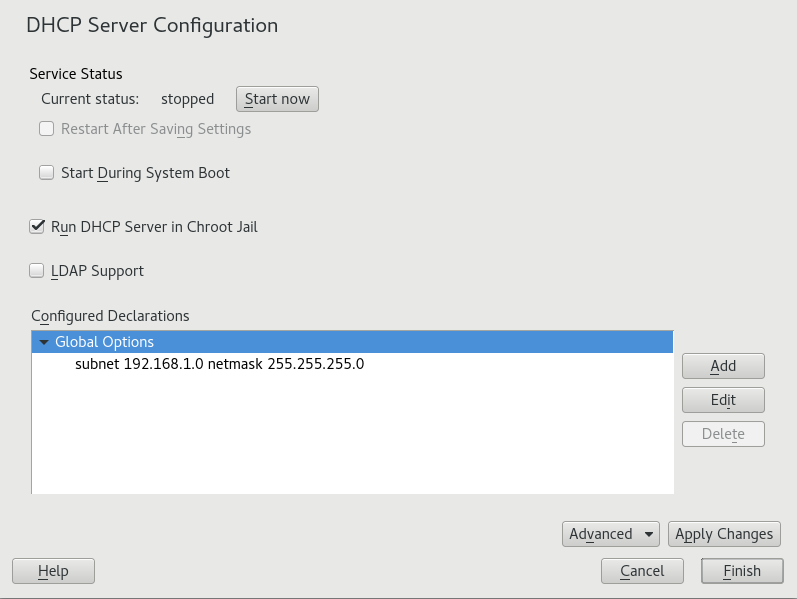

- 28.6 DHCP Server: Chroot Jail and Declarations

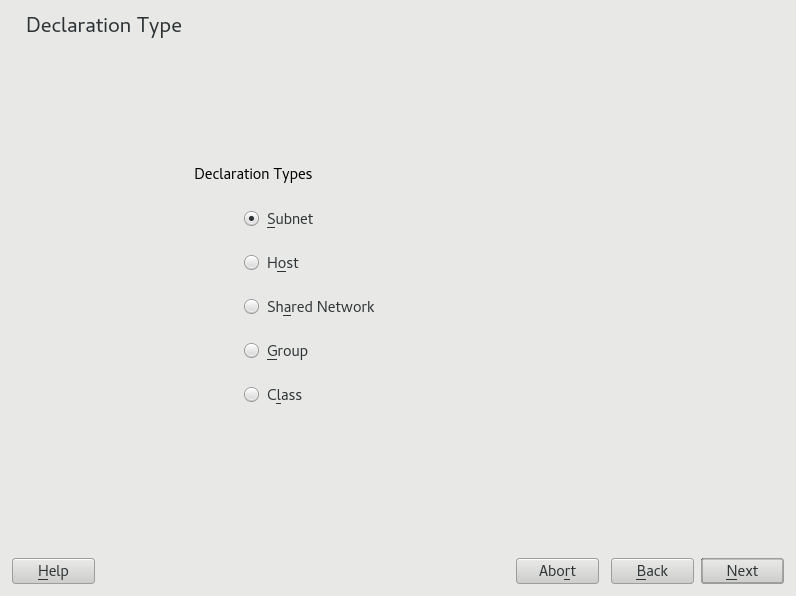

- 28.7 DHCP Server: Selecting a Declaration Type

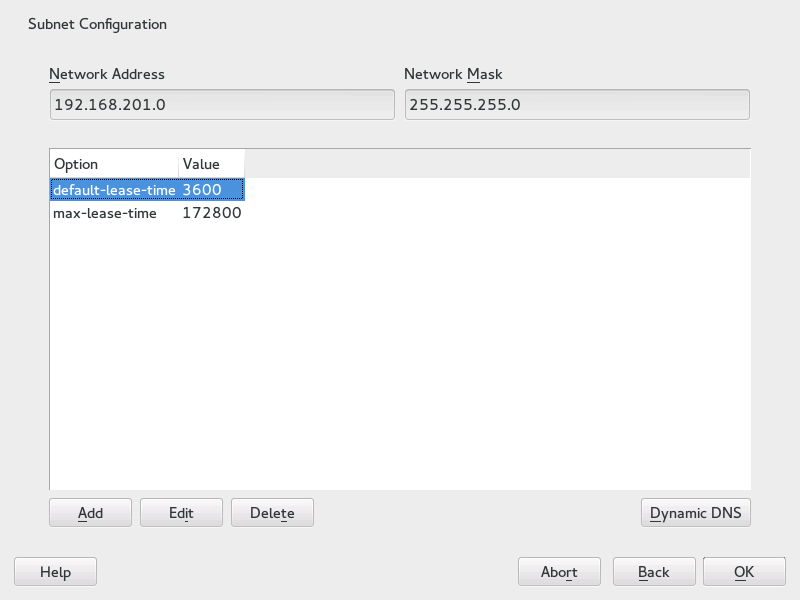

- 28.8 DHCP Server: Configuring Subnets

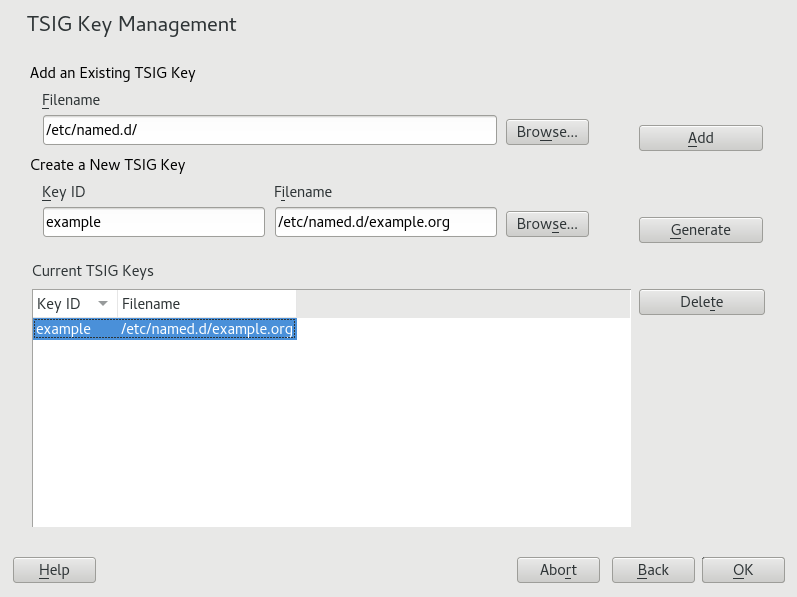

- 28.9 DHCP Server: TSIG Configuration

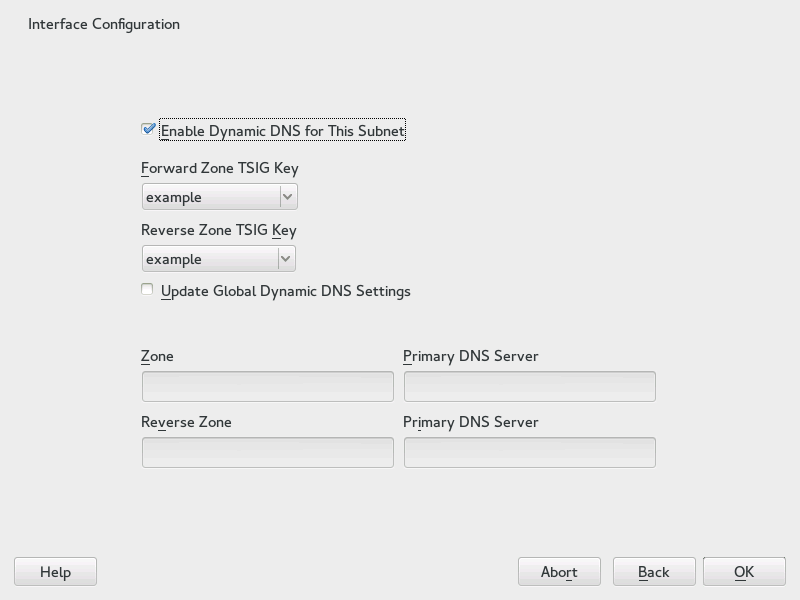

- 28.10 DHCP Server: Interface Configuration for Dynamic DNS

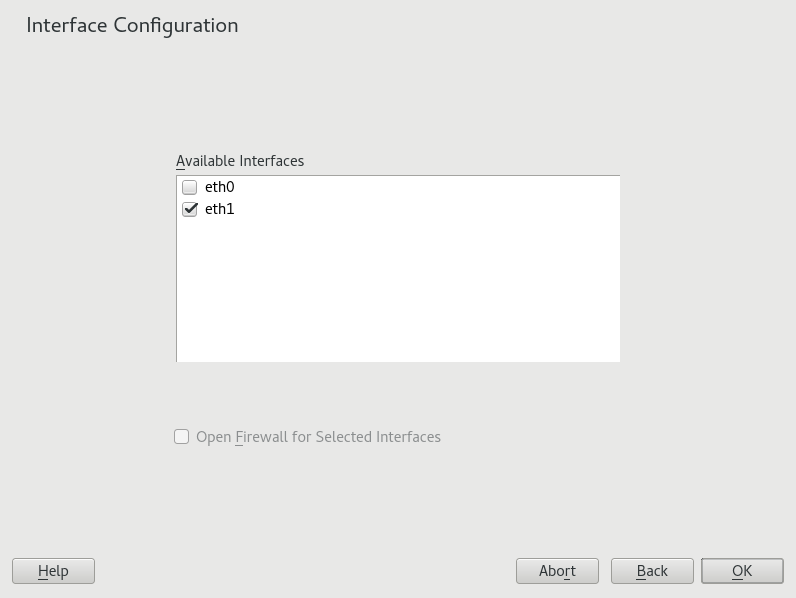

- 28.11 DHCP Server: Network Interface and Firewall

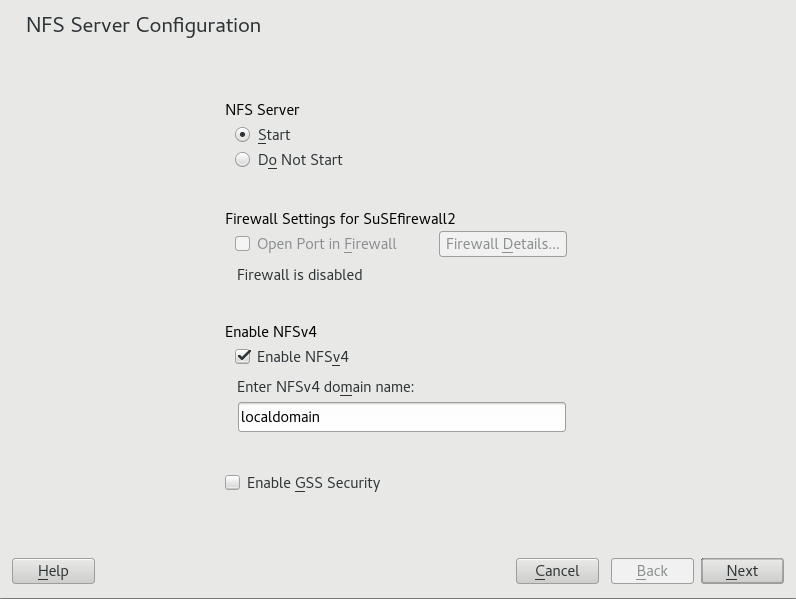

- 29.1 NFS Server Configuration Tool

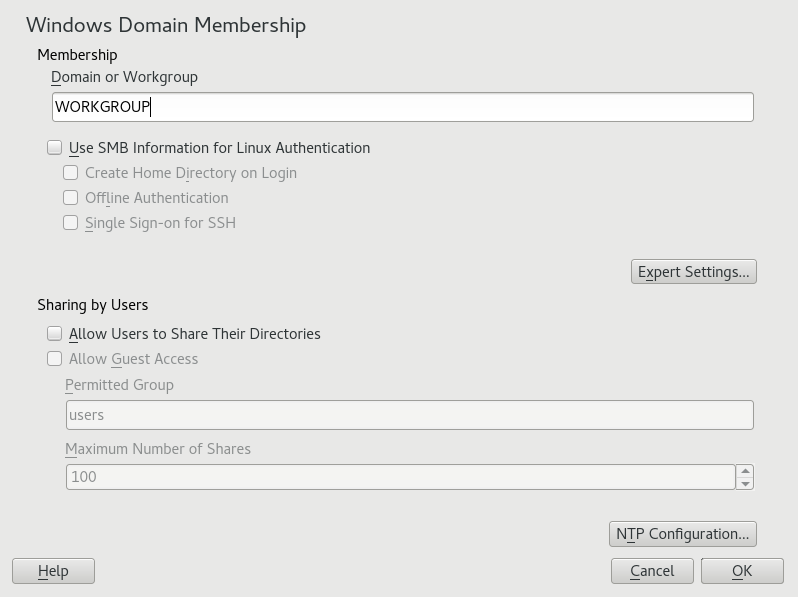

- 30.1 Determining Windows Domain Membership

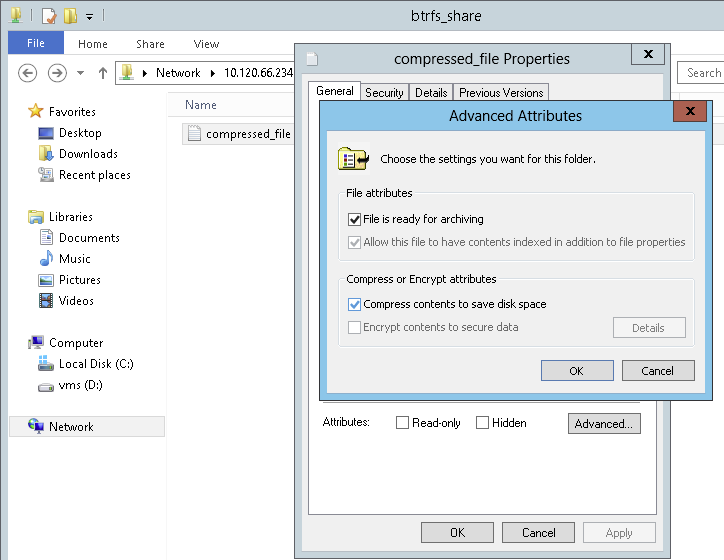

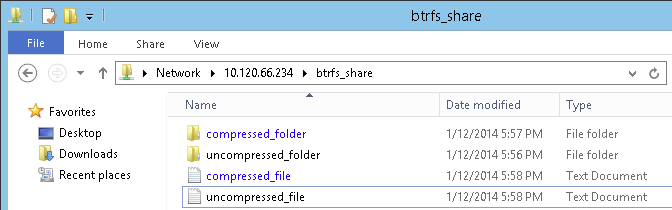

- 30.2 Windows Explorer Dialog

- 30.3 Windows Explorer Directory Listing with Compressed Files

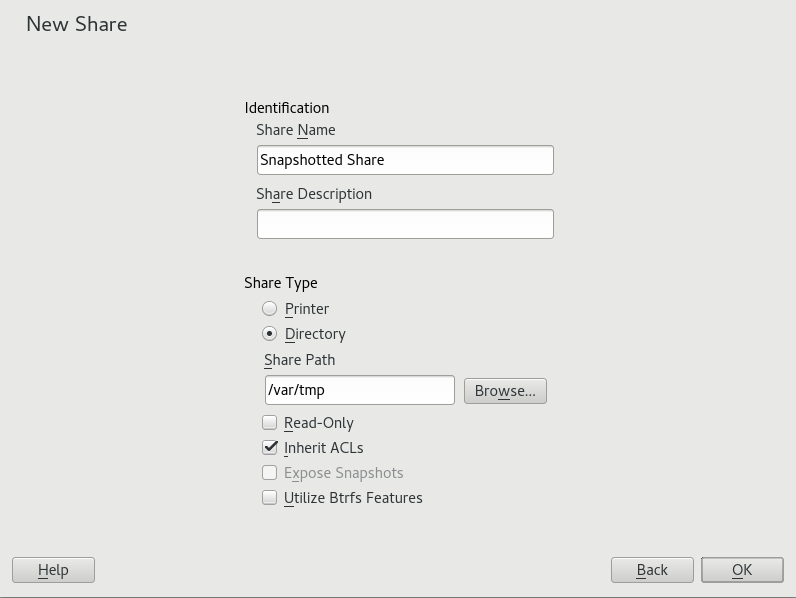

