Large Scale SUSE OpenStack Clouds - An Architecture Guide #

Cloud

This document provides an overview of the architecture and key aspects of an Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) platform based on SUSE products and is specifically designed and targeted for cloud native workloads running in a large environment. The architecture is based on real world implementations that have been deployed at scale with enterprise customers and utilizes best practices from these setups.

Disclaimer: Documents published as part of the SUSE Best Practices series have been contributed voluntarily by SUSE employees and third parties. They are meant to serve as examples of how particular actions can be performed. They have been compiled with utmost attention to detail. However, this does not guarantee complete accuracy. SUSE cannot verify that actions described in these documents do what is claimed or whether actions described have unintended consequences. SUSE LLC, its affiliates, the authors, and the translators may not be held liable for possible errors or the consequences thereof.

1 About This Document #

This document describes how to design and build a large and scalable private cloud to provide Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) based on open source products and open APIs. Private cloud setups are advantageous for both Internet service providers and customers, in comparison to conventional IT setups. From a customer’s point of view, running their own workload inside a public cloud allows for agility and flexibility. For service providers, public cloud setups leverage the principle of economy of scale. This means that even with a growing demand, it remains easy and convenient to serve customers.

Together, by means of a public cloud environment, customers and providers create an integrated and optimized enterprise and accelerate digital transformation across the business.

Large scale cloud platforms are designed and built to fulfill the requirements of a modern and future-proof data center. In such an environment, applications are created on virtual machines or container-based, highly automated and with a fast life-cycle (DevOps approach), and are not limited to specific uses cases.

This document provides an overview of the architecture and key aspects of an IaaS platform based on SUSE products. It is specifically designed and targeted for cloud native workloads running in a large environment. The architecture is based on real world implementations that have been deployed at scale with enterprise customers and utilizes best practices from these setups.

1.1 Cloud Primer #

The term Cloud is present everywhere in the IT industry. However, it is important to define the term Private Cloud as it is used throughout this document.

1.1.1 Cloud Computing and Conventional Setups #

Most conventional IT setups share the same basic design tenets; typically they are customer-specific. This means they were built for a certain customer and only upon said customer’s request. Conventional setups do not share resources with other setups. All resources present in a conventional IT setup are made available to the customer for whom the setup was originally created only.

Conventional IT setups come with several disadvantages for both the Internet Service Provider (ISP) and the customer. The most important aspects are listed below:

Conventional setups come with long lead times, as they need to be planned and the required hardware must then be acquired. This can take several weeks.

Conventional setups come with high investment costs to customers for both the development of an actual software solution and the acquisition of hardware (including infrastructure hardware such as network switches or load-balancers).

Conventional setups tend to see service providers locking customers into a contract for several years, limiting the flexibility of the customer.

Conventional setups have a low degree of automation. They require several manual steps to be performed both by the customer and the ISP.

The concept of Cloud Computing was introduced several years ago as a way to deal with the disadvantages of conventional setups. Clouds enforce a certain role shift, especially from the service provider’s point of view. Instead of serving individual customers with solutions tailor-made to their demands, a cloud setup turns the service provider into a platform provider. A cloud provider’s main responsibility is to run and maintain a platform that makes computing, storage, and network resources available to customers dynamically and on an on-demand principle.

The following list contains a number of factors that are very basic design tenets of clouds:

Cloud environments allow for seamless scale-out of the platform. This means in case of resource shortage, it is easy for the provider to extend the amount of available resources.

Cloud environments are based on the principle of API services and the ability to issue requests for resources to said API services using a defined and well-known protocol such as REST. Using such APIs, services can be implemented in clouds.

Cloud environments decouple hardware and software and use Software Defined Networking (SDN) and Software Defined Storage (SDS). Because all core functionality is written in software and exists inside the platform itself, the manual configuration of infrastructure hardware such as networking switches becomes unnecessary.

Cloud environments allow customers to service themselves based on SDN, SDS, and the aforementioned APIs.

Cloud environments come with a higher level of automation from both the customers' and the provider’s point of view. This saves time on tasks that, in conventional setups, need to be done manually.

Running a public cloud forces an ISP to transform their business. Rather than providing individual services to individual customers, they can use a public cloud that provides an overarching platform that customers are free to use at their own discretion.

1.1.2 OpenStack as the Base for the Cloud #

By using software built for the sole purpose of running public clouds, ISPs improve the level of automation and standardization in their platform. Combined with additional tools the OpenStack cloud computing platform allows enterprises to launch a public cloud product quickly and conveniently. Over the last few years, OpenStack has become the number one open source solution to run public clouds all over the world.

Some of the key features of the OpenStack cloud computing software are as follows:

OpenStack has a well-proven track record of being the perfect solution for large public cloud environments. Organizations such as CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, or SAP use OpenStack for their cloud platforms.

OpenStack has the principle of well-documented, standardized, open APIs at the heart of its concept. This allows users to leverage the full power of the API principle.

OpenStack is open source software licensed under the terms of the Apache License. This effectively helps avoid vendor lock-in that comes along with most commercial products. Because COTS (Commercial off-the-shelf) hardware can be used, there is also no vendor lock-in on the hardware side.

OpenStack does not require an ISP to trust the manufacturer of a software product blindly. Because of its nature as an open source solution, the source code is open for everybody to audit and examine.

OpenStack is not dominated by individual vendors but by the OpenStack Foundation, of which everybody can become a member.

OpenStack, thanks to its large user and developer community, comes with a lot of useful components and features. These components make operating the cloud and using its features a convenient task.

OpenStack supports multi-tenant setups. This effectively allows large numbers of customers to use one and the same cloud platform.

OpenStack is made available by its developers to users free of charge, which results in extremely low initial setup costs. Also, license fees and license renewal costs do not apply.

The SUSE OpenStack Cloud product is based on the upstream OpenStack project. It enables the operator to smoothly deal with the complexity of the project and control the deployment, the daily operation and the maintenance of the platform. The integrated deployment tool allows for an easy setup and deployment of the complex infrastructure. The professional support provided by SUSE ensures the provision of a stable and available platform, turning an open source project in an enterprise grade software solution.

1.1.3 Scope of This Document #

The following paragraphs define the purpose of this document.

Based on best practices, this document describes the most basic design tenets of a cloud environment built for massive scale-out and a large target size. It does not provide specific implementation details, such as the required configuration for individual components. One objective of this document is to outline which decisions during the design phase are important for the creation of a scalable future-proof cloud architecture.

As the details for such a design depend on a lot of parameters, this document cannot provide a one-size-fits-all solution. Examples show possibilities and options, and can help you design your own solution.

As such, this document does explicitly not aim to replace any official SUSE product documentation provided at https://documentation.suse.com/. There are various reference documents available for SUSE OpenStack Cloud, SUSE Enterprise Storage or SUSE Linux Enterprise Server, infrastructure management solutions or patch concepts like SUSE Manager or the Subscriptions Management Tool, and SUSE Linux Enterprise Linux High Availability Extension. In addition to this guide, we recommend referring to the official documentation applicable to your respective setup.

For implementation-specific documentation, refer to the documentation at https://documentation.suse.com/. SUSE has provided documentation prevalent to the deployment, administration, and usage for SUSE Enterprise Storage and SUSE OpenStack Cloud.

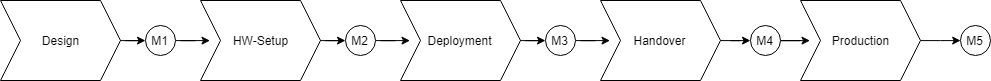

Details specific to a particular customer, environment, or business case are determined by the customer and SUSE during a Design and Implementation Workshop. See also section Section 6, “Implementation Phases”. This document does not deal with specific details.

1.2 Target Audience #

The target audience of this guide are decision makers and application, cloud, and network architects. After reading this document, you should be able to understand the basic architecture of large scale clouds and how clouds can be used to solve your business challenges.

OpenStack, thanks to its versatility and flexibility, allows for all operation models. This document focuses on the provider point-of-view and explains how customers can use SUSE OpenStack Cloud to build seamlessly scalable, large cloud environments for IaaS services.

1.2.1 IaaS, PaaS, Serverless: Operation Models for Applications in Clouds #

In cloud environments, providers typically have different offerings for different requirements on the customers' side. These are called "as-a-Service" offerings, such as Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS), Platform as a Service (PaaS) or Software as a Service (SaaS). In recent times, the term "serverless computing" is also commonly used.

All these terms describe models to operate particular environments and applications inside a cloud computing environment. They differ when it comes to defining the provider’s and the customer’s responsibilities for running the platform.

Infrastructure as a Service: The provider’s sole job is to run and operate the platform to provide customers with arbitrary amounts of compute, storage, and network resources. Running and managing actual applications in the platform is the responsibility of the customer.

Platform as a Service: In a PaaS setup, the provider does not only offer virtual compute, storage, and network resources, but also several integration tools to combine them properly. For example, users needing a database can acquire it with a few mouse clicks as result of a Database as a Service (DBaaS) offering instead of having to set up a database in a virtual machine themselves.

Software as a Service: This operation model describes a design where the cloud provider takes care of running the virtual machines and the actual application for the customers (which is why this operation model resembles "managed services" from the conventional world). The user is only consuming the service and does not care about the underlying infrastructure.