- 30.4 Adding a New Samba Share with Snapshotting Enabled

- 30.5 The tab in Windows Explorer

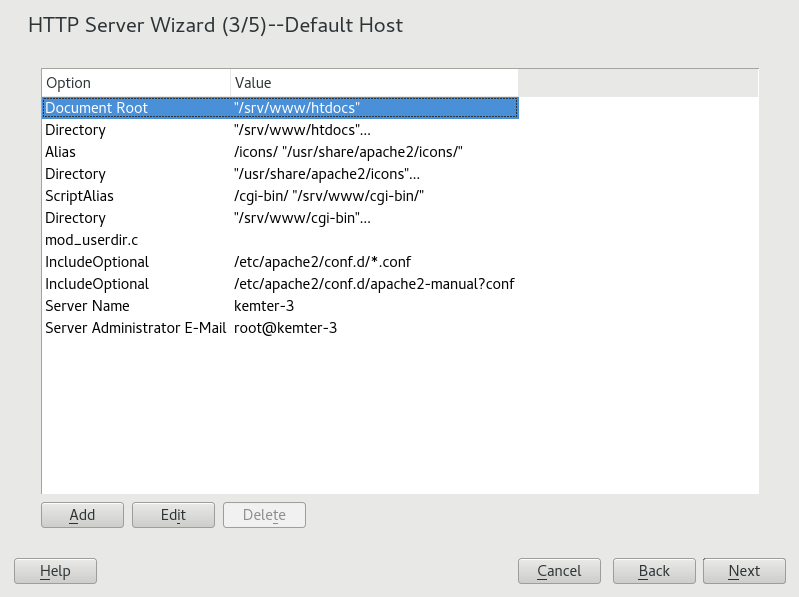

- 33.1 HTTP Server Wizard: Default Host

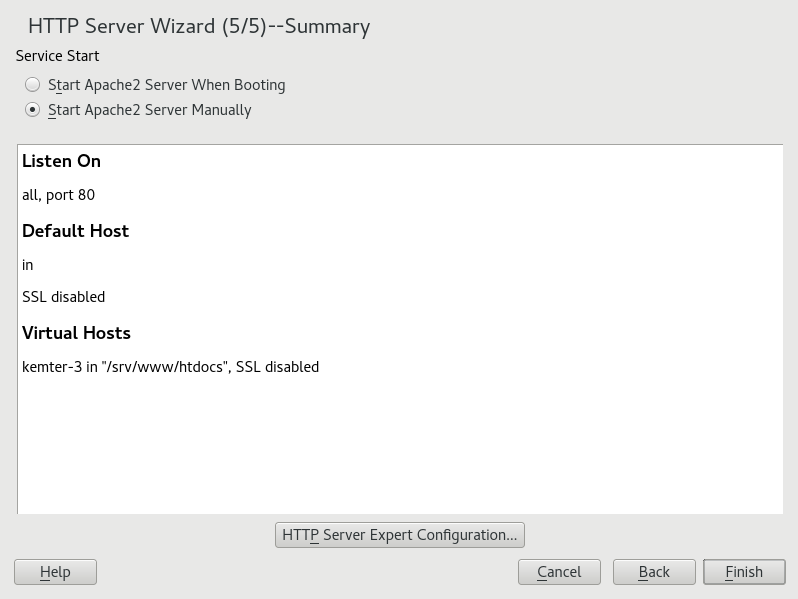

- 33.2 HTTP Server Wizard: Summary

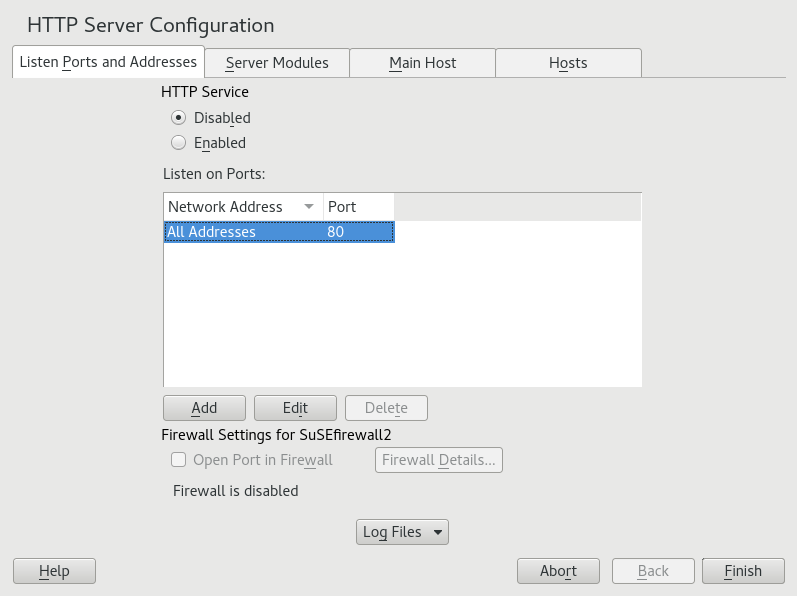

- 33.3 HTTP Server Configuration: Listen Ports and Addresses

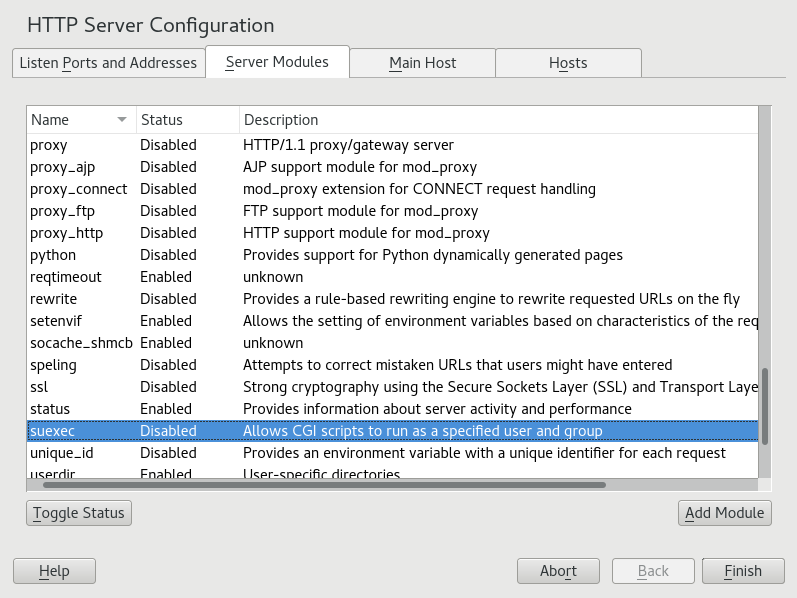

- 33.4 HTTP Server Configuration: Server Modules

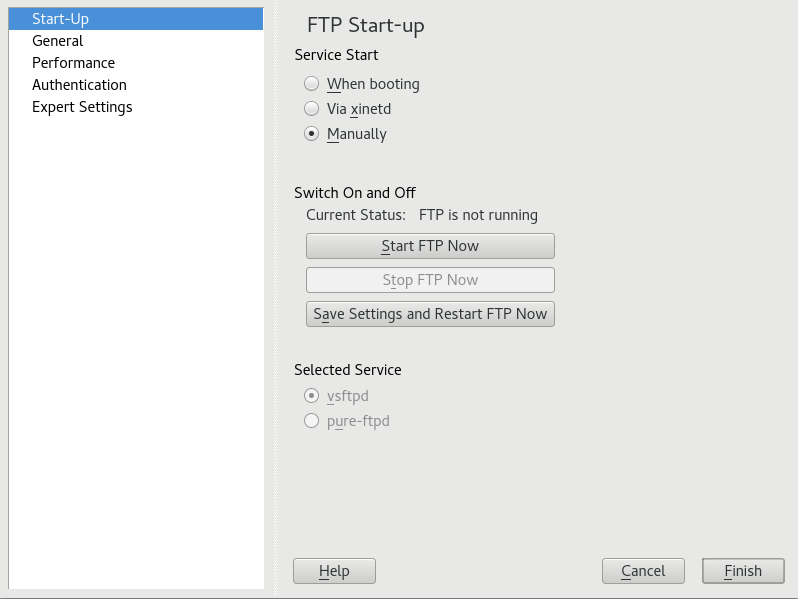

- 34.1 FTP Server Configuration — Start-Up

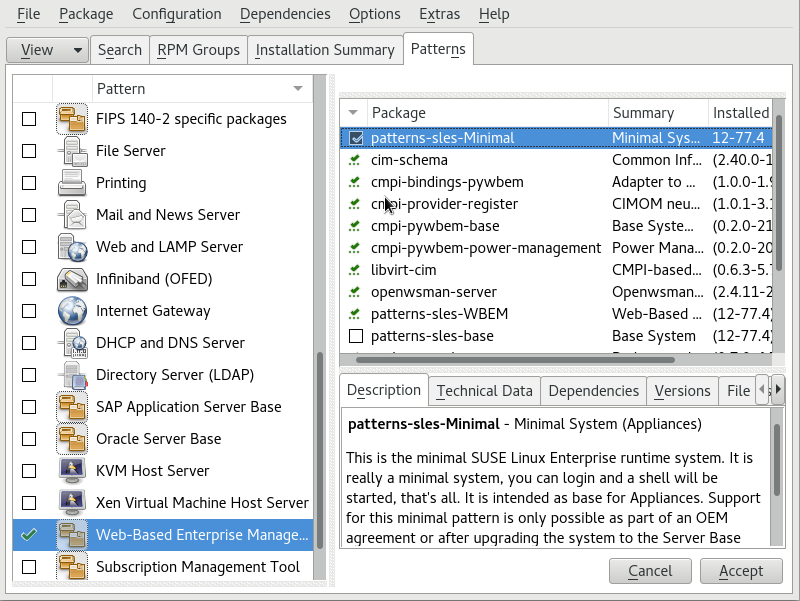

- 36.1 Package Selection for Web-Based Enterprise Management Pattern

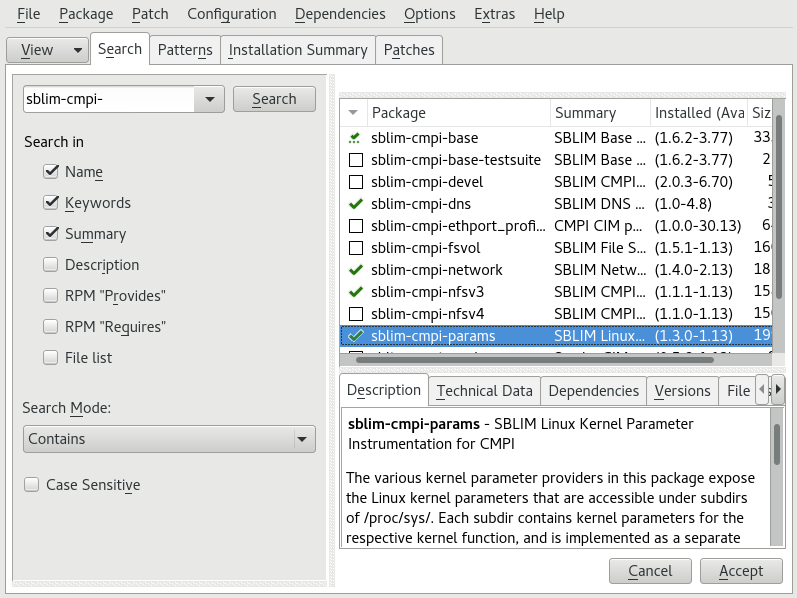

- 36.2 Package selection of additional CIM providers

- 37.1 Integrating a Mobile Computer in an Existing Environment

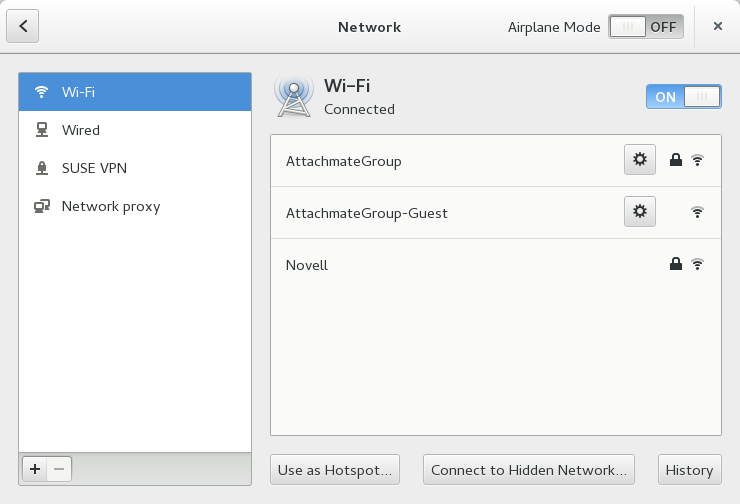

- 38.1 GNOME Network Connections Dialog

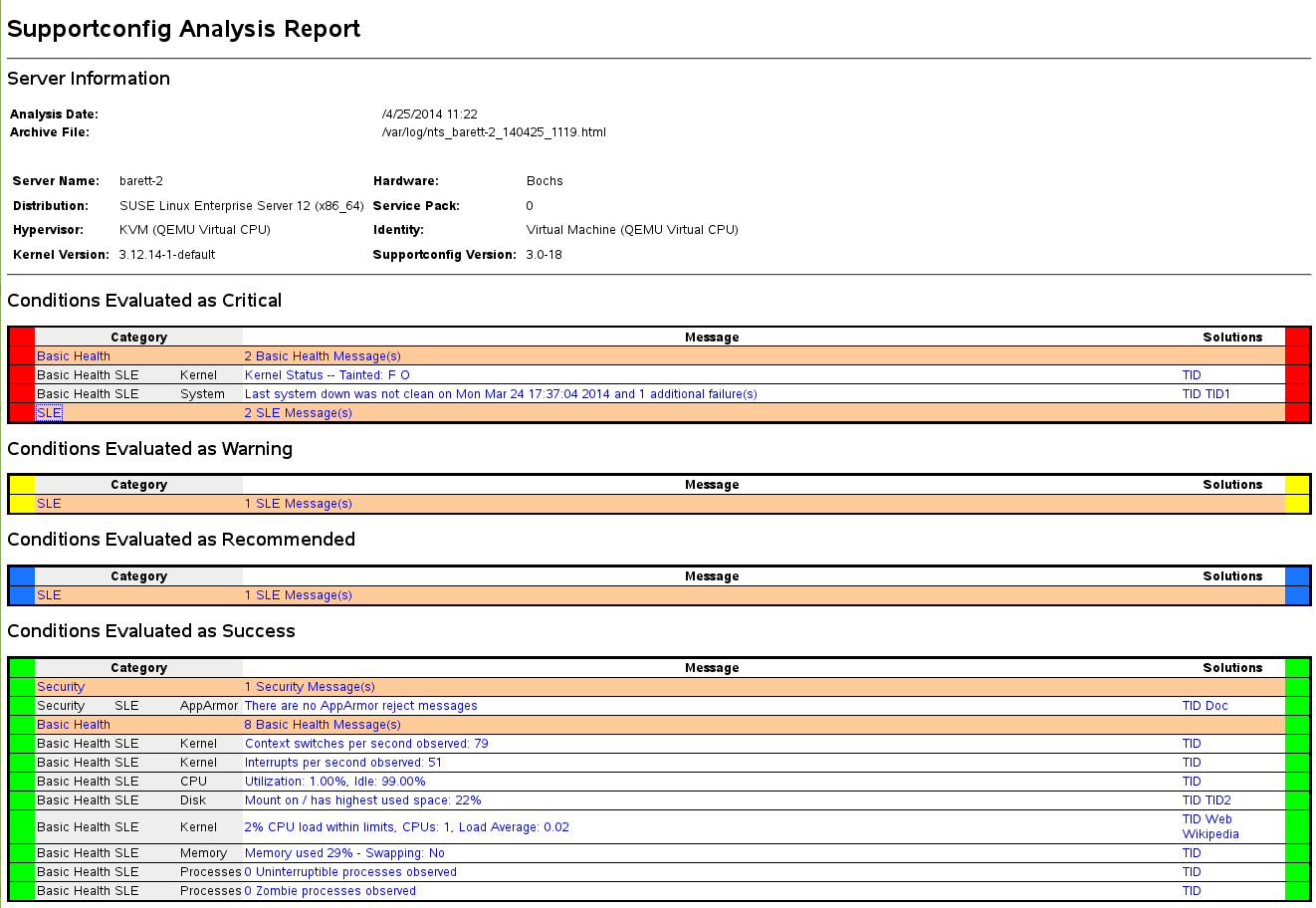

- 41.1 HTML Report Generated by SCA Tool

- 41.2 HTML Report Generated by SCA Appliance

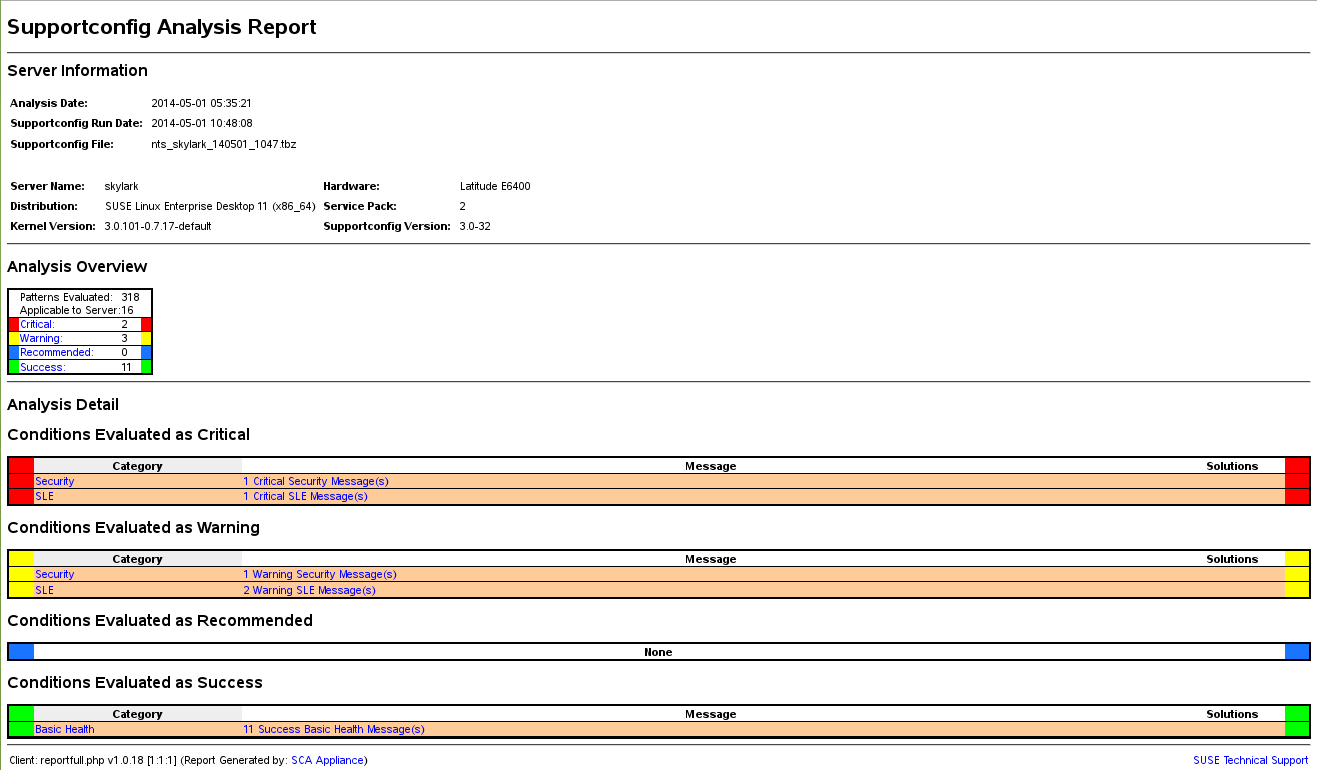

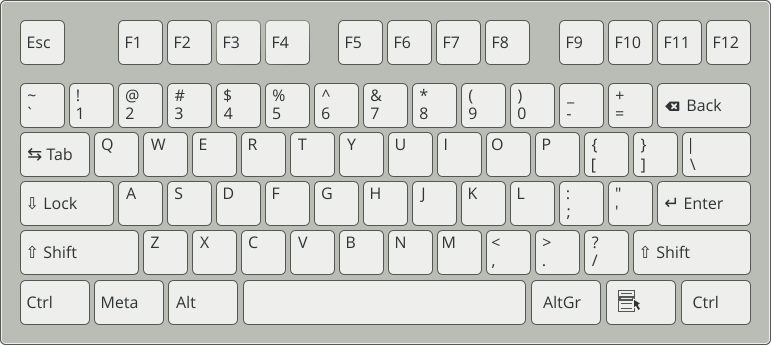

- 42.1 Checking Media

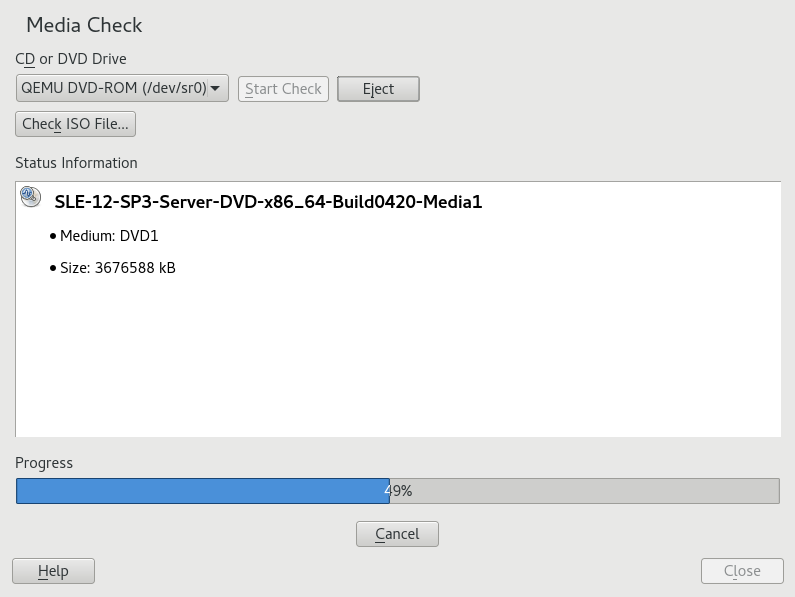

- 42.2 US Keyboard Layout

- 1.1 Bash Configuration Files for Login Shells

- 1.2 Bash Configuration Files for Non-Login Shells

- 1.3 Special Files for Bash

- 1.4 Overview of a Standard Directory Tree

- 1.5 Useful Environment Variables

- 2.1 Useful Flags and Options

- 6.1 The Most Important RPM Query Options

- 6.2 RPM Verify Options

- 14.1 Service Management Commands

- 14.2 Commands for enabling and disabling services

- 14.3 System V runlevels and

systemdtarget units - 17.1 Private IP Address Domains

- 17.2 Parameters for /etc/host.conf

- 17.3 Databases Available via /etc/nsswitch.conf

- 17.4 Configuration Options for NSS “Databases”