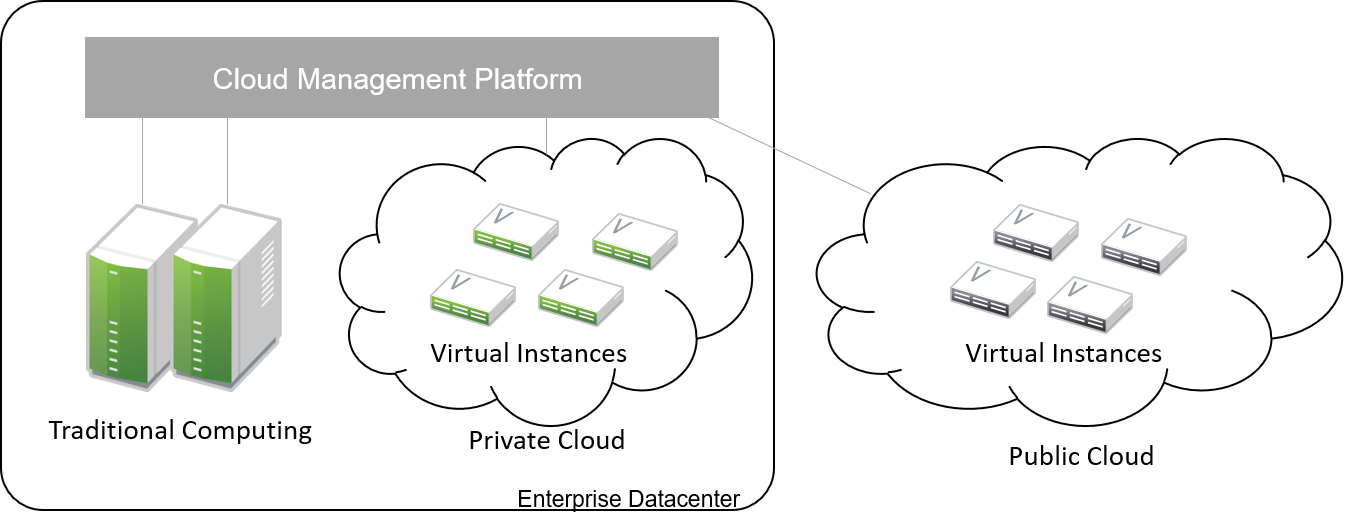

1.2.2 Private, Public, Hybrid #

There are three ways for customers to consume services provided by cloud setups:

Private Cloud: A private cloud is run internally by a company for own purposes only. It is not available for usage to the public.

Public Cloud: A public cloud environment is run by a company to offer compute, storage, and network resources to the wide public, often giving users the opportunity to register an account themselves and start using the cloud services immediately.

Hybrid Cloud: When following a hybrid cloud approach, customers use services offered by public cloud environments (such as Amazon AWS or Microsoft Azure) and services offered by an own private cloud.

The cloud setup described in this guide can serve as a public cloud or a private cloud. Hybrid considerations are, however, not within the scope of this document.

1.2.3 Compute, Storage, Network #

The three main aspects of IaaS are compute, storage, and networking. These aspects deserve a separate discussion in the context of a large cloud environment. This technical guide elaborates on all factors separately in the respective chapters. The minimum viable product assumed to be the desired result is a virtual machine with attached block storage that has working connectivity to the Internet, with all of these components being provided virtualized or software-defined.

1.3 The Design Principles #

Although every business is unique and every customer implementation comes with different requirements, there is a small set of basic requirements that all cloud environments have in common.

To build your IaaS solution, you need at least these resources:

Hardware (standard industry servers, Commercial off-the-shelf [COTS]) to run the cloud, control servers, administration servers, and host storage. Commodity hardware (one or two different types for the whole platform) is used for cost efficiency.

Standard OSI Layer 2 network hardware

Open source software to provide basic cloud functionality to implement the IaaS offering, including SDN, the operating system for said servers and a solution for SDS.

1.3.1 Design Principles, Goals and Features #

The following list describes the basic design tenets that were considered while designing the highly scalable cloud that is the subject of this guide.

Scalability: At any point in time, it must be possible to extend the cloud’s resources by adding additional nodes for compute or storage purposes.

Resilience: The cloud service must be robust and fault-tolerant. A concept for high availability must be in place.

Standardization: Open standards, open source software, open APIs that are well documented and commodity hardware (COTS) allow for high flexibility and help to avoid vendor lock-in.

The old world and the new world: The platform must be able to handle cloud-native applications and traditional or legacy workloads, with a clear focus on cloud-native applications.

Some examples for typical workloads are:

Traditional root VMs (hosted)

Orchestrated applications (cloud optimized)

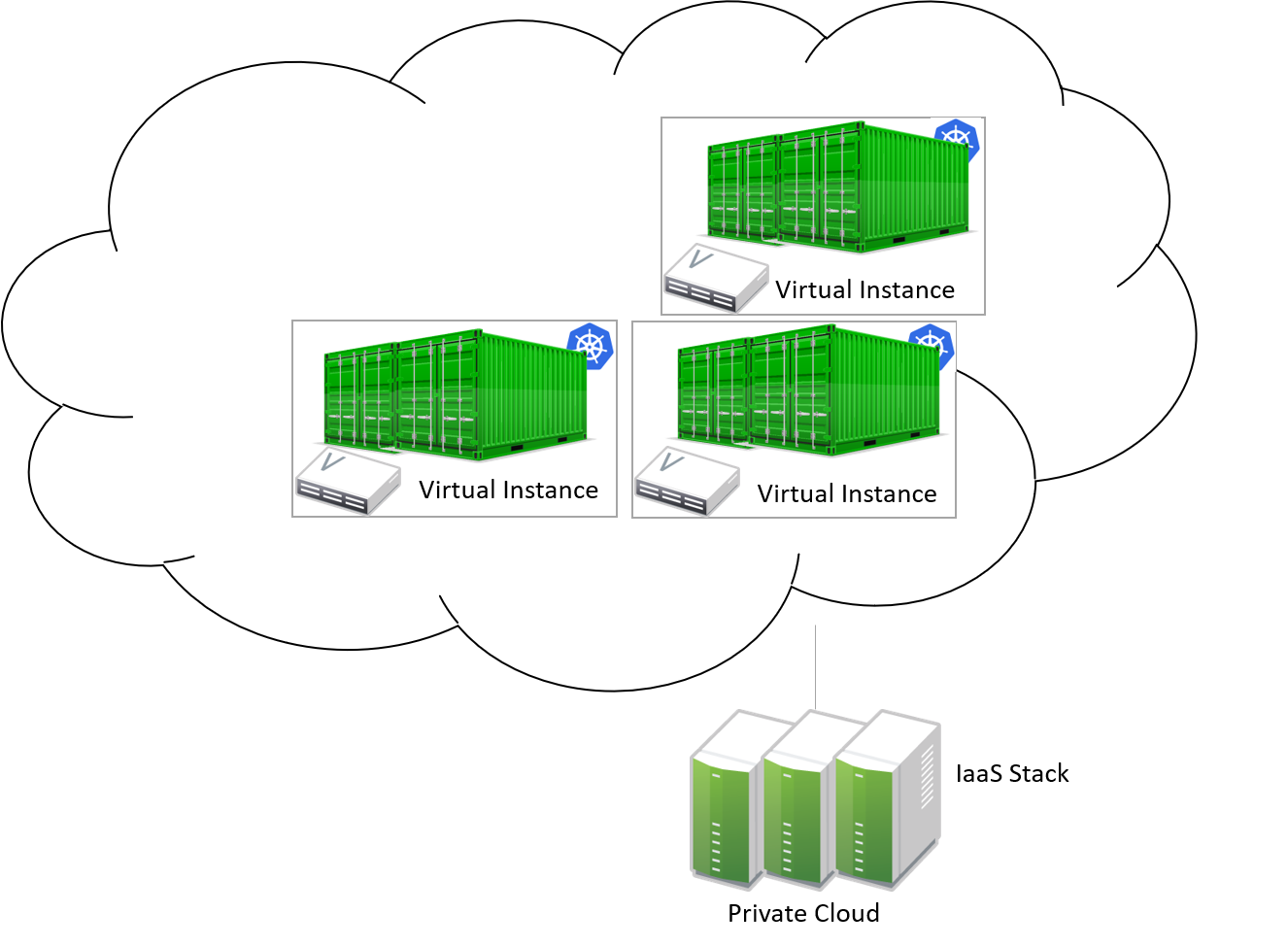

Cloud-native workloads, for example BOSH (to deploy a Cloud Foundry PaaS solution)

Container-based solutions

1.3.2 Workload Types for Cloud Environments #

Cloud computing has fundamentally changed the way how applications are rolled out for production use. While conventional applications typically follow a monolithic approach, modern applications built according to agile standards are based on numerous small components, these are called "micro services". This document refers to conventional applications as "traditional" and to applications following the new paradigm as "cloud-native".

There are, however, applications or workloads that do not fit perfectly into either of these categories, effectively creating a gray area in which special requirements exist. Traditional applications (for example legacy workloads, sometimes also referred to as 'pets' or 'kitten') are for sure not to disappear anytime soon. Any IaaS platform must be able to deal with traditional and with cloud-native workloads. The necessity to store data permanently is one of the biggest challenges in that context.