- 17.5 Feature Comparison between Bonding and Team

- 19.1 Generating PFL from Fontconfig rules

- 19.2 Results from Generating PFL from Fontconfig Rules with Changed Order

- 19.3 Results from Generating PFL from Fontconfig Rules

- 24.1

ulimit: Setting Resources for the User - 36.1 Commands for Managing sfcbd

- 37.1 Use Cases for NetworkManager

- 37.2 Overview of Various Wi-Fi Standards

- 40.1 Man Pages—Categories and Descriptions

- 42.1 Log files

- 42.2 System Information With the

/procFile System - 42.3 System Information With the

/sysFile System

- 1.1 A Shell Script Printing a Text

- 6.1 Zypper—List of Known Repositories

- 6.2

rpm -q -i wget - 6.3 Script to Search for Packages

- 7.1 Example timeline configuration

- 13.1 Usage of grub2-mkconfig

- 13.2 Usage of grub2-mkrescue

- 13.3 Usage of grub2-script-check

- 13.4 Usage of grub2-once

- 14.1 List Active Services

- 14.2 List Failed Services

- 14.3 List all processes belonging to a service

- 17.1 Writing IP Addresses

- 17.2 Linking IP Addresses to the Netmask

- 17.3 Sample IPv6 Address

- 17.4 IPv6 Address Specifying the Prefix Length

- 17.5 Common Network Interfaces and Some Static Routes

- 17.6

/etc/resolv.conf - 17.7

/etc/hosts - 17.8

/etc/networks - 17.9

/etc/host.conf - 17.10

/etc/nsswitch.conf - 17.11 Output of the Command ping

- 17.12 Configuration for Loadbalancing with Network Teaming

- 17.13 Configuration for DHCP Network Teaming Device

- 18.1 Error Message from

lpd - 18.2 Broadcast from the CUPS Network Server

- 19.1 Specifying Rendering Algorithms

- 19.2 Aliases and Family Name Substitutions

- 19.3 Aliases and Family Name Substitutions

- 19.4 Aliases and Family Names Substitutions

- 22.1 Example

udevRules - 24.1 Entry in /etc/crontab

- 24.2 /etc/crontab: Remove Time Stamp Files

- 24.3 ulimit: Settings in ~/.bashrc

- 27.1 Forwarding Options in named.conf

- 27.2 A Basic /etc/named.conf

- 27.3 Entry to Disable Logging

- 27.4 Zone Entry for example.com

- 27.5 Zone Entry for example.net

- 27.6 The /var/lib/named/example.com.zone File

- 27.7 Reverse Lookup

- 28.1 The Configuration File /etc/dhcpd.conf

- 28.2 Additions to the Configuration File

- 30.1 A CD-ROM Share

- 30.2 [homes] Share

- 30.3 Global Section in smb.conf

- 30.4 Using

rpcclientto Request a Windows Server 2012 Share Snapshot - 33.1 Basic Examples of Name-Based

VirtualHostEntries - 33.2 Name-Based

VirtualHostDirectives - 33.3 IP-Based

VirtualHostDirectives - 33.4 Basic

VirtualHostConfiguration - 33.5 VirtualHost CGI Configuration

- 35.1 A Request With

squidclient - 35.2 Defining ACL Rules

- 41.1 Output of

hostinfoWhen Logging In asroot

Copyright © 2006–2025 SUSE LLC and contributors. All rights reserved.

Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or (at your option) version 1.3; with the Invariant Section being this copyright notice and license. A copy of the license version 1.2 is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License”.

For SUSE trademarks, see https://www.suse.com/company/legal/. All third-party trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Trademark symbols (®, ™ etc.) denote trademarks of SUSE and its affiliates. Asterisks (*) denote third-party trademarks.

All information found in this book has been compiled with utmost attention to detail. However, this does not guarantee complete accuracy. Neither SUSE LLC, its affiliates, the authors nor the translators shall be held liable for possible errors or the consequences thereof.

About This Guide #

This guide is intended for use by professional network and system administrators during the operation of SUSE® Linux Enterprise. As such, it is solely concerned with ensuring that SUSE Linux Enterprise is properly configured and that the required services on the network are available to allow it to function properly as initially installed. This guide does not cover the process of ensuring that SUSE Linux Enterprise offers proper compatibility with your enterprise's application software or that its core functionality meets those requirements. It assumes that a full requirements audit has been done and the installation has been requested, or that a test installation for such an audit has been requested.

This guide contains the following:

- Support and Common Tasks

SUSE Linux Enterprise offers a wide range of tools to customize various aspects of the system. This part introduces a few of them. A breakdown of available device technologies, high availability configurations, and advanced administration possibilities introduces the system to the administrator.

- System

Learn more about the underlying operating system by studying this part. SUSE Linux Enterprise supports several hardware architectures and you can use this to adapt your own applications to run on SUSE Linux Enterprise. The boot loader and boot procedure information assists you in understanding how your Linux system works and how your own custom scripts and applications may blend in with it.

- Services

SUSE Linux Enterprise is designed to be a network operating system. It offers a wide range of network services, such as DNS, DHCP, Web, proxy, and authentication services. It also integrates well into heterogeneous environments, including MS Windows clients and servers.

- Mobile Computers

Laptops, and the communication between mobile devices like PDAs, or cellular phones and SUSE Linux Enterprise need some special attention. Take care for power conservation and for the integration of different devices into a changing network environment. Also get in touch with the background technologies that provide the needed functionality.

- Troubleshooting

Provides an overview of finding help and additional documentation when you need more information or want to perform specific tasks. There is also a list of the most frequent problems with explanations of how to fix them.

1 Available documentation #

- Online documentation

Our documentation is available online at https://documentation.suse.com. Browse or download the documentation in various formats.

Note: Latest updatesThe latest updates are usually available in the English-language version of this documentation.

- SUSE Knowledgebase

If you run into an issue, check out the Technical Information Documents (TIDs) that are available online at https://www.suse.com/support/kb/. Search the SUSE Knowledgebase for known solutions driven by customer need.

- Release notes

For release notes, see https://www.suse.com/releasenotes/.

- In your system

For offline use, the release notes are also available under

/usr/share/doc/release-noteson your system. The documentation for individual packages is available at/usr/share/doc/packages.Many commands are also described in their manual pages. To view them, run

man, followed by a specific command name. If themancommand is not installed on your system, install it withsudo zypper install man.

2 Improving the documentation #

Your feedback and contributions to this documentation are welcome. The following channels for giving feedback are available:

- Service requests and support

For services and support options available for your product, see https://www.suse.com/support/.

To open a service request, you need a SUSE subscription registered at SUSE Customer Center. Go to https://scc.suse.com/support/requests, log in, and click .

- Bug reports

Report issues with the documentation at https://bugzilla.suse.com/.

To simplify this process, click the icon next to a headline in the HTML version of this document. This preselects the right product and category in Bugzilla and adds a link to the current section. You can start typing your bug report right away.

A Bugzilla account is required.

- Contributions

To contribute to this documentation, click the icon next to a headline in the HTML version of this document. This will take you to the source code on GitHub, where you can open a pull request.

A GitHub account is required.

Note: only available for EnglishThe icons are only available for the English version of each document. For all other languages, use the icons instead.

For more information about the documentation environment used for this documentation, see the repository's README.

You can also report errors and send feedback concerning the documentation to <doc-team@suse.com>. Include the document title, the product version, and the publication date of the document. Additionally, include the relevant section number and title (or provide the URL) and provide a concise description of the problem.

3 Documentation conventions #

The following notices and typographic conventions are used in this document:

/etc/passwd: Directory names and file namesPLACEHOLDER: Replace PLACEHOLDER with the actual value

PATH: An environment variablels,--help: Commands, options, and parametersuser: The name of a user or grouppackage_name: The name of a software package

Alt, Alt–F1: A key to press or a key combination. Keys are shown in uppercase as on a keyboard.

, › : menu items, buttons

AMD/Intel This paragraph is only relevant for the AMD64/Intel 64 architectures. The arrows mark the beginning and the end of the text block.

IBM Z, POWER This paragraph is only relevant for the architectures

IBM ZandPOWER. The arrows mark the beginning and the end of the text block.Chapter 1, “Example chapter”: A cross-reference to another chapter in this guide.

Commands that must be run with

rootprivileges. You can also prefix these commands with thesudocommand to run them as a non-privileged user:root #commandtux >sudocommandCommands that can be run by non-privileged users:

tux >commandCommands can be split into two or multiple lines by a backslash character (

\) at the end of a line. The backslash informs the shell that the command invocation will continue after the end of the line:tux >echoa b \ c dA code block that shows both the command (preceded by a prompt) and the respective output returned by the shell:

tux >commandoutputNotices

Warning: Warning noticeVital information you must be aware of before proceeding. Warns you about security issues, potential loss of data, damage to hardware, or physical hazards.

Important: Important noticeImportant information you should be aware of before proceeding.

Note: Note noticeAdditional information, for example about differences in software versions.

Tip: Tip noticeHelpful information, like a guideline or a piece of practical advice.

Compact Notices

Additional information, for example about differences in software versions.

Helpful information, like a guideline or a piece of practical advice.

4 Support #

Find the support statement for SUSE Linux Enterprise Server and general information about technology previews below. For details about the product lifecycle, see https://www.suse.com/lifecycle. For the virtualization support status, see Book “Virtualization Guide”, Chapter 7 “Supported Hosts, Guests, and Features”.