An IaaS platform such as SUSE OpenStack Cloud is optimized for cloud-native workloads and allows these to leverage the existing functionality the best possible way. Running such cloud-native workloads on a SUSE OpenStack Cloud platform means the following for the service:

Stateless: The service stores no local data and can be restarted at any time. All data needs to be stored externally in a data store.

Automated: The installation of the server is automated and no manual configuration is needed.

Scale out: More performance of the application can be achieved by starting (adding) new instances.

Availability: The availability of a service depends on his redundancy.

Applications that do not follow the cloud-native approach work in a public cloud environment but do not leverage most of the platforms' features. SUSE OpenStack Cloud offers an option to include hypervisors also in a high-availability configuration. A failure of a hypervisor is detected and the failed instances are restarted on remaining hypervisors. This helps to operate traditional workloads in a cloud-native optimized environment.

1.4 Business Drivers and Use Cases #

Businesses in differing industries and application segments are enforcing the adoption of cloud principles in their environments. While the reasons for that are as diverse as the customers requirements themselves, there are a few common goals that most enterprises share. The main motivation is the need:

For more flexibility in the own IT setup.

For a higher level of automation.

For competitive innovation.

For lower times-to-market when creating new products and applications.

For the migration of legacy application and workloads.

To identify disposable components in the own environment.

To accelerate the own growth and performance.

To reduce IT costs (CAPEX/OPEX).

All these factors play a vibrant role in the decision to deliver services in a cloud-native manner and move more applications to the cloud.

1.5 Bimodal IT #

Modern IT companies have developed a way of working that allows them to be agile and quick when developing new features and yet protect existing processes and systems. This can be crucial for a company. Often, such legacy processes and systems cannot be replaced at ease or at all. By following such a model, being agile and innovative on the one hand and protecting existing and critical infrastructure at the other hand, companies can meet the needs of today’s fast-paced IT industry. This is what many refer to as "Bimodal IT".

In said scheme, Mode 1 is responsible for providing enterprise-class IT at constant speeds (traditional workloads, "legacy") and Mode 2 is to develop and deliver cloud-native applications using principles such as Continuous Integration (CI) and Continuous Delivery (CD) at high velocity. Successful companies deliver both items in an optimized way. The IaaS platform outlined in this document supports companies by being a solution for both needs. The companies deploying such a solution benefit from the following:

A highly cost-effective, rapidly responsible and elastic IT that is very well aligned with its actual business needs to support the bimodal IT operations model.

A large portfolio of business and IT services that effectively leverage the best features provided by the underlying IaaS solution, allowing for seamless flexibility (applications can be built exactly as necessary and run wherever they are required).

The ability to map business processes to applications.

The ability to innovate faster while leveraging already-existing servers and capabilities, allowing for very short times-to-market.

1.5.1 Cloud Use Cases #

This document explains how service providers for private or public clouds build and operate a cloud designed to meet the needs of both Mode 1 and Mode 2 IT environments. Possible ways to use an environment like the one described in this document are:

The provisioning of an IaaS layer for enterprise and cloud providers

PaaS and SaaS offerings.

Allowing Cloud Service Providers (CSP) the ability to use, market, and sell their own services on top of an existing IaaS layer.

The increase of automation in their own environment based on the cloud orchestration services.

Provisioning infrastructure for DevOps and agile environments.

Each of the mentioned scenarios however has a specific business case behind it. This means that companies need to decide on the solution they want to provide before building out. Depending on the use case, there are minimal differences that lead to great effects when the solution is in place. Even smallest design decisions directly influence how well the platform is suited for what it is expected to do. Getting help from experts on this subject is recommended.

1.5.2 SLA Considerations #

When you plan a cloud environment and determine your use case, take into account as early as possible the Service Level Agreement (SLA) that the platform is expected to be delivered on. To define a proper SLA, the functionality of the platform must be clear and understood. The provider running the cloud also needs to define what kind of provider they want to be. As an example, all major public cloud providers clearly distinct between their work (which is providing a working platform) and anything that the customers might do on it. For the latter part of the work, the customer bears the sole responsibility.

Of course, the answer to this question also depends on the kind of cloud that is supposed to be created. Private clouds constructed for specific use cases face other requirements than large clouds made available to the public.

A cloud takes the control services in the focus of the SLA. The running workload on top of a hypervisor is in the responsibility of the user - and mostly not part of the SLA.

2 Architecture #

Getting a large-scale cloud environment right is a complex task. This chapter’s purpose is to paint the bigger picture of all the factors you need to consider. After an introduction into the principle of the economy of scale, this chapter outlines the main components of an OpenStack cloud and how these work together. A special focus is laid on designing a resilient and stable scale-out setup along with its individual layers and the needed considerations. Lastly, a typical OpenStack architecture is shown to serve as a valid example.

In general, cloud platforms have a complex design and still allow for large scalability. But what does scalability in cloud environments mean?

2.1 Scalability in Clouds #

Scalability is a word that most administrators are familiar with. However, a lot of different definitions of scalability exist and the word is often used in different contexts. Therefore, it is important to provide a definition of what scalability is for the purpose of this document.

When talking about processes at scale, administrators intend to extend the load that a specific setup can process by adding new hardware. The way new hardware is added depends on local conditions and can vary when looking at different setups.

Until recently, the term scalability typically was used to refer to a process called "scale-up" or "vertical scaling". This describes a process in which existing hardware is extended so that it can handle more load. Adding more RAM to an existing server, a stronger CPU to a node or additional hard disks to an existing SAN storage appliance are typical examples for scaling up. The issue with this approach is that it cannot be pursued any further because of physical limitations. As an example, the physical server’s memory banks with the biggest RAM modules may already be in use. This means you cannot expand your server’s memory anymore. It may also be impossible to replace the CPU in a server simply because for the given CPU socket, when no more powerful CPUs are available. Extending SANs can also fail as all device slots of the SAN appliance are already in use with the largest hard disks available for this model.

Not being able to scale-up a system further used to be a large issue in the past. Often, the only possibility to work around the problem was to buy completely new, more capable hardware that would be able to cope with the load present. That was an expensive and not always successful strategy.

The opposite of the process to scale-up or vertically scale is "scale-out" or "horizontal scaling". This approach is fundamentally different and assumes that there is no point in extending the existing infrastructure by replacing individual hardware components. Instead, in scale-out scenarios, the idea is to add new machines to the setup to distribute the load more evenly to more target systems within the installation. This is a superior approach to scale-up approaches because the only limiting factor is the physical space that is available in the datacenter. Thanks to dark fibre connections and other modern technologies, it is even possible to create new datacenter sites and connect those to existing sites to accommodate for seamless scale-out processes.

Not all scalability approaches work for all environments. The ability to scale-out requires the software in use to support this operational mode. Cloud solutions, such as OpenStack, are built for scale-out environments and can scale in a horizontal manner at the core of their functionality. Legacy software, in contrast to that, may only support scale-up scenarios.

As this document is about scalability in massively scalable environments, the best scalability approach is to scale-out (horizontal scalability). Whenever "scalability" is mentioned in this document, it references to scale-out processes, unless noted differently in the respective section or paragraph.

2.2 Cloud Computing Primer #

Similar to scalability, "cloud" is also used as a technical term in an almost indefinite number of contexts. This document elaborates on the architecture of large-scale cloud environments based on SUSE OpenStack Cloud. Therefore it is appropriate to define "cloud" and "cloud software" in the context of this document.

Conventional IT setups are usually a turn-key solution delivered to the customer for a specific purpose. The customer rarely takes care of running and operating the solution themselves. Instead, the IT service provider does that for them. This is static and can be unsatisfying for the customer or the service provider.

In cloud setups, service providers become platform providers. Their main responsibility is to run a platform whose services customers can consume at their own discretion. In addition to running the platform and providing resources, these providers also need to offer a way for customers to run the services themselves. This means consuming services without having to contact the service provider each time. The hardware that is used in datacenters cannot provide what it takes to offer the described functionalities without additional software. For the purpose of this document, "cloud software" is software that creates a bridge between the platform or infrastructure, and the customers. This allows them to consume the available resources as dynamically as possible.

In summary, the following attributes can be used to define "cloud":

Self Service portal / API access

Network based

Pooling of existing resources

Consumption based metering

2.3 OpenStack Primer #

OpenStack is the best-known open source cloud solution currently available at the market. It is the fundamental technology for the SUSE OpenStack Cloud product and plays an important role when building a large scale-out cloud based on SUSE products. An OpenStack Cloud also consists of several and important components. The following paragraphs provide an overview of the components of an OpenStack cloud and you a quick introduction into OpenStack and how OpenStack can help you to build a scalable compute and storage platform.

2.3.1 The OpenStack History #

The OpenStack project originally started as a joint venture between NASA and the American hosting provider, Rackspace. NASA controllers had found out that many of their scientists were conducting experiments for which they ordered hardware. When their experiments were finished, often the hardware would not be reused, while scientists in other departments were ordering new hardware for their respective experiments. The idea behind OpenStack was to create a tool to centrally administer an arbitrary amount of compute resources and to allow the scientists to consume these resources. Rackspace brought in the OpenStack Swift object storage service, which is explained in deeper detail in chapter 4.

In 2012, NASA withdrew from OpenStack as an active contributor. Since OpenStack’s official launch in 2010, dozens of companies have decided to adopt OpenStack, including solutions from large system vendors such as SUSE, as their primary cloud technology. Today, the project is stable and reliable, and the functionalities are constantly improved. OpenStack has become the ideal fundament when building a large scale-out environment.

At the time of writing, OpenStack consists of more than 30 services. Not all of them are required for a basic cloud implementation; the number of core services is considered to be six (and even out of those only 5 are strictly necessary). For a minimum viable cloud setup, a few additional supporting services are also required. The following paragraphs provide a more detailed description of the OpenStack base services.

2.3.2 Supporting Services: RabbitMQ #

OpenStack follows a strictly decentralized approach. Most OpenStack projects (and the ones described in the following paragraphs in particular) are not made of a single service but consist of many small services that often run on different hosts. All these services require a way to exchange messages between each other. Message protocols such as the AMQP standard exist for exactly that purpose and OpenStack is deployed along with the RabbitMQ message bus. RabbitMQ is one of the oldest AMQP implementations and written in the Erlang programming language. Several tools in the OpenStack universe use RabbitMQ to send and receive messages. Every OpenStack setup needs RabbitMQ. For better performance and redundancy, large-scale environments usually have more than one RabbitMQ instance running. More details about the ideal architecture of services for RabbitMQ and other services are explained further down in this chapter.

2.3.3 Supporting Services: MariaDB #

A second supporting service that is included in most OpenStack setups is MariaDB (or its predecessor MySQL). Almost all OpenStack services use MariaDB to store their internal metadata in a persistent manner. As the overall number of requests to the databases is large, like RabbitMQ, MariaDB can be rolled out in a highly available scale-out manner in cloud environments. This can, for example, happen together with the Galera Multi-master replication solution.

2.3.4 Authentication & Authorization: Keystone #

Keystone is the project for the OpenStack Identity service that takes care of authenticating users by requiring them to log in to the API services and the Graphic User Interface (GUI) with a combination of a user name and a password. Keystone then determines what role a specific user has inside a project (or tenant). All OpenStack components associate certain roles with certain permissions. If a user has a certain role in a project, that automatically entitles them to the permissions of said role for every respective service.

Keystone is one of the few services that only comprises of one program, the Keystone API itself. It is capable of connecting to existing user directories such as LDAP or Active Directory but can also run in a stand-alone manner.

2.3.5 Operating System Image Provisioning: Glance #

Glance is the project for the OpenStack Image service that stores and administers operating system images.

Not all customers consuming cloud services are IT professionals. They may not have the knowledge required to install an operating system in a newly created virtual machine (VM) in the cloud. And even IT professionals who are using cloud services cannot go through the entire setup process for every new VM they need to create. That would take too much time and hurt the principle of the economy of scale. But it also would be unnecessary. A virtual machine inside KVM can, if spawned in a cloud environment, can be very well controlled and is the same inside different clouds if the underlying technology is identical. It has hence become quite common for cloud provider to supply users with a set of basic operating system images compatible with a given cloud.

2.3.6 Virtual Networking: Neutron #

Neutron is the project for the OpenStack Networking service that implements Software Defined Networking (SDN).

Networking is a part of modern-day clouds that shows the most obvious differences to conventional setups. Most paradigms about networking that are valid for legacy installations are not true in clouds and often not even applicable. While legacy setups use technologies such as VLAN on the hardware level, clouds use SDN and create a virtual overlay networking level where virtual customer networks reside. Customers can design their own virtual network topology according to their needs, without any interaction by the cloud provider.

Through a system of loadable plug-ins, Neutron supports a large number of SDN implementations such as Open vSwitch. Chapter 3 elaborates on networking in OpenStack and Neutron in deep detail. It explains how networks for clouds must be designed to accommodate for the requirements of large-scale cloud implementations.

2.3.7 Persistent VM Block-Storage: Cinder #

Cinder is the project for the OpenStack Block Storage service that takes care of splitting storage into small pieces and making it available to VMs throughout the cloud.

Conventional setups often have a central storage appliance such as a SAN to provide storage to virtual machines through the installation. These devices come with several shortcomings and do not scale the way it is required on large-scale environments. And no matter what storage solution is in place, there still needs to be a method to semi-automatically configure the storage from within the cloud to create new volumes dynamically. After all, giving administrative rights to all users in the cloud is not recommended.

Chapter 4 elaborates on Cinder and explains in deep detail how it can be used together with the Ceph object store to provide the required storage in a scalable manner in cloud environments.

2.3.8 Compute: Nova #

Nova is the project for the OpenStack Compute service that is the centralized administration of compute resources and virtual machines. Nova was originally developed by the Nebula project at NASA and from which most other projects have spawned off.

Whenever a request to start a new VM, terminate an existing VM or change a VM is issued by a user, that request hits the Nova API component first. Nova is built of almost a dozen different pieces taking care of individual tasks inside a setup. That includes tasks such as the scheduling of new VMs the most effective way (that is, answering the question "What host can and should this virtual machine be running on?") and making sure that accessing the virtual KVM console of a VM is possible.

Nova is a feature-rich component: Besides the standard hypervisor KVM, it also supports solutions such as Xen, Hyper-V by Microsoft or VMware. It has many functions that control Nova’s behavior and is one of the most mature OpenStack components.

2.3.9 A Concise GUI: Horizon #

Horizon is the project for the OpenStack Dashboard service that is the standard UI interface of OpenStack and allows concise graphical access to all aforementioned components.

OpenStack users may rarely ever use Horizon. Clouds function on the principle of API interfaces that commands can be sent to in a specialized format to trigger a certain action, meaning that all components in OpenStack come with an API component that accepts commands based on the RESTful HTTP approach.

There are, however, some tasks where a graphical representation of the tasks at hand is helpful and maybe even desired. Horizon is written in Django (a Python-based HTML version) and must be combined with a WSGI server.

2.4 A Perfect Design for OpenStack #

To put it into a metaphor: OpenStack is like an orchestra where a whole lot of instruments need to join forces to play a symphony. That is even more true for large environments with huge numbers of participating nodes. What is a good way to structure and design such a setup? How can companies provide a platform suitable for the respective requirements in the best and most resilient manner? The following paragraphs answer these questions.

2.4.1 Logical layers in Cloud environments #

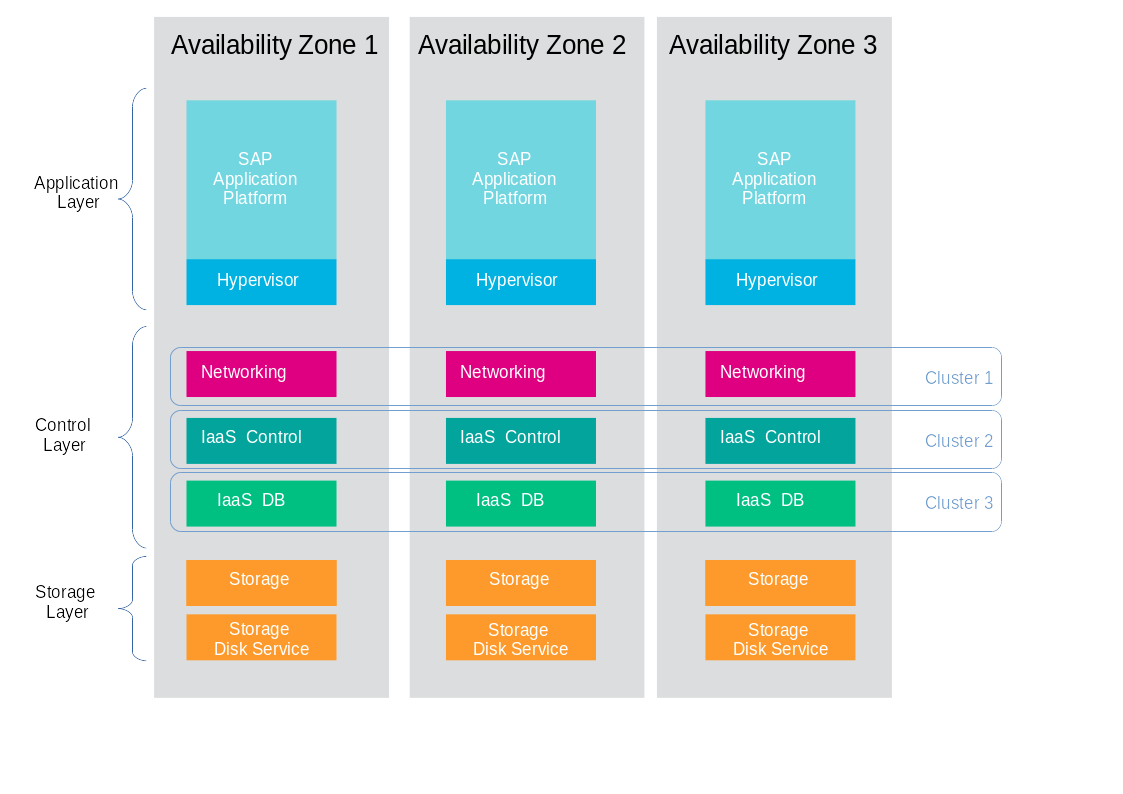

To understand how to run a resilient and stable cloud environment, it is important to understand that a cloud comes with several layers. These layers are:

The hardware layer: This layer contains all standard rack servers in an environment, this means devices that are not specific network devices or other devices such as storage appliances.