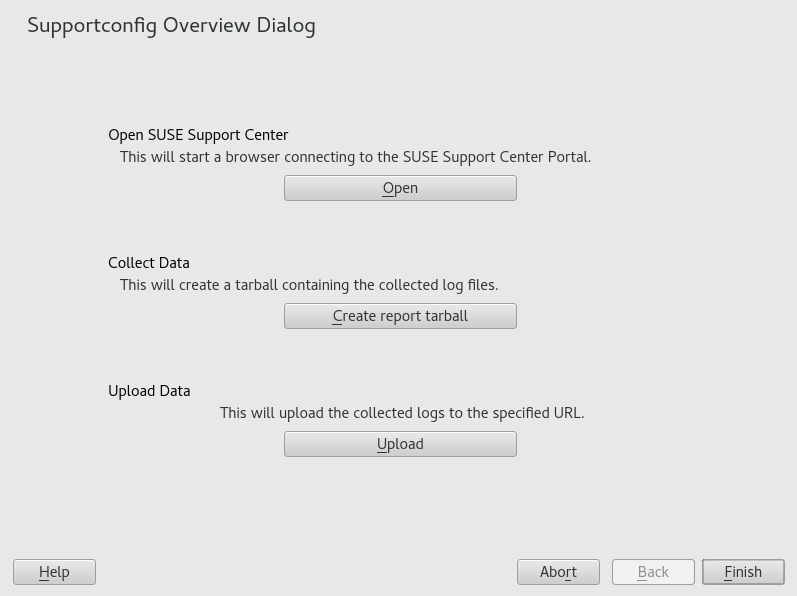

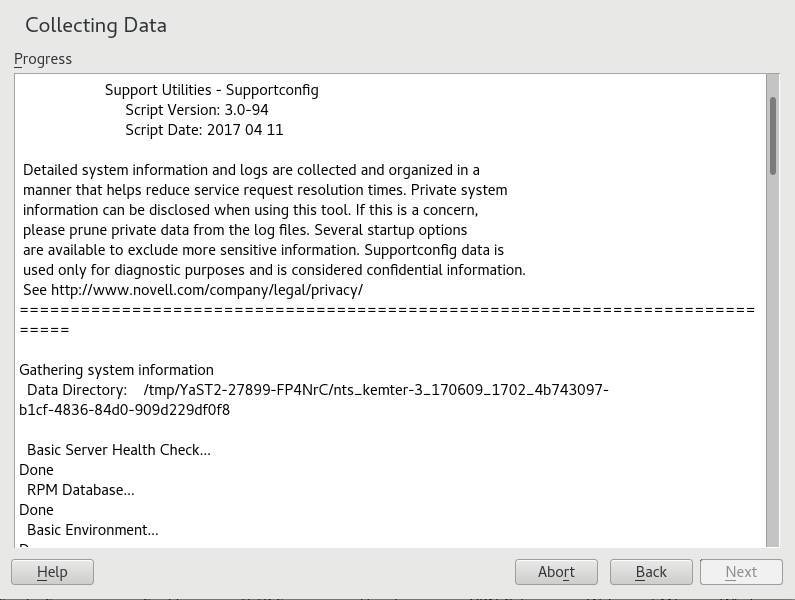

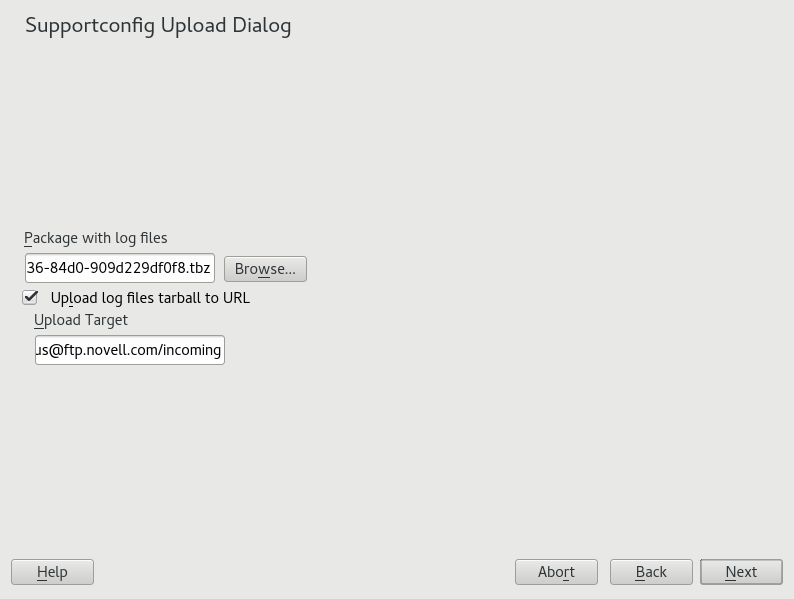

If you are entitled to support, find details on how to collect information for a support ticket at https://documentation.suse.com/sles-15/html/SLES-all/cha-adm-support.html.

4.1 Support statement for SUSE Linux Enterprise Server #

To receive support, you need an appropriate subscription with SUSE. To view the specific support offers available to you, go to https://www.suse.com/support/ and select your product.

The support levels are defined as follows:

- L1

Problem determination, which means technical support designed to provide compatibility information, usage support, ongoing maintenance, information gathering and basic troubleshooting using available documentation.

- L2

Problem isolation, which means technical support designed to analyze data, reproduce customer problems, isolate a problem area and provide a resolution for problems not resolved by Level 1 or prepare for Level 3.

- L3

Problem resolution, which means technical support designed to resolve problems by engaging engineering to resolve product defects which have been identified by Level 2 Support.

For contracted customers and partners, SUSE Linux Enterprise Server is delivered with L3 support for all packages, except for the following:

Technology previews.

Sound, graphics, fonts, and artwork.

Packages that require an additional customer contract.

Some packages shipped as part of the module Workstation Extension are L2-supported only.

Packages with names ending in -devel (containing header files and similar developer resources) will only be supported together with their main packages.

SUSE will only support the usage of original packages. That is, packages that are unchanged and not recompiled.

4.2 Technology previews #

Technology previews are packages, stacks, or features delivered by SUSE to provide glimpses into upcoming innovations. Technology previews are included for your convenience to give you a chance to test new technologies within your environment. We would appreciate your feedback. If you test a technology preview, please contact your SUSE representative and let them know about your experience and use cases. Your input is helpful for future development.

Technology previews have the following limitations:

Technology previews are still in development. Therefore, they may be functionally incomplete, unstable, or otherwise not suitable for production use.

Technology previews are not supported.

Technology previews may only be available for specific hardware architectures.

Details and functionality of technology previews are subject to change. As a result, upgrading to subsequent releases of a technology preview may be impossible and require a fresh installation.

SUSE may discover that a preview does not meet customer or market needs, or does not comply with enterprise standards. Technology previews can be removed from a product at any time. SUSE does not commit to providing a supported version of such technologies in the future.

For an overview of technology previews shipped with your product, see the release notes at https://www.suse.com/releasenotes.

Part I Common Tasks #

- 1 Bash and Bash Scripts

Today, many people use computers with a graphical user interface (GUI) like GNOME. Although they offer lots of features, their use is limited when it comes to the execution of automated tasks. Shells are a good addition to GUIs and this chapter gives you an overview of some aspects of shells, in this case Bash.

- 2 sudo

- 3 YaST Online Update

- 4 YaST

- 5 YaST in Text Mode

- 6 Managing Software with Command Line Tools

This chapter describes Zypper and RPM, two command line tools for managing software. For a definition of the terminology used in this context (for example,

repository,patch, orupdate) refer to Book “Deployment Guide”, Chapter 14 “Installing or Removing Software”, Section 14.1 “Definition of Terms”.- 7 System Recovery and Snapshot Management with Snapper

Snapper allows creating and managing file system snapshots. File system snapshots allow keeping a copy of the state of a file system at a certain point of time. The standard setup of Snapper is designed to allow rolling back system changes. However, you can also use it to create on-disk backups of user data. As the basis for this functionality, Snapper uses the Btrfs file system or thinly-provisioned LVM volumes with an XFS or Ext4 file system.

- 8 Remote Access with VNC

Virtual Network Computing (VNC) enables you to control a remote computer via a graphical desktop (as opposed to a remote shell access). VNC is platform-independent and lets you access the remote machine from any operating system.

SUSE Linux Enterprise Server supports two different kinds of VNC sessions: One-time sessions that “live” as long as the VNC connection from the client is kept up, and persistent sessions that “live” until they are explicitly terminated.

- 9 File Copying with RSync

Today, a typical user has several computers: home and workplace machines, a laptop, a smartphone or a tablet. This makes the task of keeping files and documents in sync across multiple devices all more important.

- 10 GNOME Configuration for Administrators

1 Bash and Bash Scripts #

Today, many people use computers with a graphical user interface (GUI) like GNOME. Although they offer lots of features, their use is limited when it comes to the execution of automated tasks. Shells are a good addition to GUIs and this chapter gives you an overview of some aspects of shells, in this case Bash.

1.1 What is “The Shell”? #

Traditionally, the Linux shell is Bash (Bourne again Shell). When this chapter speaks about “the shell” it means Bash. There are more shells available (ash, csh, ksh, zsh, …), each employing different features and characteristics.

1.1.1 Knowing the Bash Configuration Files #

A shell can be invoked as an:

Interactive login shell. This is used when logging in to a machine, invoking Bash with the

--loginoption or when logging in to a remote machine with SSH.Interactive non-login shell. This is normally the case when starting xterm, konsole, gnome-terminal or similar tools.

Non-interactive non-login shell. This is used when invoking a shell script at the command line.

Depending on which type of shell you use, different configuration files are being read. The following tables show the login and non-login shell configuration files.

Bash looks for its configuration files in a specific order depending on

the type of shell where it is run. Find more details on the Bash man

page (man 1 bash). Search for the headline

INVOCATION.

|

File |

Description |

|---|---|

|

|

Do not modify this file, otherwise your modifications can be destroyed during your next update! |

|

|

Use this file if you extend |

|

|

Contains system-wide configuration files for specific programs |

|

|

Insert user specific configuration for login shells here |

Note that the login shell also sources the configuration files listed under Table 1.2, “Bash Configuration Files for Non-Login Shells”.

|

|

Do not modify this file, otherwise your modifications can be destroyed during your next update! |

|

|

Use this file to insert your system-wide modifications for Bash only |

|

|

Insert user specific configuration here |

Additionally, Bash uses some more files:

|

File |

Description |

|---|---|

|

|

Contains a list of all commands you have been typing |

|

|

Executed when logging out |

|

|

User defined aliases of frequently used commands. See

|

1.1.2 The Directory Structure #

The following table provides a short overview of the most important higher-level directories that you find on a Linux system. Find more detailed information about the directories and important subdirectories in the following list.

|

Directory |

Contents |

|---|---|

|

|

Root directory—the starting point of the directory tree. |

|

|

Essential binary files, such as commands that are needed by both the system administrator and normal users. Usually also contains the shells, such as Bash. |

|

|

Static files of the boot loader. |

|

|

Files needed to access host-specific devices. |

|

|

Host-specific system configuration files. |

|

|

Holds the home directories of all users who have accounts on the system.

However, |

|

|

Essential shared libraries and kernel modules. |

|

|

Mount points for removable media. |

|

|

Mount point for temporarily mounting a file system. |

|

|

Add-on application software packages. |

|

|

Home directory for the superuser |

|

|

Essential system binaries. |

|

|

Data for services provided by the system. |

|

|

Temporary files. |

|

|

Secondary hierarchy with read-only data. |

|

|

Variable data such as log files. |

|

|

Only available if you have both Microsoft Windows* and Linux installed on your system. Contains the Windows data. |

The following list provides more detailed information and gives some examples of which files and subdirectories can be found in the directories:

/binContains the basic shell commands that may be used both by

rootand by other users. These commands includels,mkdir,cp,mv,rmandrmdir./binalso contains Bash, the default shell in SUSE Linux Enterprise Server./bootContains data required for booting, such as the boot loader, the kernel, and other data that is used before the kernel begins executing user-mode programs.

/devHolds device files that represent hardware components.

/etcContains local configuration files that control the operation of programs like the X Window System. The

/etc/init.dsubdirectory contains LSB init scripts that can be executed during the boot process./home/USERNAMEHolds the private data of every user who has an account on the system. The files located here can only be modified by their owner or by the system administrator. By default, your e-mail directory and personal desktop configuration are located here in the form of hidden files and directories, such as

.gconf/and.config.Note: Home Directory in a Network EnvironmentIf you are working in a network environment, your home directory may be mapped to a directory in the file system other than

/home./libContains the essential shared libraries needed to boot the system and to run the commands in the root file system. The Windows equivalent for shared libraries are DLL files.

/mediaContains mount points for removable media, such as CD-ROMs, flash disks, and digital cameras (if they use USB).

/mediagenerally holds any type of drive except the hard disk of your system. When your removable medium has been inserted or connected to the system and has been mounted, you can access it from here./mntThis directory provides a mount point for a temporarily mounted file system.

rootmay mount file systems here./optReserved for the installation of third-party software. Optional software and larger add-on program packages can be found here.

/rootHome directory for the

rootuser. The personal data ofrootis located here./runA tmpfs directory used by

systemdand various components./var/runis a symbolic link to/run./sbinAs the

sindicates, this directory holds utilities for the superuser./sbincontains the binaries essential for booting, restoring and recovering the system in addition to the binaries in/bin./srvHolds data for services provided by the system, such as FTP and HTTP.

/tmpThis directory is used by programs that require temporary storage of files.

Important: Cleaning up/tmpat Boot TimeData stored in

/tmpis not guaranteed to survive a system reboot. It depends, for example, on settings made in/etc/tmpfiles.d/tmp.conf./usr/usrhas nothing to do with users, but is the acronym for Unix system resources. The data in/usris static, read-only data that can be shared among various hosts compliant with theFilesystem Hierarchy Standard(FHS). This directory contains all application programs including the graphical desktops such as GNOME and establishes a secondary hierarchy in the file system./usrholds several subdirectories, such as/usr/bin,/usr/sbin,/usr/local, and/usr/share/doc./usr/binContains generally accessible programs.