The network layer: This layer contains all devices responsible for providing physical network connectivity inside the setup and to the outside. Switches, network cabling, upstream routers, and special devices such as VPN bridges are good examples.

The storage layer: This layer represents all devices responsible for providing persistent storage inside the setup along with the software components required for that. If solutions such as Ceph are in use, the storage layer only represents the software required for SDN as the hardware is already part of the hardware layer.

The control layer: This layer includes all logical components that belong to the cloud solution. All tools and programs in this layer are required for proper functionality of the system.

The compute layer: This layer covers all software components on the compute nodes of a cloud environment.

A cloud can encounter different scenarios of issues that come with different severities. The two most notables categories of issues are:

Loss of control: In such a scenario, existing services in the cloud continue to work as before, but it is impossible to control them via the APIs provided by the cloud. It is also impossible to start new services or to delete existing services.

Loss of functionality: Here, not only is it impossible to control and steer the resources in a cloud but instead, these resources have become unavailable because of an outage.

When designing resilience and redundancy for large-scale environments, it is very important to understand these different issue categories and to understand how to avoid them.

2.4.2 Brazing for Impact: Failure Domains #

An often discussed topic is the question of how to make a cloud environment resilient and highly available. It is very important to understand that "high availability" in the cloud context is usually not the same as high availability in the classical meaning of IT. Most administrators used to traditional IT setups typically assume that the meaning for high availability for clouds is to make every host in the cloud environment redundant. That is, however, usually not the case. Cloud environments make a few assumptions on the applications running inside of them. One assumption is that virtual setups are as automated as possible. That way, it is very easy to restart a virtual environment in case the old instance went down. Another assumption that applications running there are cloud-native and inherently resilient against failures of the hardware that they reside on.

Most major public cloud providers have created SLAs that sound radical from the point of view of conventional setups. Large public clouds are often distributed over several physical sites that providers call regions. The SLAs of such setups usually contain a statement according to which the cloud status is up. If a cloud is up, it means that customers can in any region of a setup start a virtual machine that is connected to a virtual network.

It must clearly be stated in the SLA that the provider of a cloud setup has no guarantee of the availability of all hosts in a cloud setup at any time.

The focus of availability is on the control services, which are needed to run or operate the cloud itself. OpenStack services have a stateless design and can be easily run in an active/active manner, distributed on several nodes. A cluster tool like Pacemaker can be used to manage the services and a load balancer in front of all and can combine the services and make them available for the users. Any workload running inside the cloud cannot be taken into account. With the feature compute HA, SUSE OpenStack offers an exception. However, it should be used only where it is required, because it adds complexity to the environment and makes it harder to maintain. It is recommended to create a dedicated zone of compute nodes, which provide the high availability feature.

In all scenarios, it makes sense to define failure domains and to ensure redundancy over these. Failure domains are often referred to as availability zones. They are similar to the aforementioned regions but usually cover a much smaller geological area.

The main idea behind a failure domain is to include every needed service into one zone. Redundancy is created by adding multiple failure domains to the design. The setup needs to make sure that a failure inside of a failure domain does not affect any service in any other failure domain. In addition, the function of the failed service must be taken over by another failure domain.

It is important that every failure domain is isolated with regard to infrastructure like power, networking, and cooling. All services (control, compute, networking and storage) need to be distributed over all failure domains. The sizing needs to take into account that even if one complete failure domain dies, enough resources need to be available to operate the cloud.

The application layer is responsible for distributing the workload over all failure domains, so that the availability of the application is ensured in case of a failure inside of one failure domain. OpenStack offers anti-affinity rules to schedule instances in different zones.

The minimum recommended amount of failure domains for large scale-out setups based on OpenStack is three. With three failure domains in place, a failure domain’s outage can easily be compensated by the remaining two. When planning for additional failure domains, it is important to keep in mind how quorum works: To have quorum, the remaining parts of a setup must have the majority of relevant nodes inside of them. For example, with three failure domains, two failure domains would still have the majority of relevant nodes in case one failure domain goes down. The majority here is defined as "50% + one full instance".

2.4.3 The Control Layer #

The control layer covers all components that ensure functionality and the ability to control the cloud. All components of this layer must be present and distributed evenly across the available failure domains, namely:

MariaDB: An instance of MariaDB should be running in every failure domain of the setup. As MariaDB clustering does not support a multi-master scenario out of the box, the Galera clustering solution can be used to ensure that all MariaDB nodes in all failure domains are fully functional MariaDB instances, allowing for write and read access. All three MariaDB instances form one database cluster in a scenario with three availability zones. If one zone fails, the other two MariaDB instances still function.

RabbitMQ: RabbitMQ instances should also be present in all failure domains of the installation. The built-in clustering functionality of RabbitMQ can be used to achieve this goal and to create a RabbitMQ cluster that resembles the MariaDB cluster described before.

Load balancing: All OpenStack services that users and other components themselves are using are HTTP(S) interfaces based on the REST principle. In large environments, they are subject to a lot of load. In large-scale setups, it is required to use load balancers in front of the API instances to distribute the incoming requests evenly. This holds also true for MySQL (RabbitMQ however has a built-in cluster functionality and is an exception from the rule).

OpenStack services: All OpenStack components and the programs that belong to them with the exception of

nova-computeandneutron-l3-agentwhich must be running on dedicated hosts (controller nodes) in all failure domains. Powerful machines are used to run these on the same hosts together with MariaDB and RabbitMQ. As OpenStack is made for scale-out scenarios, there is no issue resulting from running these components many times simultaneously.

2.4.4 The Network Layer #

The physical network is expected to be built so that it interconnects

the different failure domains of the setup and all nodes redundantly. The

external uplink is also required to be redundant. A separate node in

every failure domain should act as a network node for Neutron.

A network node ensures the cloud’s external connectivity by running

the neutron-l3-agent API extension of Neutron.

In many setups, the dedicated network nodes also run the DHCP agent for Open vSwitch. Note that this is a possible and a valid configuration but not under all circumstances necessary.

OpenStack enriches the existing Open vSwitch functionality with a feature usually called Distributed Virtual Routing (DVR). In setups using DVR, external network connectivity is moved from the dedicated network nodes to the compute node. Each compute node runs a routing service, which are needed by the local instances. This helps in two cases:

Scale-out: Adding new compute nodes also adds new network capabilities.

Failure: A failure of a compute node only effects the routing of local instances.

The routing service is independent from the central networking nodes.

Further details on the individual components of the networking layer and the way OpenStack deals with networking are available in chapter 3 of this document.

2.4.5 The Storage Layer #

Storage is a complex topic in large-scale environments. Chapter 4 deals with all relevant aspects of it and explains how a Software Defined Storage (SDS) solution such as Ceph can easily satisfy a scalable setup’s need for redundant storage.

When using an SDS solution, the components must be distributed across all failure domains so that every domain has a working storage cluster. Three nodes per domain are the bare minimum. In the example of Ceph, the CRUSH hashing algorithm must also be configured so that it stores replicas of all data in all failure domains for every write process.

Should the Ceph Object Gateway be in use to provide for S3/Swift storage via a RESTful interface, that service must be evenly available in all failure domains as well. It is necessary to include these servers in the loadbalancer setup that is in place for making the API services redundant and resilient.

2.4.6 The Compute Layer #

When designing a scalable OpenStack Setup, the Compute layer plays an important role. While for the control services no massive scaling is expected, the compute layer is mostly effected by the ongoing request of more resources.

The most important factor is to scale-out the failure domains equally. When the setup is extended, comparable amounts of nodes should be added to all failure domains to ensure that the setup remains balanced.

When acquiring hardware for the compute layer, there is one factor that many administrators do not consider although they should: the required ratio of RAM and CPU cores for the expected workload. To explain the relevance of this, think of this example: If a server has 256 gigabytes of RAM and 16 CPU cores that split into 32 threads with hyper-threading enabled, a possible RAM-CPU-ratio for the host is 32 VMs with one vCPU and 8 gigabytes of RAM. One could also create 16 VMs with 16 gigabytes and two vCPUs or 8 VMs with 32 gigabytes of RAM and 4 vCPUs. The latter is a fairly common virtual hardware layout (this is called a flavor) example for a general purpose VM in cloud environments.

Some workloads may be CPU-intense without the need for much RAM or may require lots of RAM but hardly CPU power. In those cases, users would likely want to use different flavors such as 4 CPU cores and 256 Gigabytes of RAM or 16 CPU cores and 16 gigabytes of RAM. The issue with those is that if one VM with 4 CPU cores but 256 gigabytes of RAM or 16 CPU cores and 16 gigabytes of RAM runs on a server, the remaining resources on said machine are hardly useful for any other task as they blend together and may remain unused completely.

Cloud providers need to consider the workload of a future setup in the best possible way and plan compute nodes according to these requirements. If the setup to be created is a public cloud, pre-defined flavors should indicate to customers to the desired patterns of usage. If customers do insist on particular flavors, the cloud provider must take the hardware that remains unused in their calculation. If the usage pattern is hard to predict, a mixture of different hardware kinds likely make the most sense. It should be noted that from the operational point of view, the same hardware class is used. This helps to reduce the effort in maintenance and spare parts.

OpenStack comes with several functions such as host aggregates to make maintaining such platforms convenient and easy. The ratio of CPU and RAM is generally considered 1:4 in the following examples.

2.5 Reference Architecture #

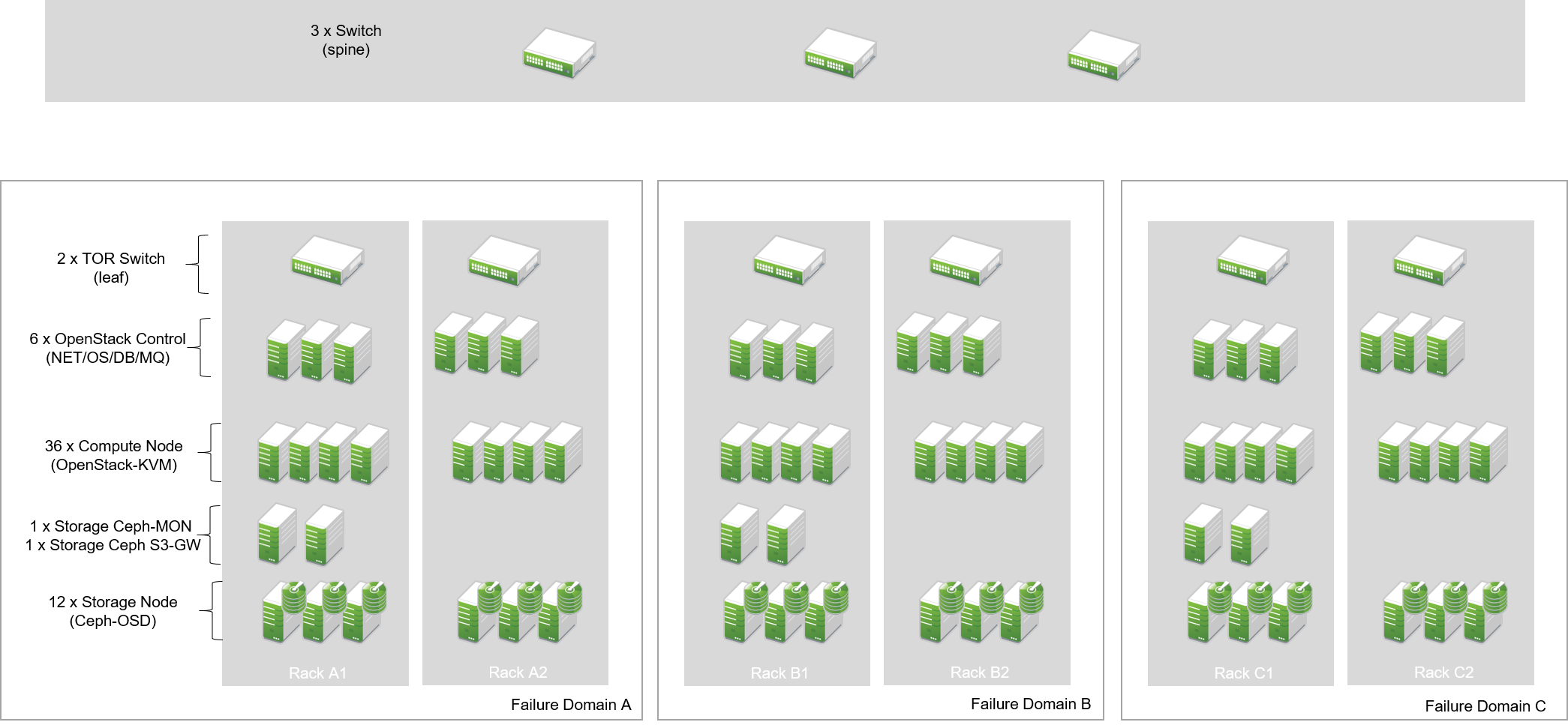

The following paragraphs describe a basic design reference architecture for a large-scale SUSE OpenStack Cloud based on OpenStack and Ceph.

2.5.1 Basic Requirements #

To build a basic setup for a large-scale cloud with SUSE components, the following criteria must be fulfilled:

Three failure domains (at least in different fire protection zones in the same datacenter, although different datacenters would be better) that are connected redundantly and independently from each other to power and networking must be available.

OSI level 2 network hardware, spawning over the three failure domains to ensure connectivity. For reasons of latency and timing, the maximum distance between the three failure domains should not exceed ten kilometers.

SUSE OpenStack Cloud must be deployed across all failure domains.

SUSE Enterprise Storage must be deployed across all failure domains.

SUSE Manager or a Subscription Management Tool (SMT) instance must be installed to mirror all the required software repositories (including all software channels and patches). This provides the setup with the latest features, enhancements, and security patches.

Adequate system management tools (as explained in chapter 5) must be in place and working to guarantee efficient maintainability and to ensure compliance and consistency.

2.5.2 SUSE OpenStack Cloud roles #

SUSE OpenStack Cloud functions based on roles. By assigning a host a certain role, it automatically also has certain software and tasks installed and assigned to it. Four major roles exist:

Administration Server: The administration server contains the deployment nodes for SUSE OpenStack Cloud and SUSE Enterprise Storage. It is fundamental to the deployment and management of all nodes and services as it hosts the required tools. The administration servers can also be a KVM virtual machine. The administration services do not need to be redundant. A working backup and restore process is sufficient to ensure the operation. The virtualization of the nodes makes it easy to create snapshots and use them as a backup scenario.

Controller Node Clusters: These run the control layers of the cloud. SUSE OpenStack Cloud can distribute several OpenStack services onto as many servers as the administrator sees fit. There must be one Controller Node Cluster per failure domain.

Compute Nodes: As many compute nodes as necessary must be present; how many depends on the expected workload. All compute nodes must be distributed over the different failure domains.

Storage Nodes: Every failure domain must have a storage available. This example assumes that SUSE Enterprise Storage is used for this purpose. The minimum required number of storage nodes per failure domain is 3.

Management Nodes: To run additional services such as Prometheus (a time-series database for monitoring, alerting and trending) and the ELK stack (Elasticsearch, Logstash, Kibana - a log collection and index engine), further hardware is required. At least three machines per failure domain should be made available for this purpose.

Load Balancers: In the central network that uplinks to the setup, a load balancer must be installed — this can either be an appliance or a Linux server running Nginx, HAProxy, or other load balancing software. The load balancer must be configured in a highly available manner as loss of functionality on this level of the setup would make the complete setup unreachable.

The following picture shows a minimal implementation of this reference architecture for large-scale cloud environments. It is the ideal start for a Proof of Concept (PoC) setup or a test environment. For the final setup, remember to have dedicated control clusters in all failure domains. Note that this is in contrast to what the diagram shows.

2.6 SUSE OpenStack Cloud and SUSE Enterprise Storage #

The basic services of an IaaS Cloud offers Compute, Networking, and Storage services. SUSE OpenStack Cloud is the base for the Compute and Networking services. For the storage, it is recommended to use a software defined solution and in most cases, a Ceph-based solution is used. SUSE Enterprise Storage is such a Ceph-based distribution and fits perfectly to SUSE OpenStack Cloud.

Both products team up perfectly to build a large-scale OpenStack platform. Certain basic design tenets such as the distribution over multiple failure domains are integral design aspects of these solutions and implicitly included. Both products not only help you to set up OpenStack but also to run it in an effective and efficient way.

3 Networking #

Cloud environments and large-scale clouds come with requirements for physical and virtual networking that are fundamentally different from conventional setups. This chapter compares in detail network requirements in conventional setups and large-scale clouds and elaborates on the major differences. It shows how Software Defined Networking (SDN) is used to provide scalable and reliable networking for large-scale clouds and what technologies are available in OpenStack to implement proper SDN.

3.1 Networking in Conventional Setups #

For a modern computing installation in a data center, networking is as important as other services and components, such as storage or the compute facilities. Conventional setups share several design aspects for networking and have similarities in how networking adds to the overall value of the setup.

3.1.1 Cloud Computing Versus Conventional Setups #

Three design aspects are typical for networking in conventional setups:

No need for scalability: In conventional setups, the maximum size of the setup is determined from the start of the project. Networking capabilities, such as the overall required amount of switch ports, can be planned right in the beginning. This ensures the capabilities are sufficient for the largest size the setup can scale to. Scalability is not a typical design requirement in conventional setups, giving the network a very static look and feel. Conventional setups also do not grow to sizes that cannot be handled using COTS networking hardware. Even if several hundreds of ports are required, standard 48-port switches work well and allow for a standard tree or star-based network layout.

Individual networks for individual customers: Conventional setups are planned per customer. As a consequence, the network infrastructure that is specific for a certain setup belongs to that customer and is not shared with other customers. This means multi-tenancy is not a design tenet of networking in conventional setups. Additionally, in conventional setups, network maintenance is provided by the ISP for the customer. This gives the ISP the full control over all configuration aspects of the network.

VLANs and other switch features are used: In setups where clients that belong to different customers share common networking segments, the management functionalities of switches are extensively used. One example are VLANs. This is a technology to logically shield traffic from other traffic on a switch, which must be configured in the management interface of each particular network device that is supposed to know about them.