/usr/sbinContains programs reserved for the system administrator, such as repair functions.

/usr/localIn this directory the system administrator can install local, distribution-independent extensions.

/usr/share/docHolds various documentation files and the release notes for your system. In the

manualsubdirectory find an online version of this manual. If more than one language is installed, this directory may contain versions of the manuals for different languages.Under

packagesfind the documentation included in the software packages installed on your system. For every package, a subdirectory/usr/share/doc/packages/PACKAGENAMEis created that often holds README files for the package and sometimes examples, configuration files or additional scripts.If Howtos are installed on your system

/usr/share/docalso holds thehowtosubdirectory in which to find additional documentation on many tasks related to the setup and operation of Linux software./varWhereas

/usrholds static, read-only data,/varis for data which is written during system operation and thus is variable data, such as log files or spooling data. For an overview of the most important log files you can find under/var/log/, refer to Table 42.1, “Log files”./windowsOnly available if you have both Microsoft Windows and Linux installed on your system. Contains the Windows data available on the Windows partition of your system. Whether you can edit the data in this directory depends on the file system your Windows partition uses. If it is FAT32, you can open and edit the files in this directory. For NTFS, SUSE Linux Enterprise Server also includes write access support. However, the driver for the NTFS-3g file system has limited functionality.

1.2 Writing Shell Scripts #

Shell scripts provide a convenient way to perform a wide range of tasks: collecting data, searching for a word or phrase in a text and other useful things. The following example shows a small shell script that prints a text:

#!/bin/sh 1 # Output the following line: 2 echo "Hello World" 3

The first line begins with the Shebang

characters ( | |

The second line is a comment beginning with the hash sign. It is recommended to comment difficult lines to remember what they do. | |

The third line uses the built-in command |

Before you can run this script you need some prerequisites:

Every script should contain a Shebang line (as in the example above). If the line is missing, you need to call the interpreter manually.

You can save the script wherever you want. However, it is a good idea to save it in a directory where the shell can find it. The search path in a shell is determined by the environment variable

PATH. Usually a normal user does not have write access to/usr/bin. Therefore it is recommended to save your scripts in the users' directory~/bin/. The above example gets the namehello.sh.The script needs executable permissions. Set the permissions with the following command:

chmod +x ~/bin/hello.sh

If you have fulfilled all of the above prerequisites, you can execute the script in the following ways:

As Absolute Path. The script can be executed with an absolute path. In our case, it is

~/bin/hello.sh.Everywhere. If the

PATHenvironment variable contains the directory where the script is located, you can execute the script withhello.sh.

1.3 Redirecting Command Events #

Each command can use three channels, either for input or output:

Standard Output. This is the default output channel. Whenever a command prints something, it uses the standard output channel.

Standard Input. If a command needs input from users or other commands, it uses this channel.

Standard Error. Commands use this channel for error reporting.

To redirect these channels, there are the following possibilities:

Command > FileSaves the output of the command into a file, an existing file will be deleted. For example, the

lscommand writes its output into the filelisting.txt:ls > listing.txt

Command >> FileAppends the output of the command to a file. For example, the

lscommand appends its output to the filelisting.txt:ls >> listing.txt

Command < FileReads the file as input for the given command. For example, the

readcommand reads in the content of the file into the variable:read a < foo

Command1 | Command2Redirects the output of the left command as input for the right command. For example, the

catcommand outputs the content of the/proc/cpuinfofile. This output is used bygrepto filter only those lines which containcpu:cat /proc/cpuinfo | grep cpu

Every channel has a file descriptor: 0 (zero) for

standard input, 1 for standard output and 2 for standard error. It is

allowed to insert this file descriptor before a < or

> character. For example, the following line searches

for a file starting with foo, but suppresses its errors

by redirecting it to /dev/null:

find / -name "foo*" 2>/dev/null

1.4 Using Aliases #

An alias is a shortcut definition of one or more commands. The syntax for an alias is:

alias NAME=DEFINITION

For example, the following line defines an alias lt that

outputs a long listing (option -l), sorts it by

modification time (-t), and prints it in reverse sorted order (-r):

alias lt='ls -ltr'

To view all alias definitions, use alias. Remove your

alias with unalias and the corresponding alias name.

1.5 Using Variables in Bash #

A shell variable can be global or local. Global variables, or environment variables, can be accessed in all shells. In contrast, local variables are visible in the current shell only.

To view all environment variables, use the printenv

command. If you need to know the value of a variable, insert the name of

your variable as an argument:

printenv PATH

A variable, be it global or local, can also be viewed with

echo:

echo $PATH

To set a local variable, use a variable name followed by the equal sign, followed by the value:

PROJECT="SLED"

Do not insert spaces around the equal sign, otherwise you get an error. To

set an environment variable, use export:

export NAME="tux"

To remove a variable, use unset:

unset NAME

The following table contains some common environment variables which can be used in you shell scripts:

|

|

the home directory of the current user |

|

|

the current host name |

|

|

when a tool is localized, it uses the language from this environment

variable. English can also be set to |

|

|

the search path of the shell, a list of directories separated by colon |

|

|

specifies the normal prompt printed before each command |

|

|

specifies the secondary prompt printed when you execute a multi-line command |

|

|

current working directory |

|

|

the current user |

1.5.1 Using Argument Variables #

For example, if you have the script foo.sh you can

execute it like this:

foo.sh "Tux Penguin" 2000

To access all the arguments which are passed to your script, you need

positional parameters. These are $1 for the first argument,

$2 for the second, and so on. You can have up to nine

parameters. To get the script name, use $0.

The following script foo.sh prints all arguments from 1

to 4:

#!/bin/sh echo \"$1\" \"$2\" \"$3\" \"$4\"

If you execute this script with the above arguments, you get:

"Tux Penguin" "2000" "" ""

1.5.2 Using Variable Substitution #

Variable substitutions apply a pattern to the content of a variable either from the left or right side. The following list contains the possible syntax forms:

${VAR#pattern}removes the shortest possible match from the left:

file=/home/tux/book/book.tar.bz2 echo ${file#*/} home/tux/book/book.tar.bz2${VAR##pattern}removes the longest possible match from the left:

file=/home/tux/book/book.tar.bz2 echo ${file##*/} book.tar.bz2${VAR%pattern}removes the shortest possible match from the right:

file=/home/tux/book/book.tar.bz2 echo ${file%.*} /home/tux/book/book.tar${VAR%%pattern}removes the longest possible match from the right:

file=/home/tux/book/book.tar.bz2 echo ${file%%.*} /home/tux/book/book${VAR/pattern_1/pattern_2}substitutes the content of VAR from the PATTERN_1 with PATTERN_2:

file=/home/tux/book/book.tar.bz2 echo ${file/tux/wilber} /home/wilber/book/book.tar.bz2

1.6 Grouping and Combining Commands #

Shells allow you to concatenate and group commands for conditional execution. Each command returns an exit code which determines the success or failure of its operation. If it is 0 (zero) the command was successful, everything else marks an error which is specific to the command.

The following list shows, how commands can be grouped:

Command1 ; Command2executes the commands in sequential order. The exit code is not checked. The following line displays the content of the file with

catand then prints its file properties withlsregardless of their exit codes:cat filelist.txt ; ls -l filelist.txt

Command1 && Command2runs the right command, if the left command was successful (logical AND). The following line displays the content of the file and prints its file properties only, when the previous command was successful (compare it with the previous entry in this list):

cat filelist.txt && ls -l filelist.txt

Command1 || Command2runs the right command, when the left command has failed (logical OR). The following line creates only a directory in

/home/wilber/barwhen the creation of the directory in/home/tux/foohas failed:mkdir /home/tux/foo || mkdir /home/wilber/bar

funcname(){ ... }creates a shell function. You can use the positional parameters to access its arguments. The following line defines the function

helloto print a short message:hello() { echo "Hello $1"; }You can call this function like this:

hello Tux

which prints:

Hello Tux

1.7 Working with Common Flow Constructs #

To control the flow of your script, a shell has while,

if, for and case

constructs.

1.7.1 The if Control Command #

The if command is used to check expressions. For

example, the following code tests whether the current user is Tux:

if test $USER = "tux"; then echo "Hello Tux." else echo "You are not Tux." fi

The test expression can be as complex or simple as possible. The following

expression checks if the file foo.txt exists:

if test -e /tmp/foo.txt ; then echo "Found foo.txt" fi

The test expression can also be abbreviated in angled brackets:

if [ -e /tmp/foo.txt ] ; then echo "Found foo.txt" fi

Find more useful expressions at http://www.cyberciti.biz/nixcraft/linux/docs/uniqlinuxfeatures/lsst/ch03sec02.html.

1.7.2 Creating Loops with the for Command #

The for loop allows you to execute commands to a list of

entries. For example, the following code prints some information about PNG

files in the current directory:

for i in *.png; do ls -l $i done

1.8 For More Information #

Important information about Bash is provided in the man pages man

bash. More about this topic can be found in the following list:

https://tldp.org/LDP/Bash-Beginners-Guide/html/index.html—Bash Guide for Beginners

https://tldp.org/HOWTO/Bash-Prog-Intro-HOWTO.html—BASH Programming - Introduction HOW-TO

https://tldp.org/LDP/abs/html/index.html—Advanced Bash-Scripting Guide

http://www.grymoire.com/Unix/Sh.html—Sh - the Bourne Shell

Many commands and system utilities need to be run as root to modify

files and/or perform tasks that only the super user is allowed to. For

security reasons and to avoid accidentally running dangerous commands, it is

generally advisable not to log in directly as root. Instead, it is

recommended to work as a normal, unprivileged user and use the sudo

command to run commands with elevated privileges.

On SUSE Linux Enterprise Server, sudo is configured by default to work similarly to su.

However, sudo offers the possibility to allow users to run commands with

privileges of any other user in a highly configurable manner. This can be

used to assign roles with specific privileges to certain users and groups. It

is for example possible to allow members of the group users to run a

command with the privileges of wilber. Access to the command can be

further restricted by, for example, forbidding to specify any command

options. While su always requires the root password for authentication

with PAM, sudo can be configured to authenticate with your own credentials.

This increases security by not having to share the root password. For

example, you can allow members of the group users to run a command

frobnicate as wilber, with the restriction that

no arguments are specified. This can be used to assign roles with specific

abilities to certain users and groups.

2.1 Basic sudo Usage #

sudo is simple to use, yet very powerful.

2.1.1 Running a Single Command #

Logged in as normal user, you can run any command as root by

adding sudo before it. It will prompt for the root password and, if

authenticated successfully, run the command as root:

tux >id -un1 tuxtux >sudo id -unroot's password:2 roottux >id -untux3tux >sudo id -un4 root

The | |

The password is not shown during input, neither as clear text nor as bullets. | |

Only commands started with | |

The elevated privileges persist for a certain period of time, so you

do not need to provide the |

I/O redirection does not work as you would probably expect:

tux >sudo echo s > /proc/sysrq-trigger bash: /proc/sysrq-trigger: Permission deniedtux >sudo cat < /proc/1/maps bash: /proc/1/maps: Permission denied

Only the echo/cat binary is run with

elevated privileges, while the redirection is performed by the user's

shell with user privileges. You can either start a shell like in

Section 2.1.2, “Starting a Shell” or use the dd utility

instead:

echo s | sudo dd of=/proc/sysrq-trigger sudo dd if=/proc/1/maps | cat

2.1.2 Starting a Shell #

Having to add sudo before every command can be cumbersome. While you

could specify a shell as a command sudo bash, it is

recommended to rather use one of the built-in mechanisms to start a shell:

sudo -s (<command>)Starts a shell specified by the

SHELLenvironment variable or the target user's default shell. If a command is given, it is passed to the shell (with the-coption), else the shell is run in interactive mode.tux:~ >sudo -i root's password:root:/home/tux #exittux:~ >sudo -i (<command>)Like

-s, but starts the shell as login shell. This means that the shell's start-up files (.profileetc.) are processed and the current working directory is set to the target user's home directory.tux:~ >sudo -i root's password:root:~ #exittux:~ >

2.1.3 Environment Variables #

By default, sudo does not propagate environment variables:

tux >ENVVAR=test env | grep ENVVAR ENVVAR=testtux >ENVVAR=test sudo env | grep ENVVAR root's password: 1tux >

The empty output shows that the environment variable

|

This behavior can be changed by the env_reset option,

see Table 2.1, “Useful Flags and Options”.

2.2 Configuring sudo #

sudo is a very flexible tool with extensive configuration.

If you accidentally locked yourself out of sudo, use su

- and the root password to get a root shell.

To fix the error, run visudo.