The following explains why network design tenets of conventional setups do not work well in cloud computing environments:

Need for scalability: It is impossible to predict the final size of a cloud computing environment right from the start. The setup can consist of hundreds or thousands of nodes that all need to be able to communicate properly with each other. OpenStack is designed for seamless and almost unlimited growth of the cloud platform. The networking infrastructure in place must be able to cope with this scalability. This affects the physical and the logical setup. Star of tree-based layouts may not work well for clouds because they limit the available bandwidth to individual ports. In addition, the logical separation into VLANs can become a problem because a setup may run out of VLAN IDs.

Individual configuration and shared network segments everywhere: To reach the target of seamless and limitless scalability, clouds do not dedicate specific hardware to individual customers. All network elements and segments are shared amongst all customers in the setup, making it impossible to establish customer-specific setups and configurations on individual devices. Every attempt to do so violates the principle of scalability, which makes this approach in clouds impossible to follow. In contrast, users must have the ability to determine the topology of their virtual networks completely at their own discretion. The cloud solution in place must ensure that the desired configuration is implemented physically and logically in a safe manner and independently from other customers.

No customer specific configuration on hardware: Individual switches must not contain user-specific configuration data. This would not only violate the principle of scalability, but also make it impossible for customers to service themselves when becoming a new customer in a cloud computing environment. However, the ability to serve themselves is a major difference when it comes to clouds and conventional setups. User-specific settings on switches and other network devices can only be enabled using an administrator account. A cloud provider though does not want to give administrator access to all networking devices to all customers in their cloud. As a consequence, features such as VLANs that require network hardware reconfiguration cannot be used in clouds. However, the functionality they provide is still required.

3.2 Networking in Cloud Environments #

To understand how functionality provided by network devices in conventional setups can be provided in cloud environments, it is important to understand how modern switches work. They are built up of three major components:

Data plane: The data plane is the component of a switch that forwards packets from one of its ports to another. It does not perform any qualification of traffic but simply forwards and redirects packets according to the original requests.

Control plane: The control plane performs packet qualification and establishes the policies required for features such as VLANs. It holds all rule sets configured by the author and influences the forwarding of packets in the data plane.

Management plane: The management plane provides all the functions used to control and monitor networking devices. For the purpose of this document, it is considered a subset of the control plane and not mentioned separately.

3.2.1 Special Requirements in Clouds #

In cloud environments, the control plane of networking devices cannot be used in the same ways as in conventional setups. The reason is that this would break the principle of scalability and the users' ability to service themselves in using cloud resources. The features provided by control planes, such as the segregation of traffic belonging to different customers are also necessary in cloud environments and must be present.

To combine the best of both worlds, cloud setups use a concept that is referred to as decoupling: The data plane functionality of switches is retained and used, while the control plane functionality is moved from individual switches onto a software layer that can be centrally configured from within a cloud computing environment. As the control plane functionality is implemented in standard software after the decoupling has taken place, such setups are called Software Defined Networking.

3.3 Software Defined Networking Primer #

Like conventional network setups, setups leveraging SDN functionality split into multiple physical and logical layers. The most important layer is the physical layer representing the data plane. Without this functionality, networks inside clouds or in any other kind of setup would not work. The important difference between conventional setups and SDN-based setups is that in SDN-based setups, the data plane of switches is the only actively used core functionality. Switches in clouds only forward packets from one port to another. Their built-in control plane is unused.

In SDN-based setups, a new, virtual control plane is established as a central and integral component of the cloud computing setup. This comes with advantages; functionality decentrally provided by individual switches in standard setups is now provided by a single, central instance holding valid configuration data for the entire environment. Being an integral part of the cloud, the control plane configuration can be edited directly in the cloud software without the need to log in to individual network devices and change their local configuration.

The control plane of individual switches is replaced with many virtual control planes (this means virtual switches) present on every single host that is part of the setup. As all hosts receive their configuration from the same central configuration database, the correct setup for each particular host is applied directly there. Functionality that would be provided by the control plane of network switches is provided by combining several logical technologies directly on the hosts.

This layout comes with one main advantage: Customers running services and VMs in the cloud have the option to design the network topology in their area of the cloud completely at their will. They are free to implement any network configuration. And they control the configuration of their virtual networks using the same Cloud APIs that they use to control all other services. As customer networks in clouds are virtual networks and shielded from each other, they cannot accidentally collide with each other. It also is impossible for attackers to sniff traffic from other networks.

3.3.1 Basic Design Tenets of SDN Environments #

To understand how SDN in cloud environments works down to the individual port of a switch that a server is connected to, it is important to know that cloud setups distinguish between different kinds of network traffic.

Management traffic: This traffic type is used by the components of the cloud software such as OpenStack to communicate with each other. As cloud solutions are built in a modular manner, different components need to talk to each other. Usually a cloud environment has a management network that serves exactly this purpose. The management network is also called underlay network. Virtual machines running in the cloud by different customers are logically split from this network and do not have direct access to it.

Customer traffic: This traffic type denotes the payload traffic produced by paying customers in the cloud. As the networks used for this kind of traffic in clouds do not physically exist (in the form of a VLAN configuration on some network device), these networks are referred to as virtual. Traffic floating in these virtual networks splits into two different sub-types: Internal traffic is traffic inside a virtual network, it remains in the network but may cross host borders (for example the traffic from two VMs in the same virtual network running on different hosts). In contrast to that, external traffic is traffic coming from a virtual network and targeting a different network, either in the same cloud or in the Internet. As this network layer uses the underlay for the physical exchange of data, it is called overlay.

3.3.2 Encapsulation in SDN Environments #

At a certain point in time, even the traffic passing between virtual machines in virtual networks must cross the physical borders between two systems. Virtual traffic usually uses the management network, but to ensure that management traffic of the platform and traffic from virtual networks do not mix up, all available SDN solutions use some sort of encapsulation. VXLAN and GRE tunnels are the most common choices (both terms refer to specific technologies). Both technologies allow for the assignment of certain IT tags to individual network packets. Traffic can easily be identified as originating from a specific network.

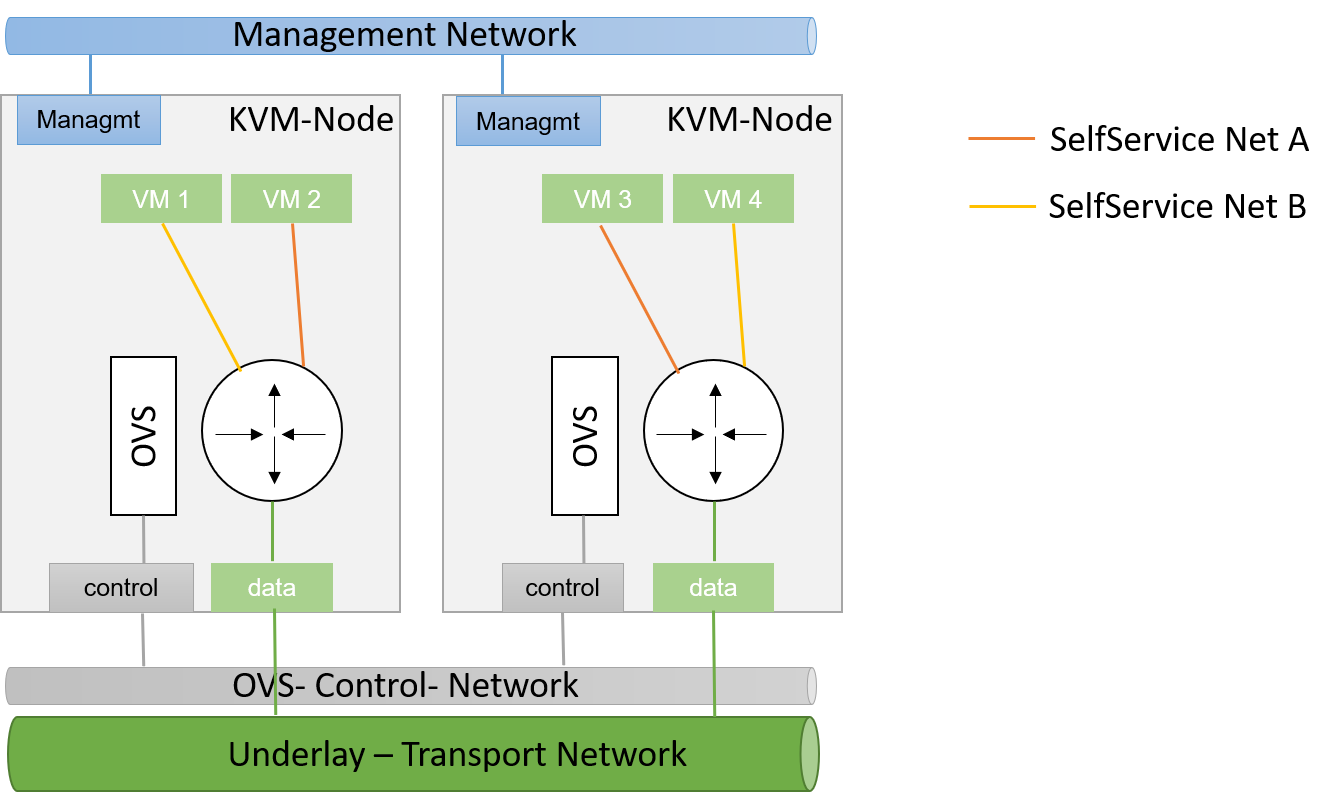

On hosts with SDN setups, software such as Open vSwitch is employed to create a virtual local switch that can handle the virtual networking IDs. Virtual machines that are started on a host and associated with a specific virtual network by user request have a direct connection to the virtual switch on the host. That way, the virtual switch on the source host and the virtual switch on the target host can reliably identify the virtual network that said traffic belongs to and only forward the packets to virtual ports on the virtual switches authorized to see it. This principle re-implements the VLAN functionality of conventional switches in virtual networks in the cloud and ensures the true separation of traffic between customers and even virtual networks within the same customer environment. In contrast to conventional setups, the settings can be modified from within the cloud environment directly. Logging in to the management interfaces of switches is no longer necessary.