2.2.1 Editing the Configuration Files #

The main policy configuration file for sudo is

/etc/sudoers. As it is possible to lock yourself out

of the system due to errors in this file, it is strongly

recommended to use visudo for editing. It will prevent

simultaneous changes to the opened file and check for syntax errors before

saving the modifications.

Despite its name, you can also use editors other than vi by setting the

EDITOR environment variable, for example:

sudo EDITOR=/usr/bin/nano visudo

However, the /etc/sudoers file itself is supplied by

the system packages and modifications may break on updates. Therefore, it

is recommended to put custom configuration into files in the

/etc/sudoers.d/ directory. Any file in there is

automatically included. To create or edit a file in that subdirectory, run:

sudo visudo -f /etc/sudoers.d/NAME

Alternatively with a different editor (for example

nano):

sudo EDITOR=/usr/bin/nano visudo -f /etc/sudoers.d/NAME

/etc/sudoers.d

The #includedir command in

/etc/sudoers, used for

/etc/sudoers.d, ignores files that end in

~ (tilde) or contain a . (dot).

For more information on the visudo command, run

man 8 visudo.

2.2.2 Basic sudoers Configuration Syntax #

In the sudoers configuration files, there are two types of options: strings and flags. While strings can contain any value, flags can be turned either ON or OFF. The most important syntax constructs for sudoers configuration files are:

# Everything on a line after a # gets ignored 1 Defaults !insults # Disable the insults flag 2 Defaults env_keep += "DISPLAY HOME" # Add DISPLAY and HOME to env_keep tux ALL = NOPASSWD: /usr/bin/frobnicate, PASSWD: /usr/bin/journalctl 3

There are two exceptions: | |

Remove the | |

|

Option name |

Description |

Example |

|---|---|---|

targetpw

|

This flag controls whether the invoking user is required to enter the

password of the target user (ON) (for example |

Defaults targetpw # Turn targetpw flag ON |

rootpw

|

If set, |

Defaults !rootpw # Turn rootpw flag OFF |

env_reset

|

If set, |

Defaults env_reset # Turn env_reset flag ON |

env_keep

|

List of environment variables to keep when the

|

# Set env_keep to contain EDITOR and PROMPT Defaults env_keep = "EDITOR PROMPT" Defaults env_keep += "JRE_HOME" # Add JRE_HOME Defaults env_keep -= "JRE_HOME" # Remove JRE_HOME |

env_delete

|

List of environment variables to remove when the

|

# Set env_delete to contain EDITOR and PROMPT Defaults env_delete = "EDITOR PROMPT" Defaults env_delete += "JRE_HOME" # Add JRE_HOME Defaults env_delete -= "JRE_HOME" # Remove JRE_HOME |

The Defaults token can also be used to create aliases

for a collection of users, hosts, and commands. Furthermore, it is possible

to apply an option only to a specific set of users.

For detailed information about the /etc/sudoers

configuration file, consult man 5 sudoers.

2.2.3 Rules in sudoers #

Rules in the sudoers configuration can be very complex, so this section

will only cover the basics. Each rule follows the basic scheme

([] marks optional parts):

#Who Where As whom Tag What User_List Host_List = [(User_List)] [NOPASSWD:|PASSWD:] Cmnd_List

User_ListOne or more (separated by

,) identifiers: Either a user name, a group in the format%GROUPNAMEor a user ID in the format#UID. Negation can be performed with a!prefix.Host_ListOne or more (separated by

,) identifiers: Either a (fully qualified) host name or an IP address. Negation can be performed with a!prefix.ALLis the usual choice forHost_List.NOPASSWD:|PASSWD:The user will not be prompted for a password when running commands matching

CMDSPECafterNOPASSWD:.PASSWDis the default, it only needs to be specified when both are on the same line:tux ALL = PASSWD: /usr/bin/foo, NOPASSWD: /usr/bin/bar

Cmnd_ListOne or more (separated by

,) specifiers: A path to an executable, followed by allowed arguments or nothing./usr/bin/foo # Anything allowed /usr/bin/foo bar # Only "/usr/bin/foo bar" allowed /usr/bin/foo "" # No arguments allowed

ALL can be used as User_List,

Host_List, and Cmnd_List.

A rule that allows tux to run all commands as root without

entering a password:

tux ALL = NOPASSWD: ALL

A rule that allows tux to run systemctl restart

apache2:

tux ALL = /usr/bin/systemctl restart apache2

A rule that allows tux to run wall as

admin with no arguments:

tux ALL = (admin) /usr/bin/wall ""

Constructs of the kind

ALL ALL = ALL

must not be used without Defaults

targetpw, otherwise anyone can run commands as root.

When specifying the group name in the sudoers file, make sure that you use the the NetBIOS domain name instead of the realm, for example:

%DOMAIN\\GROUP_NAME ALL = (ALL) ALL

Keep in mind that when using winbindd, the format also depends on the winbind separator option in the smb.conf file. By default, it is \. If it is changed, for example, to +, then the account format in sudoers file must be DOMAIN+GROUP_NAME.

2.3 Common Use Cases #

Although the default configuration is often sufficient for simple setups and desktop environments, custom configurations can be very useful.

2.3.1 Using sudo without root password #

By design, members of the group

wheel can run all commands

with sudo as root. The following procedure explains how to add a user

account to the wheel group.

Verify that the

wheelgroup exists:tux >getent group wheelIf the previous command returned no result, install the system-group-wheel package that creates the

wheelgroup:tux >sudozypper install system-group-wheelAdd your user account to the group

wheel.If your user account is not already a member of the

wheelgroup, add it using thesudo usermod -a -G wheel USERNAMEcommand. Log out and log in again to enable the change. Verify that the change was successful by running thegroups USERNAMEcommand.Authenticate with the user account's normal password.

Create the file

/etc/sudoers.d/userpwusing thevisudocommand (see Section 2.2.1, “Editing the Configuration Files”) and add the following:Defaults !targetpw

Select a new default rule.

Depending on whether you want users to re-enter their passwords, uncomment the specific line in

/etc/sudoersand comment out the default rule.## Uncomment to allow members of group wheel to execute any command # %wheel ALL=(ALL) ALL ## Same thing without a password # %wheel ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD: ALL

Make the default rule more restrictive

Comment out or remove the allow-everything rule in

/etc/sudoers:ALL ALL=(ALL) ALL # WARNING! Only use this together with 'Defaults targetpw'!

Warning: Dangerous rule in sudoersDo not forget this step, otherwise any user can execute any command as

root!Test the configuration

Try to run

sudoas member and non-member ofwheel.tux:~ >groups users wheeltux:~ >sudo id -un tux's password: rootwilber:~ >groups userswilber:~ >sudo id -un wilber is not in the sudoers file. This incident will be reported.

2.3.2 Using sudo with X.Org Applications #

When starting graphical applications with sudo, you will encounter the

following error:

tux > sudo xterm

xterm: Xt error: Can't open display: %s

xterm: DISPLAY is not setYaST will pick the ncurses interface instead of the graphical one.

To use X.Org in applications started with sudo, the environment

variables DISPLAY and XAUTHORITY need to be

propagated. To configure this, create the file

/etc/sudoers.d/xorg, (see

Section 2.2.1, “Editing the Configuration Files”) and add the following line:

Defaults env_keep += "DISPLAY XAUTHORITY"

If not set already, set the XAUTHORITY variable as follows:

export XAUTHORITY=~/.Xauthority

Now X.Org applications can be run as usual:

sudo yast2

2.4 More Information #

A quick overview about the available command line switches can be retrieved

by sudo --help. An explanation and other important

information can be found in the man page: man 8 sudo,

while the configuration is documented in man 5 sudoers.

3 YaST Online Update #

SUSE offers a continuous stream of software security updates for your product. By default, the update applet is used to keep your system up-to-date. Refer to Book “Deployment Guide”, Chapter 14 “Installing or Removing Software”, Section 14.5 “Keeping the System Up-to-date” for further information on the update applet. This chapter covers the alternative tool for updating software packages: YaST Online Update.

The current patches for SUSE® Linux Enterprise Server are available from an update software repository. If you have registered your product during the installation, an update repository is already configured. If you have not registered SUSE Linux Enterprise Server, you can do so by starting the in YaST. Alternatively, you can manually add an update repository from a source you trust. To add or remove repositories, start the Repository Manager with › in YaST. Learn more about the Repository Manager in Book “Deployment Guide”, Chapter 14 “Installing or Removing Software”, Section 14.4 “Managing Software Repositories and Services”.

If you are not able to access the update catalog, this might be because of an expired subscription. Normally, SUSE Linux Enterprise Server comes with a one-year or three-year subscription, during which you have access to the update catalog. This access will be denied after the subscription ends.

If an access to the update catalog is denied, you will see a warning message prompting you to visit the SUSE Customer Center and check your subscription. The SUSE Customer Center is available at https://scc.suse.com//.

SUSE provides updates with different relevance levels:

- Security Updates

Fix severe security hazards and should always be installed.

- Recommended Updates

Fix issues that could compromise your computer.

- Optional Updates

Fix non-security relevant issues or provide enhancements.

3.1 The Online Update Dialog #

To open the YaST dialog, start YaST and

select › . Alternatively, start it from the command

line with yast2 online_update.

The window consists of four sections.

The section on the left lists the available

patches for SUSE Linux Enterprise Server. The patches are sorted by security relevance:

security, recommended, and

optional. You can change the view of the

section by selecting one of the following options

from :

- (default view)

Non-installed patches that apply to packages installed on your system.

Patches that either apply to packages not installed on your system, or patches that have requirements which have already have been fulfilled (because the relevant packages have already been updated from another source).

All patches available for SUSE Linux Enterprise Server.

Each list entry in the section consists of a

symbol and the patch name. For an overview of the possible symbols and their

meaning, press Shift–F1. Actions required by Security and

Recommended patches are automatically preset. These

actions are ,

and .

If you install an up-to-date package from a repository other than the update repository, the requirements of a patch for this package may be fulfilled with this installation. In this case a check mark is displayed in front of the patch summary. The patch will be visible in the list until you mark it for installation. This will in fact not install the patch (because the package already is up-to-date), but mark the patch as having been installed.

Select an entry in the section to view a short at the bottom left corner of the dialog. The upper right section lists the packages included in the selected patch (a patch can consist of several packages). Click an entry in the upper right section to view details about the respective package that is included in the patch.

3.2 Installing Patches #

The YaST Online Update dialog allows you to either install all available patches at once or manually select the desired patches. You may also revert patches that have been applied to the system.

By default, all new patches (except optional ones) that

are currently available for your system are already marked for installation.

They will be applied automatically once you click

or .

If one or multiple patches require a system reboot, you will be notified

about this before the patch installation starts. You can then either decide

to continue with the installation of the selected patches, skip the

installation of all patches that need rebooting and install the rest, or go

back to the manual patch selection.

Start YaST and select › .

To automatically apply all new patches (except

optionalones) that are currently available for your system, press or .First modify the selection of patches that you want to apply:

Use the respective filters and views that the interface provides. For details, refer to Section 3.1, “The Online Update Dialog”.

Select or deselect patches according to your needs and wishes by right-clicking the patch and choosing the respective action from the context menu.

Important: Always Apply Security UpdatesDo not deselect any

security-related patches without a very good reason. These patches fix severe security hazards and prevent your system from being exploited.Most patches include updates for several packages. If you want to change actions for single packages, right-click a package in the package view and choose an action.

To confirm your selection and apply the selected patches, proceed with or .

After the installation is complete, click to leave the YaST . Your system is now up-to-date.

3.3 Automatic Online Update #

YaST also offers the possibility to set up an automatic update with daily,

weekly or monthly schedule. To use the respective module, you need to

install the

yast2-online-update-configuration

package first.

By default, updates are downloaded as delta RPMs. Since rebuilding RPM packages from delta RPMs is a memory- and processor-intensive task, certain setups or hardware configurations might require you to disable the use of delta RPMs for the sake of performance.

Some patches, such as kernel updates or packages requiring license agreements, require user interaction, which would cause the automatic update procedure to stop. You can configure to skip patches that require user interaction.

After installation, start YaST and select › .

Alternatively, start the module with

yast2 online_update_configurationfrom the command line.Activate .

Choose the update interval: , , or .

To automatically accept any license agreements, activate .

Select if you want to in case you want the update procedure to proceed fully automatically.

Important: Skipping PatchesIf you select to skip any packages that require interaction, run a manual occasionally to install those patches, too. Otherwise you might miss important patches.

To automatically install all packages recommended by updated packages, activate .

To disable the use of delta RPMs (for performance reasons), deactivate .

To filter the patches by category (such as security or recommended), activate and add the appropriate patch categories from the list. Only patches of the selected categories will be installed. Others will be skipped.

Confirm your configuration with .

The automatic online update does not automatically restart the system afterward. If there are package updates that require a system reboot, you need to do this manually.

YaST is the installation and configuration tool for SUSE Linux Enterprise Server. It has a graphical interface and the capability to customize your system quickly during and after the installation. It can be used to set up hardware, configure the network, system services, and tune your security settings.

4.1 YaST interface overview #

YaST has two graphical interfaces: one for use with graphical desktop environments like KDE and GNOME, and an ncurses-based pseudo-graphical interface for use on systems without an X server (see Chapter 5, YaST in Text Mode).

In the graphical version of YaST, all modules in YaST are grouped by category, and the navigation sidebar allows you to quickly access modules in the desired category. The search field at the top makes it possible to find modules by their names. To find a specific module, enter its name into the search field, and you should see the modules that match the entered string as you type.

The list of installed modules for the ncurses-based and GUI version of YaST may differ. Before starting any YaST module, verify that it is installed for the version of YaST that you are using.

4.2 Useful key combinations #

The graphical version of YaST supports keyboard shortcuts

- Print Screen

Take and save a screenshot. May not be available when YaST is running under some desktop environments.

- Shift–F4

Enable/disable the color palette optimized for vision impaired users.

- Shift–F7

Enable/disable logging of debug messages.

- Shift–F8

Open a file dialog to save log files to a non-standard location.

- Ctrl–Shift–Alt–D

Send a DebugEvent. YaST modules can react to this by executing special debugging actions. The result depends on the specific YaST module.

- Ctrl–Shift–Alt–M

Start/stop macro recorder.

- Ctrl–Shift–Alt–P

Replay macro.

- Ctrl–Shift–Alt–S

Show style sheet editor.

- Ctrl–Shift–Alt–T

Dump widget tree to the log file.

- Ctrl–Shift–Alt–X

Open a terminal window (xterm). Useful for installation process via VNC.

- Ctrl–Shift–Alt–Y

Show widget tree browser.

5 YaST in Text Mode #

This section is intended for system administrators and experts who do not run an X server on their systems and depend on the text-based installation tool. It provides basic information about starting and operating YaST in text mode.

YaST in text mode uses the ncurses library to provide an easy pseudo-graphical user interface. The ncurses library is installed by default. The minimum supported size of the terminal emulator in which to run YaST is 80x25 characters.

When you start YaST in text mode, the YaST control center appears (see Figure 5.1). The main window consists of three areas. The left frame features the categories to which the various modules belong. This frame is active when YaST is started and therefore it is marked by a bold white border. The active category is selected. The right frame provides an overview of the modules available in the active category. The bottom frame contains the buttons for and .

When you start the YaST control center, the category is selected automatically. Use ↓ and ↑ to change the category. To select a module from the category, activate the right frame with → and then use ↓ and ↑ to select the module. Keep the arrow keys pressed to scroll through the list of available modules. After selecting a module, press Enter to start it.

Various buttons or selection fields in the module contain a highlighted letter (yellow by default). Use Alt–highlighted_letter to select a button directly instead of navigating there with →|. Exit the YaST control center by pressing Alt–Q or by selecting and pressing Enter.

If a YaST dialog gets corrupted or distorted (for example, while resizing the window), press Ctrl–L to refresh and restore its contents.

5.2 Advanced Key Combinations #

YaST in text mode has a set of advanced key combinations.

- Shift–F1

Show a list of advanced hotkeys.

- Shift–F4

Change color schema.

- Ctrl–\

Quit the application.

- Ctrl–L

Refresh screen.

- Ctrl–D F1

Show a list of advanced hotkeys.

- Ctrl–D Shift–D

Dump dialog to the log file as a screenshot.

- Ctrl–D Shift–Y

Open YDialogSpy to see the widget hierarchy.

5.3 Restriction of Key Combinations #

If your window manager uses global Alt combinations, the Alt combinations in YaST might not work. Keys like Alt or Shift can also be occupied by the settings of the terminal.

- Replacing Alt with Esc

Alt shortcuts can be executed with Esc instead of Alt. For example, Esc–H replaces Alt–H. (First press Esc, then press H.)

- Backward and Forward Navigation with Ctrl–F and Ctrl–B

If the Alt and Shift combinations are occupied by the window manager or the terminal, use the combinations Ctrl–F (forward) and Ctrl–B (backward) instead.

- Restriction of Function Keys

The function keys (F1 ... F12) are also used for functions. Certain function keys might be occupied by the terminal and may not be available for YaST. However, the Alt key combinations and function keys should always be fully available on a pure text console.

5.4 YaST Command Line Options #

Besides the text mode interface, YaST provides a pure command line interface. To get a list of YaST command line options, enter:

yast -h

5.4.1 Starting the Individual Modules #

To save time, the individual YaST modules can be started directly. To start a module, enter:

yast <module_name>

View a list of all module names available on your system with yast

-l or yast --list. Start the network module,

for example, with yast lan.

5.4.2 Installing Packages from the Command Line #

If you know a package name and the package is provided by any of your

active installation repositories, you can use the command line option

-i to install the package:

yast -i <package_name>

or

yast --install <package_name>

PACKAGE_NAME can be a single short package name

(for example gvim) installed with

dependency checking, or the full path to an RPM package

which is installed without dependency checking.

If you need a command line based software management utility with functionality beyond what YaST provides, consider using Zypper. This utility uses the same software management library that is also the foundation for the YaST package manager. The basic usage of Zypper is covered in Section 6.1, “Using Zypper”.

5.4.3 Command Line Parameters of the YaST Modules #

To use YaST functionality in scripts, YaST provides command line support for individual modules. Not all modules have command line support. To display the available options of a module, enter:

yast <module_name> help

If a module does not provide command line support, the module is started in text mode and the following message appears:

This YaST module does not support the command line interface.

6 Managing Software with Command Line Tools #

This chapter describes Zypper and RPM, two command line tools for managing

software. For a definition of the terminology used in this context (for

example, repository, patch, or

update) refer to

Book “Deployment Guide”, Chapter 14 “Installing or Removing Software”, Section 14.1 “Definition of Terms”.

6.1 Using Zypper #

Zypper is a command line package manager for installing, updating and removing packages a well as for managing repositories. It is especially useful for accomplishing remote software management tasks or managing software from shell scripts.

6.1.1 General Usage #

The general syntax of Zypper is:

zypper[--global-options]COMMAND[--command-options][arguments]

The components enclosed in brackets are not required. See zypper

help for a list of general options and all commands. To get help

for a specific command, type zypper help

COMMAND.

- Zypper Commands

The simplest way to execute Zypper is to type its name, followed by a command. For example, to apply all needed patches to the system, use:

tux >sudo zypper patch- Global Options

Additionally, you can choose from one or more global options by typing them immediately before the command:

tux >sudo zypper --non-interactive patchIn the above example, the option

--non-interactivemeans that the command is run without asking anything (automatically applying the default answers).- Command-Specific Options

To use options that are specific to a particular command, type them immediately after the command:

tux >sudo zypper patch --auto-agree-with-licensesIn the above example,

--auto-agree-with-licensesis used to apply all needed patches to a system without you being asked to confirm any licenses. Instead, licenses will be accepted automatically.- Arguments

Some commands require one or more arguments. For example, when using the command

install, you need to specify which package or which packages you want to install:tux >sudo zypper install mplayerSome options also require a single argument. The following command will list all known patterns:

tux >zypper search -t pattern

You can combine all of the above. For example, the following command will

install the

aspell-de

and

aspell-fr

packages from the factory repository while being verbose:

tux > sudo zypper -v install --from factory aspell-de aspell-fr

The --from option makes sure to keep all repositories

enabled (for solving any dependencies) while requesting the package from the

specified repository.

Most Zypper commands have a dry-run option that does a

simulation of the given command. It can be used for test purposes.

tux > sudo zypper remove --dry-run MozillaFirefox

Zypper supports the global --userdata

STRING option. You can specify a string

with this option, which gets written to Zypper's log files and plug-ins

(such as the Btrfs plug-in). It can be used to mark and identify

transactions in log files.

tux > sudo zypper --userdata STRING patch6.1.2 Installing and Removing Software with Zypper #

To install or remove packages, use the following commands:

tux >sudozypper install PACKAGE_NAMEtux >sudozypper remove PACKAGE_NAME

Do not remove mandatory system packages like glibc , zypper , kernel . If they are removed, the system can become unstable or stop working altogether.

6.1.2.1 Selecting Which Packages to Install or Remove #

There are various ways to address packages with the commands

zypper install and zypper remove.

- By Exact Package Name

tux >sudo zypper install MozillaFirefox- By Exact Package Name and Version Number

tux >sudo zypper install MozillaFirefox-52.2- By Repository Alias and Package Name

tux >sudo zypper install mozilla:MozillaFirefoxWhere

mozillais the alias of the repository from which to install.- By Package Name Using Wild Cards

You can select all packages that have names starting or ending with a certain string. Use wild cards with care, especially when removing packages. The following command will install all packages starting with “Moz”:

tux >sudo zypper install 'Moz*'Tip: Removing all-debuginfoPackagesWhen debugging a problem, you sometimes need to temporarily install a lot of

-debuginfopackages which give you more information about running processes. After your debugging session finishes and you need to clean the environment, run the following:tux >sudo zypper remove '*-debuginfo'- By Capability

For example, if you want to install a Perl module without knowing the name of the package, capabilities come in handy:

tux >sudo zypper install firefox- By Capability, Hardware Architecture, or Version

Together with a capability, you can specify a hardware architecture and a version:

The name of the desired hardware architecture is appended to the capability after a full stop. For example, to specify the AMD64/Intel 64 architectures (which in Zypper is named

x86_64), use:tux >sudo zypper install 'firefox.x86_64'Versions must be appended to the end of the string and must be preceded by an operator:

<(lesser than),<=(lesser than or equal),=(equal),>=(greater than or equal),>(greater than).tux >sudo zypper install 'firefox>=52.2'You can also combine a hardware architecture and version requirement:

tux >sudo zypper install 'firefox.x86_64>=52.2'

- By Path to the RPM file

You can also specify a local or remote path to a package:

tux >sudo zypper install /tmp/install/MozillaFirefox.rpmtux >sudo zypper install http://download.example.com/MozillaFirefox.rpm

6.1.2.2 Combining Installation and Removal of Packages #

To install and remove packages simultaneously, use the

+/- modifiers. To install

emacs

and simultaneously remove

vim

, use:

tux > sudo zypper install emacs -vimTo remove emacs and simultaneously install vim , use:

tux > sudo zypper remove emacs +vim

To prevent the package name starting with the - being

interpreted as a command option, always use it as the second argument. If

this is not possible, precede it with --:

tux >sudo zypper install -emacs +vim # Wrongtux >sudo zypper install vim -emacs # Correcttux >sudo zypper install -- -emacs +vim # Correcttux >sudo zypper remove emacs +vim # Correct

6.1.2.3 Cleaning Up Dependencies of Removed Packages #

If (together with a certain package), you automatically want to remove any

packages that become unneeded after removing the specified package, use the

--clean-deps option:

tux >sudozypper rm --clean-deps PACKAGE_NAME

6.1.2.4 Using Zypper in Scripts #

By default, Zypper asks for a confirmation before installing or removing a

selected package, or when a problem occurs. You can override this behavior

using the --non-interactive option. This option must be

given before the actual command (install,

remove, and patch), as can be seen in

the following:

tux >sudo zypper--non-interactiveinstall PACKAGE_NAME

This option allows the use of Zypper in scripts and cron jobs.

6.1.2.5 Installing or Downloading Source Packages #

To install the corresponding source package of a package, use:

tux > zypper source-install PACKAGE_NAME

When executed as root, the default location to install source

packages is /usr/src/packages/ and

~/rpmbuild when run as user. These values can be

changed in your local rpm configuration.

This command will also install the build dependencies of the specified

package. If you do not want this, add the switch -D:

tux > sudo zypper source-install -D PACKAGE_NAME

To install only the build dependencies use -d.

tux > sudo zypper source-install -d PACKAGE_NAMEOf course, this will only work if you have the repository with the source packages enabled in your repository list (it is added by default, but not enabled). See Section 6.1.5, “Managing Repositories with Zypper” for details on repository management.

A list of all source packages available in your repositories can be obtained with:

tux > zypper search -t srcpackageYou can also download source packages for all installed packages to a local directory. To download source packages, use:

tux > zypper source-download

The default download directory is

/var/cache/zypper/source-download. You can change it

using the --directory option. To only show missing or

extraneous packages without downloading or deleting anything, use the

--status option. To delete extraneous source packages, use

the --delete option. To disable deleting, use the

--no-delete option.