3.3.3 Local Traffic in SDN Environments #

When encapsulation is set up on the host level, newly started VMs are automatically connected to virtual networks if the VM spawn request contains according instructions. When the VM has a working IP address, it can communicate with other VMs in the same virtual network.

One characteristic of cloud environments is to not use static local IP addresses in virtual networks. Instead, cloud VMs are expected to use DHCP to acquire their local IP address at boot time. The cloud solution in turn is responsible for running a DHCP server that assigns a pre-determined IP to a cloud VM when the according DHCP request is received. The cloud software also takes care of IP address management (IPAM) of local IPs. This is the source for IP information in the DHCP server run by the cloud environment.

3.3.4 External Traffic in SDN Environments #

The ability to exchange traffic securely between virtual machines inside a cloud is important, but just as important is the ability to communicate with the outer world. To ensure this works, there needs to be a device operating as gateway between the virtual networks and external networks. All currently available cloud solutions support such a functionality. Usually the hosts assuring the traffic flow are called gateway nodes or networking nodes. Networking nodes do not need to be distinct servers. The role of gateway nodes can also be assigned to other existing machines. Gateway nodes are shared networking components; they have connections to a physical network and many virtual networks. As they use the same encapsulation technology as compute nodes when VMs exchange traffic, data separation on network nodes is ensured.

Internet nodes also ensure that individual VMs run by customers can be directly reached from the Internet. The static assignment of external IPs to individual VMs does not work in clouds. This approach would not only break the principle of scalability, it would also break the idea of the consumption-based payment model of most clouds, and the principle of the customers to service themselves properly. Instead of statically assigning external IPs to virtual machines, customers must have the ability to decide at any point in time whether one of their VMs requires an external IP address or not. To reach this goal, IP addresses must be managed by the cloud platform itself. Most clouds do that by combining several technologies available in the Linux kernel to map an official IP address to the local IP of a VM in the cloud (Floating-IP).

3.3.5 SDN Summary #

SDN is of crucial importance in cloud setups. It ensures you do not need to rely on static configuration facilities. By turning switches into mere packet-forwarding devices and moving the control facility into the cloud, SDN allows you to create truly integrated multi-tenant setups featuring all functions expected in modern setups.

Several SDN implementations are available on the market and considered production ready. The most prominent one is Open vSwitch. Many solutions such as Midonet by Midokura are based on Open vSwitch. Others are independent developments such as the Tungsten Fabric distribution owned by Juniper.

3.4 Software Defined Networking in OpenStack #

OpenStack leverages the advantages of SDN. SDN functionality is provided by neutron, the Networking service of OpenStack.

3.4.1 Neutron Primer #

Neutron is a service that offers a RESTful API and a plugin mechanism that allows to load plugins for a large number of SDN implementations. In certain setups, SDN solutions can be combined. However, combining SDN solutions is a complex task and should be accompanied by expert support.

In neutron, many plugins to enable certain SDN implementations are available. The standard solution is Open vSwitch which can be easily combined with neutron and is well supported by SUSE OpenStack Cloud. Other neutron plug-ins exist for solutions such as Tungsten Fabric or Midonet by Midokura. Some commercial SDN implementations can also be combined with SUSE OpenStack Cloud.

For the purpose of this document is it assumed that Open vSwitch-based SDN is used.

Like all OpenStack components, neutron has a decentralized design. This is necessary as the correct functioning of SDN in an OpenStack cloud requires multiple components on different target systems to work together properly. As an example, when a host boots up, the virtual switch for SDN on it must be configured at boot time. When a new VM is started on said host, a virtual port on the local virtual switch must be created and tagged with the correct settings for VXLAN or GRE. The VM needs the network information (IP, DNS, Routing) and additional metadata to configure itself.

OpenStack neutron follows an agent-based architecture. Beside a central API service, which is running on the control nodes, several L2 and L3 agents are running on the network or compute nodes.

3.4.2 SDN Architecture in OpenStack Clouds #

Building SDN for OpenStack environments follows the basic design tenets laid out earlier in this chapter. A typical SDN environment deployed as part of SUSE OpenStack Cloud uses Open vSwitch to create the virtual or overlay network segment and VXLAN or GRE encapsulation to encapsulate traffic on the underlay level of the physical network, acting as management network.

As Open vSwitch is the default SDN solution for neutron, SUSE OpenStack Cloud guarantees and leverages an efficient integration between neutron and Open vSwitch.

When combining OpenStack and Open vSwitch, networking functionality in large-scale environments is split across several nodes. Several networking nodes must be available and connected to a powerful upstream link. The minimum number of networking nodes is three but may be much higher depending on the setup’s load. The upstream link is used to accommodate the environment’s traffic needs and should include a buffer to guarantee the option to upgrade the link at a later point in time.

API services should run behind a load balancer to accommodate for high amounts of incoming requests. It is recommended to have at least three load balancers.

All networking nodes should be running an instance of the neutron DHCP agent to ensure that the customer’s VMs receive replies to their DHCP requests.

The SUSE OpenStack Cloud offering comes pre-equipped for this SDN setup and enables the facilitation of such configurations.

3.4.3 OpenStack SDN Summary #

The combination of Open vSwitch and OpenStack neutron provides a well-functioning implementation of SDN in a cloud computing environment. Open vSwitch has been improved recently, making it more stable and resilient than it used to be a few years ago. Customers starting to look into OpenStack are recommended to test the Open vSwitch approach first before resorting to other solutions.

However, depending on the setup, Open vSwitch may not be the best fit for that respective setup. One weak point in the Open vSwitch design is that Open vSwitch does not have a central location for all virtual networks and virtual machines in the setup.

While this technical approach is not an issue in medium-sized environments, it can become a problem in large clouds because of the overhead traffic generated by virtual machines trying to find each other. Standard protocols such as ARP come into use for this purpose and generate a lot of additional traffic in Open vSwitch setups.

If Open vSwitch is not the best SDN solution for a given use case, there are several alternatives available. Most of the alternatives based on Open vSwitch avoid the issues described above by extending Open vSwitch with a central location for network and VM information.

Using Open vSwitch traffic flows in these setups, traffic is manipulated to ensure overhead traffic is avoided. A solution that uses such manipulation strategies helps to reduce the SDN-induced overhead. Other solutions such as Tungsten Fabric follow design principles that are fundamentally different from Open vSwitch.

Finding the right SDN implementation involves proper planning and depends on the requirements on-site. Trusting a proven solution helps to proceed faster and build a resilient setup. With Open vSwitch, OpenStack provides a scalable and proven implementation, which can create a large scale-out architecture.

3.5 Physical Networks in Large-Scale Environments #

Conventional network designs such as star or tree-based approaches are not an ideal solution for scale-out environments. This is because the highest switch level is congested at some point and it is not possible to connect additional switches to the highest level of the switching hierarchy. High availability on the physical level is a concern too. Every server consumes two network ports on the local network infrastructure to connect to two separate switches. This further increases the amount of required ports and switch interconnects.

Such issues can be worked around at the cost of making the setup more expensive and complex. One approach is Layer-3 routing: In such a scenario, the Internet routing protocol BGP is used for routing traffic even between the local nodes of the installation. Every node turns into a small router that knows the exact network paths to all other servers. The advantage of such setups is that logical borders of individual networks no longer matter. At any time, the network can be extended by new switches plugged in anywhere in the setup. If the highest level of such leaf-spine architectures has no port available for new switches, a new and higher level of additional core switches can be installed at any time thanks to BGP.

While SDN is necessary on the level of networking inside cloud environments, ISPs setting up a cloud need to carefully decide whether they want to run a platform with 200 to 600 hosts or more. Only considerably high target node numbers justify a layer-3-based setup as explained. In addition, such BGP-based setups are very specific to a customer’s setup and cannot be implemented using standard tools and products. Request expert support at an early stage to ensure the SDN implementation does not put your entire project at risk.

4 Storage #

A working implementation for the storage of customer payload data is crucially important to any setup present in modern IT. This chapter elaborates on the relevance of storage and a typical implementation in conventional setups. It explains how storage requirements are different in scalable platforms and clouds and why conventional approaches are not suitable. Finally, it details what object storage is, how Ceph works and how SUSE Enterprise Storage based on Ceph is an ideal storage solution for highly scalable environments such as OpenStack.